As I argued in part II, electric bikes could be forerunners for electrifying the whole transportation sector. They’re sweeping into urban areas in China by the tens of millions. New technologies are improving e-bike performance. And powerful institutions are aligning to speed battery innovations.

As I argued in part II, electric bikes could be forerunners for electrifying the whole transportation sector. They’re sweeping into urban areas in China by the tens of millions. New technologies are improving e-bike performance. And powerful institutions are aligning to speed battery innovations.

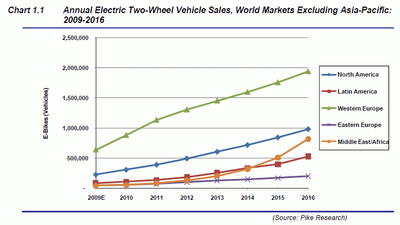

Many observers now believe e-bikes will grow rapidly in North America, including in the Pacific Northwest. Colorado-based market analysts Pike Research, for example, predict that US sales will quadruple from 250,000 e-bikes in 2010 to more than 1 million in 2016, as shown in the chart below. (Asia is left off the chart, because it’s on a different scale. Some 98 percent of e-bike sales worldwide have been in China.)

To speed this process, one common approach—evident in the bevy of tax credits available for purchasers of hybrid and electric cars—would be to subsidize e-bike sales. That’s what Santa Cruz, California, did early in the 2000s decade. Coupons from local authorities helped sell as many as 1,000 e-bikes there, making it briefly the e-bike capital of North America. Similarly, rebates from Swiss localities have boosted e-bike sales in Switzerland. Some 16,000 sold there in the first half of 2009, according to one report.

The implicit assumption behind underwriting new products with public funds is that once they are adequately established in the marketplace, they will spread contagiously without continued public support. The public investment is justified by the subsequent flipping of a market, in which cleaner, greener products push out dirtier products and yield large benefits for society.

This assumption may be reasonable for green products that are new and unfamiliar, such as ground-source heat pumps and green roofs, or that are not produced on a large enough scale to bring down manufacturing costs. But electric bikes are neither new nor unfamiliar: half a million have sold in the United States over the years. And they’re a variation on the ubiquitous bicycle, which is found in a majority of homes. What’s more, we should have already benefited from the economies of scale, insofar as they’re rolling out of Chinese factories at a pace of 20 million a year, far in excess of the scale of US auto manufacturing before the recession. Furthermore, the notion that there is a tipping point for sales of e-bikes is speculative at best. In fact, a look at electric bikes’ progress in North America and abroad leads to the conclusion that they confront a formidable set of barriers to growth—barriers that public sales rebates are unlikely to overcome. I’ll describe these barriers in my next post.

Read part four of this five-part series, “Circuit Breakers.”

Photo of charging electric bicycles courtesy of Flickr user lmnop88a under a Creative Commons license.

steve

I’ve been reading this series with some interest. One of the major problems is the perception of what a bike is – electric or not. In the US you have roughly 1% of the population who use bikes for real transit even though most homes have at least one bike. There are many reasons for this, but the bottom line is perhaps a few percent might be interested in a bike for real transport and the remainder are convinced they aren’t practical – probably more for infrastructure reasons than physical effort.The hard core see ebikes as a lame way out. Many laugh at anyone who rides one (I’ve seen that in Portland and other places)In China a huge number of people can’t afford cars or large gas powered motorcycles. An ebike is a step up from the bike as it extends the effective range of a person at a practical price. In the US a bike or ebike is seen as decreasing mobility at a price ($ and time), even if that doesn’t hold up in urban areas.Europe is seeing an increase in ebike use as ebikes are a variation of something that is already acceptable.The only way to make ebikes popular here is o improve infrastructure and public attitudes towards bikes as transit. The bike needs to move beyond toy status.I was involved in a survey that looked at usage patterns of ebikes. For bikes that cost under $1000 (mostly Chinese imports) , self reported use a year after purchase had dropped dramatically. Dissatisfaction was high and the root problems were more with bike infrastructure than with the ebike.

Greg Tuke

Alan, there are some big differences in e-bikes, and some, like those selling in China, are a step backwards. We need to be promoting ebikes that combine the best of human power with the supplement, when needed, of a shot of electric power assist. While this still does not deal with your larger point, that being that we absolutely need a dramatically improved roadway system to support bikes (Holland being one prime example of this), it does make it clear that we are not just trying to get folks on cheap electric “scooters’ which is what China now has. There is virtually no human power put into these when you ride. Thank you for your great articles on this topic. I am appreciating them alot.