Editor’s note: This book review was written by guest blogger Patrick Barber. Patrick lives in Portland, Oregon, where he works as a graphic designer, writer, and vegetable seller. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of Sightline.

Bike books are like bike infrastructure. Their purpose is either to attract new riders, or appeal to experienced users. Effectively appealing to both groups is difficult, if not impossible.

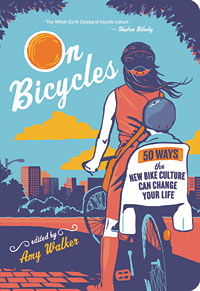

Yet that’s what On Bicycles: 50 Ways the New Bike Culture Can Change Your Life does. It’s an all-around guide to bike culture, filled with useful information and bursting at the seams with earnest enthusiasm for all levels of interest. But will this self-proclaimed bike culture make the bicycle a vital part of North American transportation networks? Does bike culture necessarily help to bring bicycling to the mainstream as a method of transportation?

Amy Walker, the editor of On Bicycles and a co-founder of Vancouver’s Momentum magazine, is a foremost authority on North American bike culture. Her work at Momentum provides her with a unique perch where she has watched bike culture grow. Her book is an extension of that work—a collection of stories that draws on her reach as an editor, writer, and expert in bike culture.

On Bicycles is a charming, well-designed book that easily slips into your messenger bag. The essays are peppered with photographs and a splendid collection of illustrations. In its expansive scope, the book progresses from essays aimed at prospective riders, to stories for experienced cyclists, to essays and how-to pieces for the die-hard bike nerd who is obsessed with both pedaling and policy.

There are some thoroughly enjoyable and well-written essays here, from knowledgeable writers and culture mavens (many Cascadian!) such as Grist columnist Elly Blue, Portland Mercury reporter Sarah Mirk, and Oregonian reporter and author Jeff Mapes.

Walker’s pieces are some of the book’s best. Without straining to convince the reader, she draws on her experience as a journalist, often interviewing several subjects and weaving their words together with her prose to produce an invitingly conversational story.

Yet other essays are less compelling: one declarative statement after another, creating a list of evidence rather than an inviting narrative. Writing that comes off dry and pushy holds little appeal for readers who are new to the subject.

In her piece “Less is More,” Walker encapsulates the best and worst of what On Bicycles has to offer. Using a lens of transcendentalism to examine how bicycling can help you lead a simpler life, she writes,

Offered unlimited power, humans are easily seduced. We overshop, overeat, and overdrive, and then wonder how we got to be overdrawn, overweight, and overtired. We need limits: the external limits set by our bodies and our intuition, and external limits that we create as a society. Riding a bike to get from A to B—and restricting our ability to compulsively drag stuff back to our dens—is a positive kind of limit.

Cyclists know intimately how much time and energy a trip across town will take. And we’re not all athletes! We schedule trips to include multiple stops or errands rather than expending more energy by taking several separate trips. Modest consumption habits and voluntary simplicity are an inherent part of the cycling lifestyle.

In this excerpt, Walker captures much of what is good and bad about the notion of bike culture as a separate microcosm within North American culture. As a bike rider myself, I know what she means. Bicycling slows you down, allows you to greet your neighbors and take in the world in a way that driving a car—or even riding the bus—does not. I appreciate the convenience that a car offers, but I don’t like using one day after day—I miss the physical and social sensations of being on a bike in my city. But the idea that one must engage in “voluntary simplicity” to use a bike is exactly the kind of thinking that keeps bicycling from becoming a mainstream, everyday activity in our culture. People in places with established cycling cultures—yes, Amsterdam and Copenhagen—don’t see themselves as living lightly on the earth. They’re just living. How can bicycles evolve from a specialized, exclusive culture to an inclusive, everyday culture? As fun and engaging as On Bicycles is, it fails to address this crucial question.

I came away from On Bicycles wondering if it would be more effective if it were broken into a few different books: a quick and easy-reading guide (ideally fully edited/written by Walker, and not just a curated collection of essays) for novice bicycle users; a gear-oriented how-to book for regular riders; and a weighty tome on policy, culture, and advocacy writing to appeal to the wonks out there. As it is, On Bicycles attempts to be all things to all people, and it’s less effective as a result.

There’s a deeper question here. If our goal as policymakers, advocates, and planners is to improve the transportation system by putting more people on bikes, what do we need from books like this, beyond that first, convince-the-curious section? Once people are using bikes, do we really need “bike culture”? How long will it be before an American can simply ride a bike, without having to become a “cyclist”?

The book’s subtitle—50 Ways the New Bike Culture Can Change Your Life—suggests a question: What if riding a bike didn’t change your life? What if it just got you where you wanted to go, in a boring, everyday kind of way? Would we lose anything essential, or would we be closer to a sensible approach to urban transportation? I tend to think the latter: as much as the nerd in me enjoys bike culture, I’ll be even happier when I can be a person, and not a cyclist, simply because I use a bike to get somewhere on a rainy day.

Comments are closed.