Here in the US, we’re so used to measuring a car’s efficiency in “miles per gallon” that it seems impossible to think that there might be a better way.

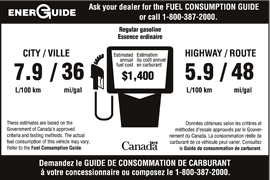

But there is, and it’s used just north of the border. In addition to miles per gallon, Canada’s fuel efficiency labels use a far more revealing and intuitive measure: “litres per 100 kilometres.” The important thing isn’t the switch to the metric system, it’s that the division is flipped on its head. The distinction between “miles per gallon” and “gallons per mile” might seem trivial, but it makes all the difference between confusion and enlightenment.

But there is, and it’s used just north of the border. In addition to miles per gallon, Canada’s fuel efficiency labels use a far more revealing and intuitive measure: “litres per 100 kilometres.” The important thing isn’t the switch to the metric system, it’s that the division is flipped on its head. The distinction between “miles per gallon” and “gallons per mile” might seem trivial, but it makes all the difference between confusion and enlightenment.

Here’s an illustration. Imagine that your car gets just 10 mpg, and you upgrade to a car that gets 20 mpg. And at the same time, imagine that your neighbor boosts her car from 40 mpg to 50 mpg. In both cases, it’s a 10 mpg improvement—which would make you think that the two shifts have done the same amount of good.

Not so!

Turn the math on its head, and you’ll see why. The 10 mpg car burned 10 gallons every 100 miles. The new 20 mpg car burns 5 gallons every 100 miles. So the upgrade from 10 mpg to 20 mpg saved 5 gallons of gas for every 100 miles of driving. But your neighbor shaved her gas consumption from 2.5 gallons per 100 miles to 2 gallons per 100 miles—saving just half a gallon of gas every 100 miles.

In short, the upgrade from 10 mpg to 20 mpg was 10 times as important as the upgrade from 40 mpg to 50 mpg. And yet, both upgrades involved an increase of 10 mpg.

For more examples of mpg math, I’d encourage you to play with this great new fuel efficiency calculator from David Kroodsma at climatecentral.org.

As we’ve written before, the miles-per-gallon view of fuel efficiency can focus our attention on the wrong things. People who care about reducing oil consumption naturally focus on the cars with really high mpg ratings. A car that gets 100 mpg seems so much better than a car that gets just 50 mpg! But for oil consumption, the biggest bang-for-the-buck is at the low end. Shifting one vehicle from 15 mpg to 20 mpg can save nearly as much fuel as getting a Prius driver behind the wheel of an all-electric Leaf!! But in order to see the importance of boosting fuel efficiency at the low end, Americans have to do some arithmetic—while Canadians can see the difference at a glance.

Luckily, EPA itself is taking steps to deal with the flaws in mpg math. They’ve just announced a new fuel economy label that focuses on how much money people spend on gas—which is the same thing, basically, as how much gas they consume for a given amount of driving. And in an especially clever move, the label tells you how much money you can save (or lose!) over five years by choosing a particular car, compared with the average car or truck sold. In short, the new label turns fuel efficiency into a pocketbook issue—and one that’s immediately apparent, just when car shoppers are already focused on a car’s sticker price. Smart move!

Evan Manvel

I’ve long wanted to require cars to have dashboard readouts of current fuel efficiency based on driving (like many cars do now), ideally with an average cost per mile (or total trip cost) readout. Seems like that improves some people’s driving habits (i.e. cuts on the hard brake and acceleration issues) as well as reminding them of the marginal costs of driving.A mental challenge with the gallons per hundred miles is that people have to get used to the smaller numbers being better. There are a few places in life that’s true (cholesterol, golf), but usually higher numbers are better.Yet the dollar costs (and scale pollution ratings) are probably the best thing here, and could eventually replace the MPG or GPhM ratings as the most prominent numbers. Grades for the pollution ratings would have been better than the scales, but you can’t win them all.

