A rainstorm—a real gully washer—hits the Northwest. In numerous cities with antiquated public plumbing, the rain seeps into cracked sewage lines and flows into stormwater drains that link to the sewer system. From Port Angeles to Seattle to Spokane, treatment plants are overwhelmed by the deluge, causing raw sewage to spill into Port Angeles Harbor, Puget Sound, and the Spokane River. The sewage carries bacteria, viruses, and other pollutants that pose a risk to beach goers hunting clams or swimmers taking a dip.

Spewing sewage into waterways is potentially dangerous to people, and just plain gross. So Seattle and King County alone are preparing to spend $1.3 billion on projects to fix the problem. The navy town of Bremerton on Puget Sound’s west shore recently finished a project costing more than $50 million to staunch the annual flow of hundreds of millions of gallons of sewage-tainted waste. Outside of the state, Vancouver, BC, is working to separate its sewage system and Portland this year is scheduled to complete its $1.4 billion Big Pipe projects to control sewage spills.

But there’s increasing concern that the regulations driving these costly fixes are based on an arbitrary benchmark. A recent article that I wrote for Crosscut and last Sunday’s piece by Lynda Mapes at the Seattle Times both called into question the sewage rule and the priority being placed on shrinking the number of combined-sewer overflows (CSOs) at a time when the region faces arguably more urgent water-quality challenges.

Washington’s leaders need to reconsider a rule that limits the number of sewage overflows to an average of one per outfall. Instead, they need to craft rules grounded in the actual harm being caused by the spill by considering how much and what kind of pollution is being dumped. By focusing the regulation on the environmental and human health effects, cities, counties, and utility rate payers will be able to direct their time and money to projects that will have the greatest benefits to the region. Reshaping the CSO rules could save money by shifting restoration dollars to projects that pay the largest dividends.

As Mapes explained in her story (emphasis mine):

As Mapes explained in her story (emphasis mine):

… (S)urface runoff, not CSO discharge, is the single largest source of pollution to Puget Sound, according to the Puget Sound Partnership, the state agency charged with cleaning up and restoring Puget Sound, and the state Department of Ecology. Carrying contaminants such as copper, zinc, oil, lawn fertilizers and animal waste, surface runoff barrels untreated from storm drains all over (Seattle) into Puget Sound, not just in heavy storms but nearly every time it rains.

…Today, in the partnership’s Action Agenda for Puget Sound, CSOs don’t rank in the top 10 or even the top 20 things to do to reduce water pollution in Puget Sound.

One spill limit

Seattle and King County already have made costly investments that dramatically reduced the amount of sewage being spilled via CSOs, but to reach state standards, much more work is needed.

Washington rules require no more than one overflow on average from each outfall. Ecology, which regulates these outfalls, can choose to average the number of spills over 10 or even 20 years, making it easier to clear the legal bar. The rules, which date to 1987, precede US regulations for CSOs, which came out in 1994.

As Larry Altose, Ecology spokesman, defended the policy to me:

“(Washington’s) system is actually quite flexible, and protective of human health and the environment.”

Dennis McLerran, the head of the EPA for region 10, which includes Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska, came to the defense of local CSO efforts in response to the Seattle Times story. In a written statement he explained:

Combined systems — and climates like Seattle’s — often conspire to produce huge sewage and storm water overflows during the wet winter months. It’s our view that there are few better investments than protecting our citizens and waterways, especially Puget Sound, from millions of gallons of raw sewage.

I’ll agree that fixing combined systems is a great way to get sewage out of waterways, but is sewage worthy of the attention that it’s getting relative to other pollutants, particularly the toxic mix that’s carried with stormwater runoff?

Some folks, including Chris Wilke, executive director of the Puget Soundkeeper Alliance, says yes. Wilke’s organization sued Bremerton in the early 1990s for egregious releases of sewage waste. Now he points to the reopening of shellfish beds near Bremerton to commercial and recreational harvest by the Suquamish Tribe as evidence that CSO improvements are a smart investment. He cites a study by the National Resources Defense Council that ranked Washington 14th in beach water quality as proof that more work is needed. The number one cause of beach closures: sewage spills and overflows.

