Editor’s Note: This guest post was written by Kamala Rao, MCIP, an urban planner and Sightline board member. Her husband, Bryn Davidson, is co-owner of Lanefab Design/Build, a company that specializes in laneway housing.

There’s an alley renaissance going on around the world.

There’s an alley renaissance going on around the world. It was born of a renewed love for urbanity that came along with the droves of young, artistic types shunning the ‘burbs and re-populating North America’s inner cities. They brought with them a desire to turn what have traditionally been neglected and ugly inner-city dumping grounds into vibrant, art-adorned, pedestrian-friendly public spaces.

Vancouver, BC—the city that has served as a North American icon for creating liveable inner cities—is having its own “laneway” renaissance (as alleys are known here). However, in Vancouver, the revival was spawned by sky-high real estate prices, a lack of affordable housing, and an ingenious plan to create ‘hidden density’ in the city’s most desirable single-family neighborhoods. Whereas some might see these underutilized swaths of pavement as merely needing a little beautification, the City saw it as an opportunity to provide badly-needed rental units.

Before I get in to all the reasons why I love this new housing concept, first a bit of an explanation. Laneway homes are basically miniature versions of single-family homes—in the range of 500 to 1,000 square feet—that are built in what has traditionally been the garage location of a single-family lot: in the backyard facing the lane. They can’t be sub-divided or sold separately from the main house on the lot. They can only be used for additional family space or rental income. Their introduction into the frenetic Vancouver real estate scene was part of a larger “Eco-Density Initiative” invented by former mayor Sam Sullivan and championed by current mayor, Gregor Robertson. The intention is to “help reduce [the city’s] carbon footprint, expand housing choices, and ensure Vancouver remains one of the most liveable cities in the world.”

Here are four reasons I love them—and hope to see other cities throughout the world adopt them as a housing option:

1. They add ‘hidden density’ to single-family neighborhoods

The concept of “laneway housing,” is actually quite ingenious. Think about it: what other city has successfully added density to long-established, single-family neighbourhoods filled with $1 million-plus homes? The very thought of it conjures up images of staunch NIMBYism. The City of Vancouver’s deft branding and effective outreach smoothed the roll-out of its laneway housing bylaw, keeping NIMBY opposition to a minimum.

First of all, the city chose a good name. The term “Eco-Density” reminds people of the significant environmental benefits of compact communities, while neutralizing many of the concerns about noise, traffic, and the erosion of the idealized, bucolic single-family neighborhood.

Secondly, the City knew that adding density the traditional way – by “up-zoning” to allow for multi-family dwellings – was going to be a non-starter in these tony neighborhoods. In light of the great condo boom of the last two decades, the City saw the value in preserving the remaining single-family housing stock. Because no matter how much you recognize the environmental benefits of density, no one would ever want to see these beautiful, traditional neighborhoods—with their lovingly refurbished, turn-of-the-century homes and tree-lined streets—destroyed to make room for more glass-and-concrete towers.

The goal was to densify single-family neighborhoods without affecting their character; so the density needed to be relatively invisible with no impact on the curb appeal of these long-established and highly-sought after neighborhoods. They had already legalized basement rental suites—the most invisible form of increased density—but were bold and committed enough to ask themselves if they had actually done all they could do to increase housing options in the least dense parts of the city.

Thus, laneway housing was born. The bylaw that gave birth to the concept was passed in July 2009 and less than a year later, one hundred of these pint-sized backyard homes had been permitted. Today, they are becoming a relatively common sight in the back alleys of many Vancouver neighborhoods.

2. They’re ultra-green

Since World War II, our homes have gotten successively bigger, consuming a large amount of resources to build, furnish, heat and cool. Of course, the smaller your home, the less energy and resources it consumes. Laneway homes, by virtue of their size, are already nearly as energy-efficient as condos, and at least one builder of laneway homes is taking it a step further to see just how green these homes can be.

The firm builds exclusively with pre-fabricated, ultra-insulated panels (R-40, for you green building geeks out there). They also use small, energy-efficient appliances; triple-glazed windows; and optional solar panels, wind turbines and rainwater collection, in order to make these green little houses even greener. The company is just now building its first “net-zero” laneway home (meaning that it will collect all of the energy it consumes via solar panels), which is loaded with the latest in energy-efficient design features.

3. They provide a totally new housing option for those who can’t afford Vancouver’s sky-high home prices

Most of the public conversation about laneway housing has centered on sustainability and boosting the rental housing stock. But I wondered what it was like to actually live in one of these backyard micro-homes. After all, they really are a rare type of housing: a free-standing structure the size and cost of a condo. So, I contacted Mathew Arthur, who lives in the first laneway house built in Vancouver. At the time I spoke with him, he’d been living there for over a year.

