A while back, we heard that Americans increasingly believed that news coverage about climate change was exaggerated. That seemed bad. Now we hear that news coverage is simply going away. That could be even worse!

It’s a trend that bodes ill for already meager levels of public concern about global warming. Why? Because even if coverage doesn’t change peoples’ minds about a certain topic, it does seem to impact issue salience—or whether people think something’s a big deal or not.

So, less news coverage = less concern.

Analysis by DailyClimate.org and by Max Boykoff at the University of Colorado shows a sharp decline in both World and US news coverage of climate change. Daily Climate editor Douglas Fischer writes, “media coverage of climate change in 2010 slipped to levels not seen since 2005.”

Apparently, after spiking in late 2009 in the run-up to the much-hyped United Nations climate talks in Copenhagen and the release of private emails from climate scientists stored on a English university server, coverage has become startlingly scarce.

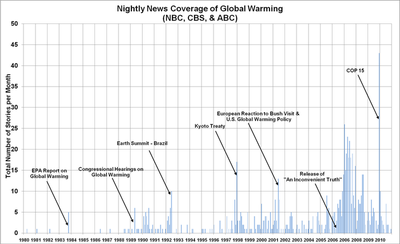

Drexel University professor Robert Brulle has analyzed nightly network news since the 1980s. Here’s his chart:

Andrew Revkin at his NYT blog Dot Earth quotes Brulle at length:

I think it is fair to say that the cycle of media interest in climate change has run its course, and this story is no longer considered newsworthy. Since we know that public opinion is heavily influenced by media coverage, this would imply that public concern or issue saliency of this issue would decline.

Media coverage doesn’t necessarily tell people what opinions they should have on a given issue. But it does influence what individuals are concerned about. So a decline in media coverage of an issue decreases its overall importance and standing on the public agenda. I think the polls pretty much bear this out. If you look at the Gallup most important problem data, the environment was seen as the most important problem by 5% of the population in January 2007. For the last 4 months of 2010, the percentage mentioning environment as the most important problem has remained steady at 1% or less. So while polls may reveal a significant proportion of Americans concerned about climate change, it is not an important issue in comparison to all of the other concerns.

What’s more, as Matthew Nisbet of Big Think and American University, points out, climate change doesn’t fit well into “good” news stories:

As Cornell’s Katherine McComas and Boston University’s James Shanahan note in an oft cited paper, journalists’ coverage of climate change is driven by the need for dramatic storytelling and novel narratives. Much of the drama in news reporting generally—and in science reporting as well—derives from visible political conflict, personality clashes, and contested claims over risks that allow journalists to construct a “news saga” that they can cover for more than a day or week.

Limited carrying capacity and the narrative needs of journalists have fueled what economist Anthony Downs described as “up and down” cycles of attention to climate change.

One could argue that the flurries of reporting on melodramatic side-stories like the ones surrounding “climategate” hurt more than they help. But, visibility is visibility.

Revkin, for one, doubts that media coverage—in any amount—and its impact on public opinion will be the driving factors in shifting energy norms or pushing policy forward in time. He may be right, and I don’t think he’s arguing that public opinion is meaningless. In any case, the “out of sight, out of mind” problem inherent to an abstract and seemingly distant challenge like climate change is only made worse by diminishing coverage.

Network news data courtesy Robert Brulle, Drexel University.

Comments are closed.