[WARNING: As mentioned in the comments below, this post’s discussion of the “Coase theorem” contains several errors—most notably, that Coase himself did not present his arguments mathematically. In fact, according to a number of sources, there really is no single “Coase theorem”—instead, there are several different and somewhat conflicting notions that followers and interpreters of Coase have presented as theorems. For more, please read the comments, below.]

Those inclined to be uncharitable might see the phrase “free-market environmentalism” as somewhere between oxymoronic and greenwashing. But I’m a charitable sort: I believe that people can be sincerely committed to caring for the planet—and also firmly committed to the idea that free-market principles offer the best hope of doing so.

Those inclined to be uncharitable might see the phrase “free-market environmentalism” as somewhere between oxymoronic and greenwashing. But I’m a charitable sort: I believe that people can be sincerely committed to caring for the planet—and also firmly committed to the idea that free-market principles offer the best hope of doing so.

And sometimes, markets really can be great tools for advancing sustainability. Consider the problem of overfishing: some great successes in fisheries management have come from giving individual fishers a “property right” to a share of each year’s harvest. Once those rights are established and firmly enforced, fishers have incentives to boost future years’ harvests—because an abundant fishery increases the value of their “property”—and also to keep an eye on their neighbors to ensure that they’re not taking too much of a shared resource. As it turns out, giving individuals the incentive to act both as stewards and enforcers can be a pretty effective combination. (This National Research Council report has more details—but I should be careful to note that the study found that transferable fish quotas are no panacea.)

As for fisheries, so for air and water? Free-market environmentalists would say yes: the best way to guarantee clean air and fresh water, they’d argue, is to establish clear property rights for pollution, and let the market sort things out. Many even argue that a property-rights based system could lead to major reductions in pollution, since governments sometimes allow more pollution than people actually want.

But unfortunately, free-market sincerity only goes so far: it’s possible to be perfectly sincere and also deeply misguided. And, in fact, that’s the conclusion that this article in the Journal of Economic Issues reaches. The authors, Robin Hahnel and Portland-based Kristen Sheeran, have constructed a convincing case that the key intellectual pillar of free-market environmentalism—a bit of theoretical economics known as the Coase theorem—has almost no relevance to how pollution markets would play out in the real world.

So what’s this Coase theorem thing all about?

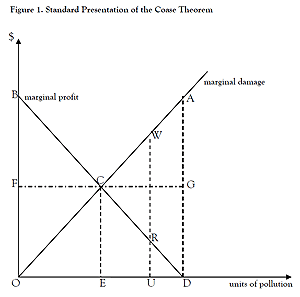

In a nutshell, Nobel-winning economist Ronald Coase proved mathematically that, with a system of guaranteed pollution property rights and under ideal “free-market” conditions, society as a whole would get exactly the amount of pollution that its members want—no more and no less.

In a nutshell, Nobel-winning economist Ronald Coase proved mathematically that, with a system of guaranteed pollution property rights and under ideal “free-market” conditions, society as a whole would get exactly the amount of pollution that its members want—no more and no less.

For example, if individuals were granted a “property right” to be pollution-free, then some would be willing to accept cash payments in exchange for allowing a little bit of pollution; and ultimately, after lots of pollution trading, “the market” would decide on how much pollution society as a whole could tolerate. Conversely, if polluters are given the “right” to pollute, then people who wanted to be pollution-free would pay the companies not to pollute—and once again, the market would “decide” how much pollution members of society are willing to pay to prevent. (Remember, I’m just describing this idea, not endorsing it.)

Now, you might think that the level of pollution that society would decide on would depend on how “pollution rights” are distributed—that is, whether polluters are given the “right” to pollute, or potential victims are given the “right” to be pollution-free. But Coase’s theorem shows that, under ideal circumstances, the way that “rights” are assigned doesn’t actually affect the environmental outcome. Instead, for any given set of individual preferences and costs, a pollution market will always wind up allowing the same level of pollution, regardless of whether the polluters or the victims are assigned the “rights.”

And that’s why free-market environmentalists pay so much attention to Coase: his theorem suggests that, if you really want to figure out the “socially optimal” level of pollution—the exact level that free people are willing to tolerate, based on the actual costs and benefits of pollution control—all you need to do is create pollution rights, stand back, and let the market sort things out.

A long line of critics have conceded Coase his mathematical insights, but questioned their relevance. After all, the ideal conditions envisioned by Coase—with firmly enforced property rights, fluid markets, and zero transaction costs—are nearly impossible in practice.

But Hahnel and Sheeran go several steps farther, building the case that Coase’s theorem is even more deeply irrelevant than previous critics have allowed. Here’s the nickel version of their critique:

- Complete information is impossible: One of the key assumptions of Coase’s theorem is that all parties in a pollution market must be essentially omniscient, aware of all private individuals’ preferences to be pollution-free, as well as the costs of pollution control and the potential profits and losses for private firms. That kind of omniscience not only goes beyond what’s realistic, it even exceeds the assumptions of other areas of economics—which tend to assume that economic actors are merely “self-aware” rather than omniscient.

- Without complete information, Coase’s theorem breaks down: Coase’s math suggests that there’s a single “socially optimal” level of pollution that any set of free negotiations will achieve. But once participants in a pollution market start playing their cards close to their chest—say, by claiming that pollution controls will put them out of business—then all bets are off. All sorts of different pollution levels and prices could result from pollution negotiations, depending on how the market plays out under conditions of incomplete information. And that dashes all hopes for having market forces discover a single “socially optimal” level of pollution.

- Coasean negotiations aren’t markets: To achieve mathematical rigor, Coase simplified pollution negotiations to the simplest case: one polluter and one victim. But with just two parties, you don’t have a market at all! Instead, you’ve got a bilateral negotiation, also known as a “divide-the-pie” game. And with those kinds of games, many different price and pollution levels are possible, depending on the specifics of how the negotiations are conducted. Hahnel and Sheeran quote fellow economist Joseph Farrell to explain: “if bargaining and negotiation are perfect (that is, produ

ce perfect outcomes) then the outcomes are perfect. [But] actually, negotiation is far from perfect, even in the simplest situations.”

- Multiparty negotiations make things even more complicated: Standard discussions of the Coase theorem point out that multiparty negotiations can increase “transaction costs”—i.e., costs for running parallel negotiations, or for deciding which people are genuinely victims, and to what extent they’ve been harmed by pollution. But even more troublesome, multiple parties create a host of “tragedy of the commons” complications which make it nearly impossible to believe that market forces alone will arrive at the “socially optimum” level of pollution, with many firms or private individuals “free riding” on the more virtuous actions of their neighbors. Hahnel and Sheeran argue that multiparty problems are so severe that they can’t be simply explained away as higher transaction costs.

All told, Hahnel and Sheeran build a substantial case that Coase’s theorem has very little to do with the actual workings of real-world pollution markets. Absent other democratic institutions and meaningful oversight, “free” pollution markets quite likely would allow far more pollution than people actually want. And if you buy this line of reasoning, you have to demote the Coase theorem from one of the pillars of an entire world view to a quirky but not particularly relevant bit of theoretical math.

Now, I’m sure that a single paper won’t be enough to shake free-market environmentalists’ faith in their ideology. But for those who aren’t already committed to that faith, Hahnel and Sheeran give every reason to believe that free-market environmentalism is like so many other “isms”—beautiful and elegant on paper, but so divorced from reality that it offers very little to recommend itself in practice.

Photo courtesy of flickr user Steve Rhodes, distributed under a Creative Commons license.

Comments are closed.