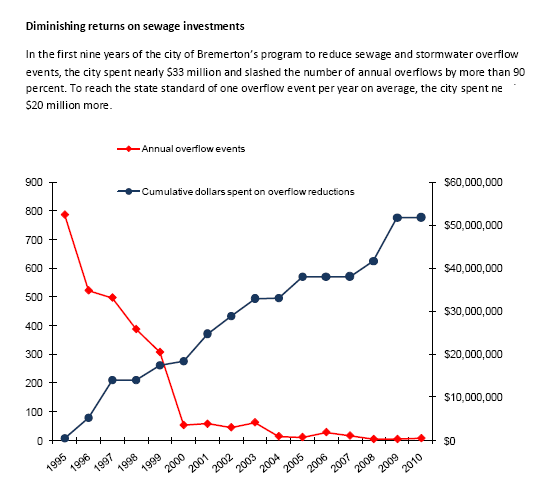

Getting raw sewage out of the water and making clams safe to eat are terrific environmental accomplishments, no doubt about it. But as Bremerton found, the local shellfish beds were deemed safe years before the city reached the one spill goal. As the chart below shows, in 2003 — the year the beds reopened — the city had spent just over $30 million and made huge reductions in the number of CSO events. But to reach the state benchmark, Bremerton’s ratepayers spent nearly $20 million more.

The disconnect between cost and benefit experienced by Bremerton in the later years of its CSO project likely will help inspire the chorus of voices questioning the region’s focus on CSOs. The Times’ story quoted a slew of water-quality heavy hitters: Pam Bissonnette, former director of Natural Resources and Parks for King County; Kevin Clark, former manager of what today is Seattle Public Utilities; Bill Ruckelshaus, former EPA administrator and former chairman of the leadership council of the Puget Sound Partnership; David Dicks, member of the leadership council and former executive director of the Partnership; and Don Theiler, head of King County’s waste water division. All cast doubt on the wisdom of investing so heavily in CSO work at the expense of other pollution projects.

Smarter standards and spending

So what’s the answer? Two things need to happen. First, Puget Sound leaders need to sit down and have a frank discussion to evaluate the real threat posed by CSOs. As Mapes states in her story, the Puget Sound Partnership suggested nearly two years ago that regulators and others meet and come up with a more cost-effective way to improve water quality in urban areas like Seattle and King County than through sewage projects, but the meeting hasn’t happened. And “talk of re-examining priorities got started in 2008 under former King County Executive Ron Sims. Then he and others involved in the discussion went on to other jobs,” Mapes reported.

The second fix is for the rule of one overflow per outfall. This is an oddly arbitrary requirement. It’s not linked to how much damage the spill is causing or how concentrated or vast the volume of pollution is. And why one spill? Why not zero, or 10? Ecology manages a zillion National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) water quality permits that are based on the amount of pollution being dumped. Why can’t CSO permits work similarly?

Admittedly these changes would require opening big old Sani-Can of worms. It’s an open question whether Ecology even has the legal authority to make this change, and we’re certainly not advocating a weakening of rules that would further harm the Sound. There’s also the fact that just because dollars could be saved from CSO projects that provide diminishing returns, it’s uncertain that these desperately needed resources would be redirected to cleaning up polluted stormwater runoff or other menaces to our swimming and clamming waters.

But in an ideal world — one where we made the most cost-effective environmental investments first — we’d change the existing rule to allow our limited funds to be spent where the experts say they’re most needed, which for Puget Sound would likely mean an investment in controlling stormwater runoff. And because too much stormwater is the underlying problem with CSOs, projects to reduce toxic runoff, particularly green stormwater solutions, would often help control sewage spills as well.

Sightline’s Making Sustainability Legal project identifies specific regulatory barriers to affordable, green solutions. If you’ve come across such an obstacle, please let us know by writing Eric (at) Sightline (dot) org.

Comments are closed.