What if all it took to build better neighborhoods was a little paint?

Walking in Southeast Portland, I once stumbled on a horizontal rendition of a sunflower, painted curb to curb on the intersection of Southeast 33rd and Yamhill (pictured above). Sunnyside Piazza, it is called, which may seem a bit much for a splash of color on asphalt, but in person, it seemed fitting. This whimsical design, interrupting the functional but monotonous gray of Portland’s street grid, felt like a somewhere. It seemed like a place deserving a name. It even felt like a “piazza.”

That was in 2002. I later learned that the Sunnyside Piazza was the second painted public square in Portland, facilitated by the non-profit City Repair Project. Now, dozens of painted plazas, dubbed Intersection Repairs, pepper the map not just of Portland but also of Los Angeles, New York, St. Paul, and Seattle.

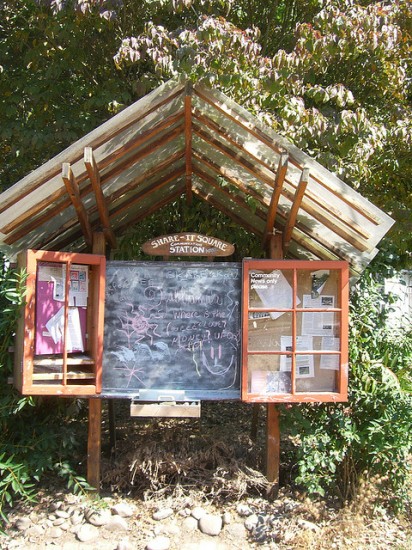

It all started in the mid-1990s with Share-It-Square, in Portland’s Sellwood neighborhood, where architect and City Repair co-founder Mark Lakeman lives. After visiting villages in Central America where residents gather around common spaces, Lakeman decided to bring similar spaces to Portland. “Putting the public space back where it’s supposed to be may not sound like a huge change,” Lakeman says, “but it has a profound effect on the social culture. . . . We know that Americans are more lonely and isolated than ever before, but we don’t realize that the absence of cohesion in American communities is totally related to the absence of places where people can actually build that.”

Looking at his own neighborhood, Lakeman decided to transform the intersection of Sherret and 9th from a car-dominant space to a public place (documented in this video). He thought this change fitting, as cultures throughout history have come together at crossroads. Of course, there was still the question of how to take an intersection—an endlessly repeated but utterly non-convivial fixture of the city’s street grid—and turn it into a place. Lakeman and his neighbors’ brilliance was in the simplicity of their brainstorm: paint a picture.

Lakeman and his neighbors gathered community support and approached the City of Portland. The Portland Department of Transportation (PDOT) was taken aback by the idea of painting a design in the middle of the intersection. One city official told Lakeman, “That’s public space. Nobody can use it.” The residents went guerrilla: they painted without permission.

PDOT was furious. Officials threatened to sandblast the design off the roadway. But the neighborhood gained political support from Councilmember Charlie Hales and Mayor Vera Katz. When the city surveyed the neighbors living near Share-It-Square, they found residents had positive perceptions of less crime, slower traffic, and increased neighborhood involvement. Seeing that the painted intersection hadn’t cost the government a dime, the politicians quickly moved to pass a city ordinance that allowed painted intersections throughout Portland.

More neighborhoods began painting intersections and Intersection Repairs spread. After working together, newly empowered residents were able to enjoy their local gathering spots. Once they saw the value of public spaces, residents wanted to make more improvements. Adjacent to Share-It-Square, residents have added amenities that double as public art. For instance…

there is a 24-hour tea station that neighbors keep stocked with tea and hot water…

a local newspaper stand, fashioned as a beehive because it houses the community newspaper, the Sellwood Bee…

an exchange station where neighbors can leave items they don’t want any more or give away extra produce from their gardens…

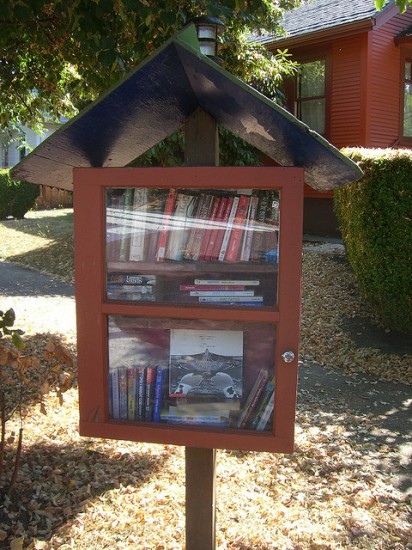

a community library to leave or take books…

and a children’s play structure where kids can gather while parents lounge on nearby benches or peruse the information kiosk (below).

