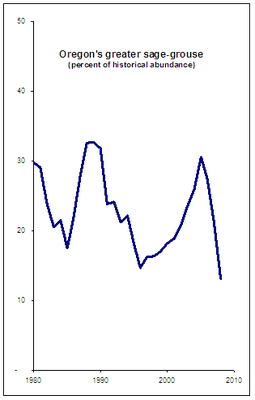

As part of the Cascadia Scorecard‘s wildlife indicator, Sightline monitors the populations of five Northwest species as a proxy for broader ecological health. We track the population of greater sage-grouse in Oregon, which can tell us something about the integrity of the region’s sagebrush country. Unfortunately, recent population trends are troubling: biologists believe there are now as few sage-grouse in Oregon as at any time since they have been studied.

As part of the Cascadia Scorecard‘s wildlife indicator, Sightline monitors the populations of five Northwest species as a proxy for broader ecological health. We track the population of greater sage-grouse in Oregon, which can tell us something about the integrity of the region’s sagebrush country. Unfortunately, recent population trends are troubling: biologists believe there are now as few sage-grouse in Oregon as at any time since they have been studied.

With the Northwest’s abundant iconic scenery, it is easy to ignore the vast swath of interior desert of southern Idaho, eastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. That’s unfortunate because the “shrub steppe” ecosystem—it’s not technically a desert—is home to an astonishing array of wildlife, some of which inhabit no place else on earth but the arid Northwest. In fact, the region is home to curiosities like pygmy rabbits and giant earthworms, but also a full suite of more “charismatic” critters like elk, owls, porcupines, cougars, and of course, the sage-grouse.

Perhaps no single species speaks for the health of sagebrush country as well as the greater sage-grouse, a bird that is best known for its ostentatious breeding displays. (Check out this video to see what I mean.) The birds can serve as a rough indicator of the health of their ecosystem because nearly every form of human activity in sage country affects their populations. Fencing, towers, and transmission lines give their predators the advantage. Resource extraction, such as mining and drilling, stress the grouse and render land unsuitable for mating and breeding. Farmlands and sagebrush eradication destroy their habitat conspicuously, while livestock grazing and off-road vehicles accomplish the same end more subtly. Invasive species, especially cheat grass, render their landscapes more vulnerable to fire even while simplifying the native plant communities, making food more scarce. And long-term mismanagement of the land can turn even native species, like juniper, into a threat.

Sage-grouse are now under consideration for listing as a federal endangered species in the United States. (A decision is expected by summer of 2009.) And if the future of sage-grouse is in doubt, then it is probable that the integrity of the large sagebrush ecosystem is also severely weakened, boding ill for a number of plants and animals.

During much of the last decade, Oregon’s sage-grouse populations appeared stable. While their numbers follow a natural cycle of ebb and flow, biologists have largely believed that their current numbers reflected population stability. Unfortunately, sage-grouse numbers have recently dipped significantly, in part because a serious drought that afflicted eastern Oregon. At last count, biologists estimated that only about 22,000 sage-grouse remain in the state, roughly 13 percent of the bird’s historical abundance.

While the bird’s short-term trends are concerning, their longer-term prospects may be jeopardized by what is now only a minor culprit. Rising temperatures have been blamed for the expansion of mosquito-borne West Nile Virus into the Northwest, a disease to which sage-grouse appear extremely susceptible, dying in virtually every instance of exposure. If climate change increases the presence of West Nile, or if it abets the expansion of other similar diseases, then it may ultimately spell disaster for local sage-grouse populations. Warming temperatures and altered rainfall patterns may also magnify the wildfire danger posed by the spread of cheat grass.

One of the ironies of sage-grouse conservation is that the birds are threatened by the effects of climate change as well as by some of our best solutions to climate change. Renewable energy projects, a boon for our electricity systems and rural economies, may further degrade sage habitat. Wind turbines, for example, can mean new roads, transmission lines, and other development in sensitive habitat. (See, for example, page 96 and following of this US Fish and Wildlife Service report.)

If there is hope for Oregon’s sage-grouse—and for sagebrush ecology in the Northwest more generally—it depends on our ability to promote conservation projects in the arid interior landscapes that are often overlooked. Oregon has developed a working conservation plan (pdf), one that may get a boost if the bird wins approval for listing under the US Endangered Species Act. And in recent good news for sage-grouse, the US Bureau of Land Management has committed several million dollars of federal stimulus funds to habitat restoration in Oregon.

On public lands, one promising model may be the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge in southeast Oregon where cattle ranching has been banned and where volunteers have removed miles of old fencing, helping to return the landscape to its wild integrity. On privately-owned lands, other voluntary conservation efforts may hold some promise. But over the long term, the health of sage-grouse may depend on arresting climate change before its effects become too severe.

Want more on sage-grouse? I don’t blame you! Check out these resources from the Audubon Society and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Find more on sage-brush ecology and conservation at the Sagebrush Sea campaign, and the Oregon Natural Desert Association. Photo is by Gary Kramer, US Fish and Wildlife Service.