Researchers have pointed the finger at stormwater runoff as the top source of pollution that’s getting into Puget Sound and other Northwest waterways. And because runoff comes from just about everywhere—roofs, roadways, parking lots, farms, and lawns—the solution has to be just as widespread.

Researchers have pointed the finger at stormwater runoff as the top source of pollution that’s getting into Puget Sound and other Northwest waterways. And because runoff comes from just about everywhere—roofs, roadways, parking lots, farms, and lawns—the solution has to be just as widespread.

Enter 12,000 Rain Gardens.

This week Washington State University and Stewardship Partners, a nonprofit working on land preservation, announced a campaign to promote the installing of 12,000 rain gardens around Puget Sound by 2016. The website even has a counter tracking the number of gardens and encourages folks to enter their rain garden into the database.

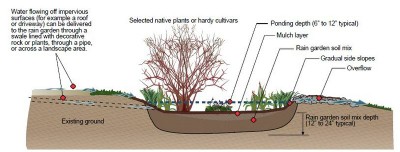

Here’s how a rain garden works. The garden is essentially a sloped ditch or pond that’s typically about 6 to 12 inches deep. The bottom of the depression is 1 to 2 feet of a soil mix that’s more absorbent than regular dirt. The garden is planted with shrubs and grass that can tolerate soggy soil.

Rain runoff is channeled into the garden, perhaps with a pipe that connects to a roof downspout or through a gap in a street curb that funnels road water into the depression. There’s also a route out of the garden should it overflow, which can be a drain linking to the stormwater system or into another area of the yard or road.

It’s a nice idea, but is 12,000 Rain Gardens just a feel-good gimmick that won’t amount to much?

I don’t think so, and in two words here’s why: Curtis Hinman.

Hinman is, in hyperbolic terms that I love for blog posts, the Northwest’s stormwater messiah.

He literally wrote the book on building Northwest rain gardens (I had trouble calling this up in Firefox, but not IE).

He’s the director of WSU’s Low Impact Development Research Program in Puyallup, home to a facility for testing green stormwater solutions that’s one-of-a-kind in the nation.

He helps teach engineers, land-use planners and other public and private employees how to incorporate natural stormwater strategies into projects. With his science-based results and training sessions that show that rain gardens and pervious asphalt and concrete really do work—that they can soak up serious volumes of runoff—he’s spawning stormwater converts around the Northwest.

And Hinman is a supporter of the 12,000 Rain Gardens initiative. The new campaign makes heavy use of WSU’s expertise on rain gardens, including Hinman’s Rain Garden Handbook for Homeowners and a video from the university showing how to build a rain garden.

The 12,000 Rain Gardens site helps walk people through important considerations for installing a rain garden, including:

- How to determine how much impervious surface you have, and how much of that water you want to manage

- How to decide where on the property you’d like to build a Rain Garden

- How to do a percolation test, to make sure the soils can soak up the water

- How to decide how big to make the Rain Garden in the space that you have

- Construction steps

- Planting ideas

- How to maintain your Rain Garden

There are also free two-hour training sessions offered through the initiative that are coming up later this month and next in Tumwater, Puyallup, and Olympia. And if you’re looking for rain garden inspiration, the site also has a huge list of projects with addresses and contractor’s names, arranged by county.

So don’t let Seattle’s recent rain garden snafu scare you off—rain gardens can and do work in the Northwest. If you’re outside the Puget Sound area, there is plenty of support for rain gardens elsewhere. In Portland, there’s a workshop in May through CNRG (which stands for what, I don’t know), and the Oregon Environmental Council has great resources for stormwater fixes.

Rain garden photo from Seattle’s High Point development taken by Lisa Stiffler. Rain garden diagram from Curtis Hinman’s Rain Garden Handbook for Homeowners.

Comments are closed.