Do people notice small changes in gas prices? I’ve been wondering about this lately—which gave me an excuse to download historical gas price data—and I learned a couple of things in the process. Consider:

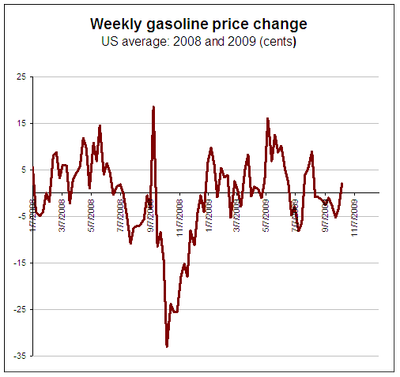

Gas prices changed by 7 cents per week, on average, during 2008 and 2009. Sometimes prices went up and sometimes they went down, but they rarely stayed constant. What’s more, the price changed by very different amounts each week.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Much of the most intense volatility occurred during 2008 when gas prices broke the $4 barrier and then subsequently collapsed as the economy unravelled. But even in 2009, gas prices are changing 5 cents per week, on average.

Is 5 cents a lot? The answer depends on what you mean.

Five cents is a lot historically. From 1993 through the end of 2007, gas prices changed by just 2 cents in an average week. Expressed as a percentage of gas prices, the average weekly price change represented less than 1.4 percent of the retail price of gas during that period (when gas prices were much lower). In 2009, by contrast, the 5 cent weekly change represents 2 percent of the retail price.

Five cents is also a lot, I think, in the context of recent policy proposals. The modest carbon tax proposed by the conservative Washington Policy Center would work out to roughly 3 cents per gallon of gasoline. The most recent gas tax increase in Washington—the hotly contested “nickel” tax of 2003—was, of course 5 cents. In Oregon, there’s a big to-do about whether to raise the state gas tax by 6 cents. And this year, Idaho’s legislature rejected a 2 cent tax increase. In other words, when we talk about gas tax increases, we’re mostly talking about pretty small sums of money—less than the weekly average price change.

What’s interesting to me is that it’s not entirely clear that consumers would even notice such small price increases. (That’s a different question, by the way, than whether consumers would be affected by the price increases.) For example, consider what would have happened to gas prices if the Washington legislature had passed ESHB 1614 last year, a bill that would have added at most 3.5 cents to the price of gasoline to fund Puget Sound cleanup.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

In case you can’t tease this apart, the red line shows actual gas prices during 2008 and 2009; the green line shows a hypothetical price if a 3.5 cent fee had been added starting in January 2009. (The price, however, is a US national average, while the fee would have been specific to Washington.) As you can see, there’s not a huge difference between the two scenarios.

I’ve argued before that gas prices have a bigger effect on consumption than we think. But I’ve also argued that not all gas prices are equal. It appears that for a price increase, such as a tax, to reduce consumption the change should be big enough to notice and—just as important—the price increase shouldn’t be used to increase consumption. So there’s probably a good debate to have about whether 3.5 cents per gallon would be enough to affect consumption, given that every week the price of gas changes by 5 cents per gallon on average. My hunch is that it wouldn’t make much difference: it wouldn’t impact consumers in a serious way and it wouldn’t dent oil company profits (in part because oil companies just pass on price increases to consumers).

Needless to say, however, reducing gasoline consumption is hardly the only purpose of a fee or tax on petroleum products. State gas taxes are generally used to build and maintain highways. Other fees are used to clean up pollution. But insofar as we want to affect consumption with prices, my guess is that the price change would have to be outside the “noise level”—the ordinary fluctations we see every week — to have a significant impact. Discuss.

Jon Morgan

Didn’t the national transpo policy and revenue commission recommend a 40 cent increase in the federal gas tax? That needs to be raised substantially, with rebates to low-income people like Canada does. We need tolling and VMT taxes too, but if we’re to raise the funds not only to sustain the highway trust fund but to create a permanent, dedicated transit funding source (which we should), the gas tax has to be much higher. Pennies and nickels are nothing indeed—you can find more variation than that between different gas stations within a mile or two of each other. I’m sure people notice, but I can’t see 5 cents a gallon reducing consumption. Ten cents a gallon per year for 5 years (Ross Perot’s 1992 proposal!) would make a real dent.