“It’s not about the paint,” says Professor Jan Semenza who lives near the Sunnyside Piazza and has researched intersection repairs. “It’s about neighbors creating something bigger than themselves.” As an everyday intersection becomes someplace special, residents begin to experience the value of community. Neighbors paint themselves out of a corner – of the intersection, of their individual homes – and into the middle of the street. By turning an intersection from a dividing line between neighbors into a gathering place, residents begin to solve the problems that plague neighborhoods and cities. Where isolation existed, they find community. Where cars dominated, they create a people place. With a little paint, neighbors are solving big problems.

Once purely a Portland phenomenon, intersection repairs are popping up in other cities. In Seattle, a City Repair chapter formed and facilitated several intersection painting projects including a ladybug in Wallingford and a turtle in Fremont. The ladybug turned six this year, and residents meet annually to repaint the mural and hold a block party. Eric Higbee led the ladybug painting. “Our goal is to cut down traffic and bring the community together and create a sense of neighborhood,” Higbee told the Seattle Times.

Portland State University professor and City Repair organizer Pedro Ferbel-Azcarate confirms the traffic-calming value of street painting: “When you have a neighborhood place where there are people on the streets, the cars will slow down.”

While her parents initially thought of painting the street at 41st and Interlake Avenue North in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, eight-year-old Ella Sauer came up with the turtle theme. The family then approached neighbor Bill Lindberg with the plan, and Lindberg helped bring residents together and work through the permitting process. The turtle cost a little more than a thousand dollars, including Seattle Department of Transportation permits; the residents received a Neighborhood Matching Fund grant for half of the cost. Painting their street brought neighbors together in a way not typically possible during the daily routine: “This is the only way I’m able to meet my neighbors on a personal level,” said Kate Gengo, a four-year resident of the neighborhood.

At its core, intersection painting is about community empowerment. In Portland, City Repair doesn’t seek out neighborhoods to encourage residents to paint the street. They wait for neighbors to come to them. City Repair will then work as facilitators, helping residents choose a design and encouraging them as they knock on doors to garner support for the painting. While the painted mural is a beautiful end product, it’s the relationships and sense of community formed through the process that makes these places become villages within the city.

The process of creating a public square empowers the residents and builds relationships, but it also leaves evidence on the ground that something is different in the neighborhood. “It sounds whimsical, but then you go walk around [the Intersection Repair] on a Saturday afternoon and you get it,” says supporter and former Portland city councilor Charlie Hales. Neighbors are talking, cars drive slower, and you can tell you are in a place. When people drive or walk through an Intersection Repair project, they are inspired to reshape their own neighborhoods. City Repair now has facilitated hundreds of community-building projects throughout Portland.

Jan Semeza, a professor of public health at Portland State University and a neighbor of the Sunnyside Piazza, decided to turn his neighborhood into a laboratory. He had students canvass the Sunnyside neighborhood and also survey a similar neighborhood without an Intersection Repair. While there are not enough data to pinpoint the exact reasons, it appears that the Sunnyside Piazza neighbors considered themselves healthier (86 percent in excellent/very good general health compared to 70 percent), happier (57 percent felt “hardly ever depressed” versus 40 percent), and content with their neighborhood (65 percent said their neighborhood was “an excellent place to live” versus 35 percent). Also, police calls from the Sunnyside Piazza neighborhood decreased after the painting project.

Near Share-It-Square, Mark Lakeman sees residents staying rooted in the community. “Americans move every four to seven years,” Lakeman says, “and that period of time is visibly lengthening right around that intersection because people want to live there. Families are clustering around it, having kids or bringing their kids, so there are more children—and more shared childcare, and more adults interacting with kids on that street.”

Share-It-Square, aerial view, from Google Maps. View Larger Map

Flying over cities, whether in an airplane or virtually (above), streets and homes extend for miles, with little to distinguish them. But then you see some color: a painted intersection in a sea of roofs and concrete. These are villages within the city—where locals have come together and said this is a place. A painted intersection might seem trivial. It doesn’t cost much or last very long. But the important work is done behind the scenes. Residents join together. They fashion gathering spaces. And it all starts with some paint.

Guest blogger Alyse Nelson is a city planner for a small town in Kitsap County, Washington. She spends some of her spare time researching for Sightline on topics such as pedestrian carts, cargo bikes, and family-friendly courtyard housing. She last wrote for Sightline about reclaiming urban alleys as vibrant public spaces. Alan Durning edited this post.

Comments are closed.