There’s plenty of evidence that building roads doesn’t do much to relieve congestion. This fairly exhaustive literature review from the Victoria Transport Policy Institute shows that building new road space in an urban area tends to encourage drivers to take advantage of faster-moving traffic by making extra trips.

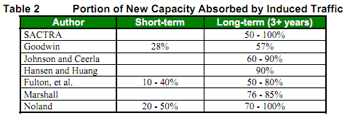

Estimates vary, but it seems that somewhere between most and all of any new road capacity is quickly occupied by new “induced” traffic. (See, for example, the chart to the right from the VTPI lit review.)

Estimates vary, but it seems that somewhere between most and all of any new road capacity is quickly occupied by new “induced” traffic. (See, for example, the chart to the right from the VTPI lit review.)

Reading this body of literature, Brookings Institution researcher Anthony Downs argues that traffic congestion has become an inescapable fact of urban life. In fact, he argues, the steps we take to fight congestion—such as building new roads—often carry the seeds of their own destruction:

Visualize a major commuting freeway so heavily congested each morning that traffic crawls for at least thirty minutes. If that freeway were magically doubled in capacity overnight, the next day traffic would flow rapidly because the same number of drivers would have twice as much road space.

But very soon word would get around that this road was uncongested. Drivers who had formerly traveled before or after the peak hour to avoid congestion would shift back into that peak period. Drivers who had been using alternative routes would shift onto this now convenient freeway. Some commuters who had been using transit would start driving on this road during peak periods.

Downs calls the shift of drivers from other times, routes, or modes the principle of “Triple Convergence”—a force that tends to keep traffic congestion at a rough equilibrium regardless of how much money a metro area throws at road construction.

But to me, that raises an interesting question: if a city can’t build it’s way out of traffic congestion by adding new roads, what about investments in transit? Transit advocates sometimes argue that bus or rail investments can help ease traffic, by getting people out of their cars.

Yet as far as I can tell, the evidence for this isn’t so good.

- This paper by researcher Antonio Bento and colleagues suggests that significant increases in bus service have essentially no effect on vehicle travel. Rail service increases do decrease vehicle travel, but by a surprisingly modest amount.

- This paper by researchers from the University of Toronto found—unsurprisingly—that increases in road capacity were quickly matched by increases in traffic volumes. But it also found that increases in transit service had no effect on traffic volumes. In the authors’ words: “these results fail to support the hypothesis that increase provision of public transit affects [vehicle miles traveled].”

- And this study from a University of California-Davis found that higher residential densities and greater land use mix did decrease vehicle travel—but found no statistically significant link between better transit service and less driving.

I’m sure that there’s more literature on this issue, some of which finds stronger connections between transit and vehicle travel. But in general, based on what I’ve found I have to align myself with Anthony Brooks and transit planner Jarrett Walker, who both argue that transit investments have little impact on how much driving goes on in a crowded urban area. To quote Walker:

To my knowledge…no transit project or service has ever been the clear direct cause of a substantial drop in traffic congestion. So claiming that a project you favor will reduce congestion is unwise; the data just don’t support that claim.

Transit is good for an awful lot of things. It helps move people to where they want to go; it gives people who prefer not to drive, or who can’t drive, a decent transportation option for many trips. It can reduce a region’s reliance on risky fossil fuels; and on and on. But for folks who hope that transit investments will offset the impacts of road expansions—well, sadly, I don’t think the evidence lines up that way.

Comments are closed.