For experts in energy efficiency financing, what you’re about to read is going to seem oversimplified. But I invite you to elaborate, correct, and enhance the post in the comments section. (After all, when it comes to blog posts, the comments are as important sometimes as the post itself.) Also, right up front, I should say that interest rates are low for most kinds of loans. Plus, a highly motivated homeowner bent on making all the efficiencies she could to her home would also be able to get tax credits and rebates at least from the federal government not to mention extra dollars from lower energy bills.

For experts in energy efficiency financing, what you’re about to read is going to seem oversimplified. But I invite you to elaborate, correct, and enhance the post in the comments section. (After all, when it comes to blog posts, the comments are as important sometimes as the post itself.) Also, right up front, I should say that interest rates are low for most kinds of loans. Plus, a highly motivated homeowner bent on making all the efficiencies she could to her home would also be able to get tax credits and rebates at least from the federal government not to mention extra dollars from lower energy bills.

So why aren’t people borrowing in droves for energy efficiencies? Part of it has to do with low energy prices—people aren’t spending a big enough chunk of their paychecks on their utility bills to spark large-scale efficiency investment. Some of the other reasons have to do with a market that has not created the right financing products for efficiencies. For some of the reasons I’m going to elaborate on, there isn’t a lot of demand or supply for energy efficiency loans. That’s why we need to consider some big shifts in policy to stoke the market.

I’m going to err on the side of over-simplification here because, too often, energy efficiency advocates over complicate their message. Now, finance is complex, which is why people go to school to learn how to do it, but when it comes right down to it, the basics are really just about borrowers and lenders. That’s what we need to keep in mind to successfully change policy. So I’m going to sketch out with conceptual stick figures why I think generating large-scale demand for retrofits in the Northwest requires government intervention and, in the case of Washington, game changing Constitutional change.

The Borrower. Let’s start with a borrower. A borrower has needs that, if they were met, would improve his overall financial well-being. What he’s missing is the capital—the cash—to meet those needs. So he wants to borrow cash for a reasonable fee, to take advantage of whatever opportunity is on his horizon. Of course, the borrower may have financial liabilities (like existing debt) or assets (like property) that would affect the terms of a loan.

The Lender. A lender, on the other hand, has capital—and sometimes lots of it—usually from other people who have given it to her to invest. The lender’s problem is that in order to return the money to her investors along with some financial gain, she has to find borrowers who need to use the money, and who can pay the money back with interest. She will calculate how much interest she charges to a borrower based, in part, on the risks presented by the borrower: the higher the risk, the higher the interest charge; and the lower the risk, the lower the charge.

Borrower and Lender Meet. Ideally, our borrower and lender meet in the market place and strike a deal. The borrower explains his needs, gives his financial history—he’s borrowed money and paid it back before—and his liabilities and assets. He and the lender negotiate an interest rate, and if the risk is low enough, then the interest payment will likely be low enough for the borrower’s needs, and both parties are happy. The borrower gets the cash he needs at a rate and timetable he can pay back, and the lender generates a return for her investors. It’s a beautiful thing.

The Market Fails. But sometimes the borrowers and lenders fail to strike a deal. Perhaps the borrower is too risky. Maybe he has other debt, which means that the lender might have to wait to get paid back if the borrower runs into tough times. Or maybe the financial benefits the borrower is hoping to achieve are less feasible because of the interest being charged by the lender. When lenders feel a borrower is too risky, the “price” of the money she lends out—the interest rate—goes up, which makes the loan less attractive or even impossible for the borrower.

Borrowing for Energy Efficiencies. These basic rules apply to the energy efficiency financing market place too, especially in the residential world. Homeowners might want to avail themselves of the financial benefits of retrofits, but they often don’t have the cash to make the improvements. It’s in their best interest to borrow money, yet right now borrowing for retrofits isn’t happening the way it is for things like cars or other household products. Why is that? Part of it is that not many parties are fully aware of the financial benefits of retrofits. But a big part of it is also that risks are too high for lenders, which in turn makes borrowing too expensive for borrowers.

Right now when borrowers and lenders meet in the market place they aren’t connecting on energy retrofits, at least not often enough. This is unfortunate because retrofits can be highly beneficial to homeowners (saving money on energy bills over time, for example), but also beneficial to the rest of us: they help reduce demand for scarce energy resources, trim our carbon emissions, and even create jobs in the energy retrofit sector. So what can we do to make the market work?

