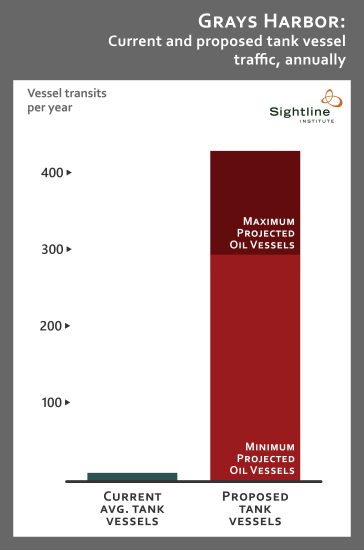

Three large oil terminals proposed for Grays Harbor could undermine the region’s economy and local culture. That’s the takeaway from two recent economic analyses: first, a study on coastal recreation in Washington from the Surfrider Foundation and marine technology firm Point 97; then, Economic Impacts of Crude Oil Transportation on the Quinault Indian Nation and the Local Economy, published by economic consulting firm Resource Dimensions.

These reports help clarify the real threat that oil transport poses to Grays Harbor. But since most people don’t have the time to thumb through such detailed findings, Sightline commissioned the following graphics to sum up the key points.

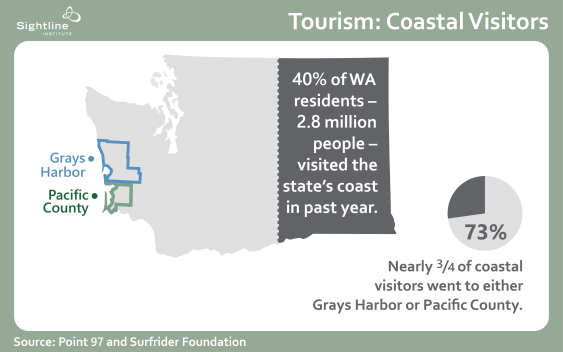

Over forty percent of Washington residents travel to the coast each year; their top recreational activities are beachgoing, scenic enjoyment, wildlife viewing, photography, and hiking/biking.

Coastal visitors spend an estimated $481 million dollars per year on recreation and tourism trips. An oil spill in the bay could do tremendous harm to businesses that are dependent on tourism dollars.