Mathew—a designer himself—appreciated the modern design of the tiny home from the moment he saw it and knew he had to live there. “In Vancouver, if you’re a renter, you basically have two options: to live in an old house that’s been cut up into apartments and probably not very well kept up over the years, or to live in a condo, but this is completely different. It’s the same price and modern design as a new condo, but I have a whole house. There’s no one above or below me and I have direct access to the outside.” As Mathew pointed out, laneway houses allow people who can’t afford to buy (and there are many in Vancouver with its average detached home price now above $800,000) to have their own little piece of land.

When I asked Mathew if it was challenging living in such a small house—which he shares with his brother and most nights, one or both of their partners—he told me that it’s a difficult question to answer. He doesn’t feel like the space, which is just over 700 square feet, is small. “The house is so well-designed, it makes it easy to live in a small space. Hopefully the creation of smaller housing like this will help us as a society to re-focus on good design versus just creating unnecessarily large, cookie cutter spaces.”

Good point: as our urban populations grow and densify, urban land becomes more scarce—and the price of all the resources it takes to build and power a home continue to climb—laneway housing can indeed be a model for living well within a constrained future.

4. They’re just down-right adorable

To make this point, I’ll finish here and let the photos do the explaining. Enjoy!

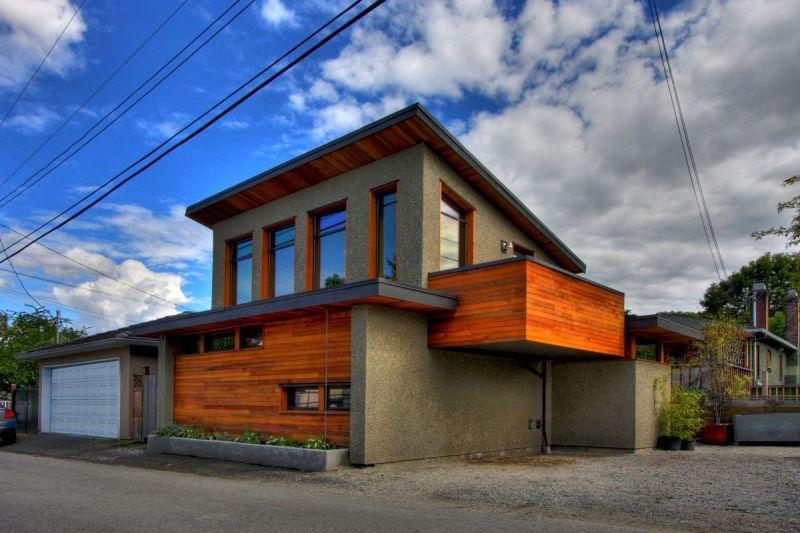

A view of a laneway home in Vancouver’s west side, from the owner’s backyard. This home is being rented out by the owners as a vacation rental at $300/night:

Interior view of the same west side laneway home:

Interior view of the same west side laneway home. A pint-sized bedroom in a pint-sized home:

“Lanescaping”: The City requires that landscaping be added on the lane side of the home:

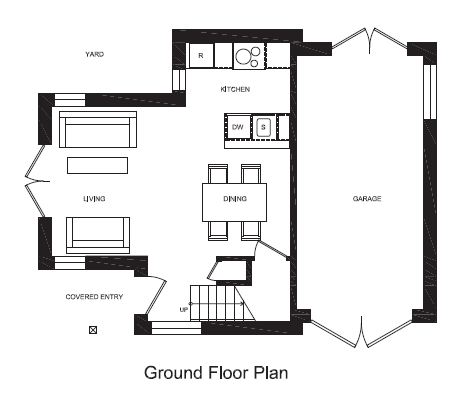

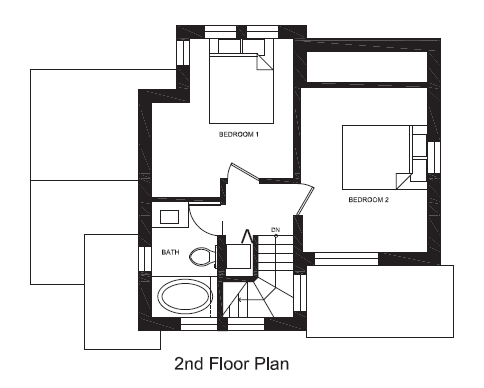

Floor plans: open concept living dining and kitchen:

The owners of this lane house are moving in and renting out their main house:

Have your own photos of laneway houses? Submit them to Sightline’s Flickr photo-pool.

Comments are closed.