Finding a Third Party. Based on the simple sketch above, there are three things that would help borrowers and lenders get together to make more retrofits happen.

First, we might help reduce risk, which would make interest rates lower, and might therefore generate more attention from homeowners. A third party could assume some or all of the risk of private loans or make them outright for a low interest rate.

Second, borrowers could get help paying the loans, which would lower the costs for homeowners. If a third party helped cover the interest payments, energy retrofit loans would be more attractive to potential borrowers.

Third, some entity with good credit and lots of money could enter the lending market, making direct loans for energy efficiency retrofits—and make them affordable regardless of the risk.

I’d argue that a third party—with a broad mandate and strong interest in getting lots of residential retrofits done—is just what the energy efficiency financing marketplace needs right now. But what kind of third party has as its mission the public benefit? How about lots of access to capital and outstanding credit? Hmmmm…

The Role of State and Local Government. How about state and local government? State and local government have an interest in the broader public benefits that come from energy efficiencies. And they have capital, and excellent credit.

One obvious objection to local government playing the third party role is that budgets are tight right now. And yes, budgets are tight. But so is the job market. Making energy efficiency loans, or backing them up, will go a long way toward job creation and saving money for working families that they can plug back into the economy. It’s basically an economic development strategy, and it’s what cities, counties, and states strive to do in good and bad times.

You might even think of energy efficiency lending as a stimulus plan for the local economy. In any event, local government is obligated to the public benefit, a much wider mandate than the private banks that aren’t now creating a vibrant lending market for energy retrofits. And because of their broad mandate, state or local government could choose to make affordable loans, and could accept the risk of a higher default rate, effectively

paying for some portion of the loans that go bad.

The benefits—saved energy, more money in the pockets of struggling families, local jobs in the near term, and reduced carbon emissions—would definitely be public. Using funding and credit to break open the energy efficiency financing market is firmly within the scope of what government can and should do.

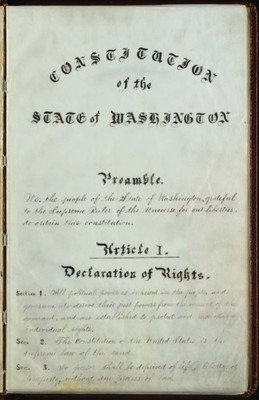

Amending the State Constitution. Unfortunately, in Washington, state and local governments can’t enter the energy efficiency financing market because they are constitutionally prohibited from lending their money or credit to the state’s homeowners who want to invest in efficiencies. (Oregon, by the way, doesn’t have this problem.) As a result, risks for lenders and costs for borrowers remain high—too high to facilitate large-scale investment in efficiency. If we truly want to achieve large-scale energy efficiencies, getting state and local government into the financing market would sure help, especially at a time when the economy is struggling.

In Washington, amending the constitution to allow the lending of state and local money and credit could show borrowers and lenders the value of smart retrofits. An amendment could be narrowly tailored; it might, for example, stipulate that government loans of funds and credit could go only for efficiencies that yield the maximum savings of energy and money, not unlike the requirements of performance contracting. Without more help from government, it’s likely that the energy efficiency market will continue to languish in Washington.

There’s good reason to think an amendment would be a powerful catalyst. Consider what happened when the federal government intervened to lower risks in Whatcom County.

The Community Energy Challenge, a partnership between Sustainable Connections and the Opportunity Council is using federal money to create a loan loss reserve fund. A loan loss reserve fund creates a source of funds to back up loans in case they aren’t paid back. Having protection against defaults lowers risk for lenders and therefore lowers costs for borrowers. The program just recently made its first loan for an energy efficiency retrofit.

In fact, Seattle is now considering using some of its new Energy Efficiency Block Grant for a loan loss reserve fund also so that more loans will be made. Clean Energy Works in Portland, Oregon—where there is no state constitutional problem with lending credit—has perfected a similar model, and has already completed upwards of 60 retrofits. Clean Energy Works also capitalized its loan loss reserve fund with federal stimulus dollars. So there are other ways besides amending the state constitution to pull off the risk reduction that is needed, and the good news is that Bellingham and Seattle are getting started. But turning 60 retrofits into 60,000 retrofits is going to take more than loan loss reserve accounts being set up in two cities. To get those numbers will require bigger changes that will make it easy and affordable to borrow for retrofits.