Oregon Michelle

Plus, the cheaper something is (like gas) the more you waste it; while, the pricier something is the more you conserve it.Substantially raising the price of gas seems to be the only way that people will value it more highly and use it more wisely.

eldan Goldenberg

I have heard (possibly from a previous Sightline post, come to think of it) that there is a huge difference between the demand elasticity of a short-term price change versus one that is seen to be persistent. In other words, n cents of additional tax are likely to have a bigger effect on driving than n cents of price spike because Ahmadenijad gave an aggressive speech.I don’t know if there’s data to bear this out, but it does make intuitive sense, given that a lot of the average household’s driving is difficult to dynamically substitute out, but a long-term change in driving costs will alter peoples’ choices of where to live and work.

Jon Morgan

Yes, I think Eldan is absolutely right. As much as people complained about $3 gas 18 months ago, their driving habits didn’t really seem to change until they perceived (backed up by loads of polling) in the summer and fall that “high” gas prices were here to stay. THEN we started seeing the first VMT decrease since 1979 and flatter or falling demand (which, lo and behold, relieved a little pressure on gas prices). Even now, gas prices haven’t fallen all the way back down; in urban Seattle I see them just under $3 a gallon. Yet transit has kept most of its ridership gains; what it’s lost may be due exclusively to job losses. I think it was the US Chamber of Commerce that wrote in the Washington Post a few months ago that now is exactly the time to impose a 40-50 cent per gallon gas tax increase. Part of their argument, divorced from environmental concerns, was that we need to use less gas to shrink our trade deficits since it’s imported. Combine that with the national security vulnerability of relying largely on Middle East nations we don’t like so much for oil, and you’d think a chunk of Republicans would join most Democrats in doing something like this.

Jon Morgan

I can think of 3 general levels of response to gas prices as they rose in 2008. There may be more, especially if they get higher than last year’s peak. But my off the cuff observation:1st level – Simple habit changes ($2.50-$3/gallon). keeping tires inflated, more searching online for the lowest gas prices, consolidating trips, trying to use the more/most efficient car in the household for the longest trips, more interest in hypermiling.2nd level – Vehicle changes ($3-4/gallon). buying more efficient cars, leaving guzzlers parked most or all the time, sometimes even selling them. More interest in walking, biking, motorcycles, scooters, carpooling/ridesharing, and transit. More interest in hybrids, alternative fuels, electric cars. Questioning reinstatement of national speed limit.3rd level – Location/distance changes ($4-5/gallon). Less willingness to commute as far to work. Transportation factoring more heavily in deciding where to live, work, or locate jobs. Transit and dense urban real estate spike. Car dealers see sales drops so steep some have to close, and no one can unload an SUV. Exurban “drive til you qualify” real estate drops badly (this is where the bulk of foreclosures are as CEOs for Cities reported). Strong public outcry against $4 gas, but also for walkable places and good transit. Mass Transit Now passed easily, along with almost all transit issues on the ballot (St. Louis being the one big exception). If this price range were more sustained, we might see builders unwilling to keep producing sprawl and more interest in infill development, even in cities with bad or no growth management. It might take $5-6 gas for real pressure to spend more on transit and less on roads at the federal level. (God I want the transpo bill done before the 2010 elections!)

Jan Steinman

Chaotic price volatility is characteristic of resources whose demand is close to supply. Both are relatively inelastic, and that causes wild gyrations.Donella Meadows (et. al.) predicted this nearly 40 years ago!

niall dunne

Eric, I don’t really get the point of the second graph. If the y-axis increments were smaller (e.g. 5 cents instead of 50), wouldn’t you “notice” more of a difference between the red and green graph lines?

Eric de Place

Niall,Not really. What makes the difference appear small is not the increments on the y-axis but rather the relative size of 3.5 cents compared to the total height of the y-axis. Charts are extremely easy to manipulate for visual effect, but I think this one does make a fair point. A 3.5 cent difference (between the red and green lines) represents less than 1.5 percent of the current price of gas and less than 1 percent of the price of gas in mid-2008. It’s because the percentage difference is so small—because there’s very little difference in “real life”—that the lines can barely be distinguished.

Daucilous Sadala

I am a a fourth year university Economics student looking for data on fuel prices to use in my dissertation for. I would want to have data on annual world fuel prices (USD/gallon)from say 1970 to 2012. I have tried several sources to no avail.

I wonder if you could help me on that.

Desperate student.