spudboater

The irony of all of this is that it still makes more sense to drive your existing vehicle into the ground. I drove my 1990 Subaru Legacy Wagon to 185,000 miles over a 9 year period and retired it when the cost of repairs exceeded the value of the vehicle and its condition. But to have replaced it for a vehicle that got 5 miles more per gallon did not make economic sense. If you lease a vehicle or trade in for a new one every three years (do people still do this?) then getting a vehicle with better mileage makes sense. The bottom line is there is more to a vehicle cost than simply the gas, when one takes into account production costs, use of steel, plastic and host of other materials. But certainly EPA’s move toward looking at real costs to drive 100 miles would be a better indicator, than MPG. And anyone who hauls toys around like kayaks, skis, trailers etc will tell you that MPG only gives you an ideal, not anything close to reality. My current 6 cyinder vehicle is supposed to get 22 to 27 mpg. The only time it ever got 27 mpg was on the highway with nothing on the roof, with a tail wind. With snow tires in winter it’s closer to 18. For city driving it’s closer to 21. For road trips with my kayak or skis on top it’s 22 to 24.

Chris Troth

As important as the message is about how dramatic a percentage gain you can get by improving fleet efficiency at the low end of the MPG scale (especially as so much of the new vehicle fleet remains light trucks/SUVs), I think the core message has to be, “If you need a motor vehicle, always choose the most efficient one available that meeds your most common needs.” Of course, that needs to be prefaced by the message that you can save yourself some serious dough by not owning a motor vehicle at all and walking/biking/bussing/renting/borrowing instead, as needed.Returning to the topic, less fuel burned = less carbon dioxide and other pollutants going into the atmosphere, and that is what we need to achieve, whether from more efficient and less polluting vehicles, or from using less efficient vehicles less frequently.Realistically, motor vehicles aren’t going away before we do due to their utility, the nature of our built environment and societal expectations. Also, autos are still a major purchase, requiring financing for most buyers, and therefore something they buy only rarely, even if they don’t plan on driving their vehicle into the ground (a good idea, I agree, in many, but certainly not all cases).My point is that most drivers are not going to have fuel efficiency as the primary, or even secondary determinant of their vehicle choice, which is too bad, unless their current vehicle becomes suddenly uneconomic for them. But when a new vehicle is purchased it is always better to purchase a more efficient one (preferably the most efficient available), because, while drivers who upgrade from from 10 MPG to 20 MPG cut their fuel use in half, they are still using more than twice as much fuel per mile driven as the drivers who go from 40 MPG to 50 MPG. And the drivers of the new 50 MPG vehicles are burning less fuel than they used to, which is the goal, and is never to be disdained, even if it isn’t a 50% improvement.The new EPA labels are a great improvement, and will no doubt help at the margin, but will probably not be as important as the rising cost of fuel in getting drivers into more efficient vehicles. But anything and everything that the government can do to improve the efficiency of the fleet going forward should be done, because that is where the real meat is. We need higher fuel taxes, higher CAFE requirements, a requirement for engine shut-off when stopped (ie, make every new vehicle a mild hybrid), and a permanent cash-for-clunkers program to take the least efficient vehicles out of the used car market and recycle vehicles that would otherwise sit around leaking toxics. Continuous improvement of fuel efficiency of all parts of the vehicle fleet is critical.And here is the argument for not driving your relatively efficient vehicle into the ground, *if* you can afford a new, more efficient vehicle (and still need one). You will simultaneously maintain demand for efficient vehicles, and put your relatively efficient old vehicle into the used-car market, allowing someone who can’t afford a new car to upgrade the efficiency of their ride (probably – maybe the purchaser’s old car was just as or more efficient, but most likely not).I tend to largely discount the carbon cost of manufacturing, not because it is insignificant (it is very significant), but, because like it or not, by the time I purchase something, the carbon burnt to make it and (most of the carbon) to transport it to me is already in the atmosphere, regardless on whether I buy the product or not.