Sustainable Shift. Amending the constitution to put the state’s credit to work to motivate borrowing and lending for retrofits will create energy savings, jobs, and save families money—all from shifting away from consumption toward conservation. That’s the kind of sustainable shift that would make taking on the political challenges of a constitutional amendment worth it.

Photo credit: Image of the Washington State Constitution from Wikipedia Commons.

.

Marlowe Kulley

Just to clarify, as of mid-August Clean Energy Works Portland has completed over 180 retrofits and has another 250 projects in progress. By the end of 2010 we will have completed our 500 home energy-efficiency retrofit pilot, which will inform the scale up of our program throughout the state of Oregon. Clean Energy Works Oregon has a goal of 6,000 home retrofits over the next three years.-Marlowe KulleyClean Energy Works PortlandCity of Portland Bureau of Planning & Sustainability

Alex Ramel

Thanks for your continued coverage of this important issue Roger. As you know, last legislative session a bill was proposed to create a work around to the constitutional barrier by creating energy efficiency utilities which would define the public benefit of local government helping privately owned businesses save energy through EE lending. The lawyers all agreed that this would get around the constitutional prohibition, but the banks were opposed to it because PACE style financing puts part of the outstanding debt(any currently due or past due property taxes) in a position in front of existing mortgages in the event of default. With that issue unresolved, the bill died in committee. It only took the rest of the country a little bit longer to notice that issue, and now PACE financing is on hold all over the country while the question of do these end up looking like home improvement loans that become better-than-first-position mortgages gets addressed. In your estimation, is working on the constitutional amendment a high priority given that even if we got it, the federal financial regulators might still tell us we can’t do PACE like lending? Alex RamelSustainable Connections

James Irwin

@Alex – One of the best things about a constitutional amendment like this would be that the money would be originating from state or local governments via (most likely) a bond issue – and local governments wont necessarily have the same hangups about lien position as the banks do. If a municipality were willing to accept second lien position (and if they believe this is a good investment, they’re likely to), then they don’t run afoul of FHFA. Since they’re already able to access cheap capital, the secondary lien position shouldn’t affect the overall cost of borrowing. Another benefit of having the capital originate from state/local government is the possibility of using other mechanisms to secure the assessment – a municipal water bill, for example. This carries a range of other benefits as well, not least of which is the possibility of reaching the rental market (which you can’t get to with PACE).

Roger Valdez

Thanks for the question Alex, the answer James, and the update Marlowe. James is right, and points out succinctly a couple benefits of expanding the role of local government through an amendment I didn’t mention: on bill and the ability to accept second position. The simple fact is that there is no large demand for retrofit financing. Stoking that demand is going to require a lot more than cheap loans, even though affordable financing is necessary if not sufficient for achieving that outcome. Tying the hands of government only adds more grade to the steep hill we have to climb. While I think Clean Energy Works is the best thing going in terms of energy financing programs (and Whatcom County is emerging quickly as well) 180 retrofits is still a long way from where we need to be. Oregon has no constitutional limits, and the Energy Challenge in Whatcom is getting started in spite of the limits in Washington. But we’re a long way from where we need to be. Politically, it is only slightly more challenging to amend the constitution than to try to get to get some pale, attenuated form of PACE, especially now when PACE itself is essentially dead, and maybe for good reasons(see Aaron Berg’s column on this topic at Sustainable Industries here. PACE isn’t necessary to achieve what we’re looking for and it’s probably time to move on. But reducing risk and costs are still necessary. Getting government in that game is part of that. And, as James points out, on bill is really a way of simplifying monthly payment as much as anything else. I would argue that explaining and passing an amendment out of the Washington State legislature might be easier than a 7 or 8 page bill (with all kinds of limits to appease community banks and utilities) that confuses advocates and legislators alike. It’s simple: let local government make loans of credit and dollars to help families save energy and money. The Community Energy Challenge and Clean Energy Works have created the proof of concept. Now it’s time to back a scaled up program modeled on those success stories.