Editor’s note: A revised and updated federal version of Sightline Cap and Trade 101 is now available. Download Cap and Trade 101: A Federal Climate Policy Primer here.

This post originally appeared June 11, 2009. It was based on the version of the American Clean Energy and Security (ACES) Act (H.R. 2454, or “Waxman-Markey”) approved by the House Energy and Commerce Committee. By June 26, when the bill passed the House and headed to the Senate, it had grown by almost 480 pages. What changed?

Waxman-Markey is 1,428 pages long, so I’d be fibbing to say that I’ve actually read all of it. But I’ve pored over key sections and, though I expected to hate the amendments, I don’t. Most of the changes are benign or immaterial. Few are nefarious. None are deal breakers. What’s more, the tone of much news coverage—decrying the log-rolling and back-room deal making that brought the bill to passage—was wrong-headed, I thought. The “special deals” were mostly things like increased funding for job training programs—not exactly a sign of public corruption or parochialism.

My grade?

Overall, I still give Representatives Henry Waxman of California and Edward Markey of Massachusetts a solid “B.” I’m grading on a curve—the curve of political reality. Straight A’s are hard to come by with oil, coal, and other industries spending almost $80 million lobbying on climate policy in just the past three months (pdf). Under withering fire, Waxman-Markey’s cap-and-trade superstructure remained intact. In fact, the 280-page centerpiece of ACES that covers cap and trade—the part of the bill on which I’ve focused my attetion—has changed little in months. The bill grew by accretion, like a raft to which ever more planks are lashed.

So I’m rejoicing about the bill’s passage, but holding my breath about the US Senate. In particular, I’m hoping that the offset provisions of ACES—already weak in the bill’s version I wrote about before and weakened further in the final act—get stronger in the Senate. Even if they don’t, we can hope that the administration implements the offset provisions in ways that preserve the law’s overall effectiveness. If so, ACES could be the most important piece of energy or environmental legislation in a generation. It’s also much-needed economic policy: clean energy can be the path out of recession.

How do I love ACES? I’ll count the ways as soon as I document its flaws. First, though, a warning: to keep this post short I used some wonk-speak. (An English-language exposition is available in our revised Cap and Trade 101 federal primer.)

6 (+1) things I hate about Waxman-Markey:

- I hate that Waxman-Markey allows 2 billion tons of offsets each year. That’s too many by an order of magnitude. Offsets are too slippery; you can never be sure if you’ve reduced emissions overall or just moved them around. W-M’s offsets provision could blow a hole in the cap—and the cap is the only guarantee we’ll meet crucial goals. This offsets number is, in my view, the bill’s biggest flaw. (Still, W-M is admirably complete in designing a set of administrative rules to sift real from fake offsets. Whether such regulatory standards will be enough is perhaps the key question about the bill, as Lisa argued.)

- I hate that Waxman-Markey’s goal for 2020 is a paltry 17 percent reduction below 2005 levels (19 percent, considering love #3). President Obama’s clean-energy stimulus and budget investments, the 2007 federal energy bill, new fuel-economy standards announced in May, and new programs in Waxman-Markey for efficientbuildings, vehicles, and appliances—these initiatives alone might take the United States to a 17 percent drop in emissions. Even without cap and trade.

- I hate that W-M only auctions 15 percent of permits at first. Carbon permits will be a public asset ultimately worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Distributing them for free, even distributing them for free with as much integrity and cleverness as W-M does, is at best sleight of hand. Sooner or later, voters will understand that permits are cash in another form. A more forthright policy would auction all permits first, then distribute the money in the light of day. If coal and oil companies really deserve billions of public dollars (see hate #6), let them argue for it in the halls of Congress, with the news cameras rolling.

- I hate that W-M gives 15 percent of permits for free in its early years to energy-intensive companies in traded sectors. Transitional assistance for traded industries is a legitimate public objective, but handing out permits is too blunt a tool. “Border adjustments” or “carbon tariffs” would be the better policy tool.

- I hate that Waxman-Markey, having just lavished 15 percent of permits on energy-intensive firms, dedicates a fraction of one percent of permits to programs that benefit workers. It gives 0.5 percent to transitional aid for displaced workers andgreen-collar job training programs. Combined.

- I hate that in its early years, Waxman-Markey gives 2 percent of permits to oil refiners and 5 percent to coal power plants. W-M also hands out permits to pay for carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects at coal plants. CCS is a promising technology worthy of research grants, but it’s too speculative to deserve 5 percent of permits every year, in perpetuity. (And as commenter Jim Lazar pointed out on the original post, the free permits for coal power plants perversely encourages them to continue polluting the atmosphere. Better to give them permits regardless of whether they keep operating than to give them permits contingent upon their continuing to spew carbon dioxide.)

+ 1. A new, extra thing to hate about the amended version that passed the House: I hate that the farm lobby wrote itself special rules so that the US Department of Agriculture is the arbiter of agricultural and forestry offsets in the United States. Offsets hold real potential, but they’re also tricky. Appointing a single agency the official arbiter makes sense, and it ought to be the nation’s pollution-control agency EPA. This amendment was essential t

o winning passage, I understand, and it’s not a deal breaker. But it’ll take close scrutiny from the administration, Congress, and public-interest watchdogs to make sure USDA holds farmers and foresters to the same standards that EPA holds other offset vendors.

7/16/2009 UPDATE: +1 more. The penalty is relatively mild for emitting more greenhouse gases than you have permits for. You have to reduce an amount of carbon in the subsequent year that is equal to your excess. You also must pay fines of two times the prevailing permit price (at auction) per excess ton. At $15 a ton of carbon—a likely price in the early years—the fine would be just $30. The fines for noncompliance in the US acid rain program are far steeper: an excess ton of sulfur dioxide brings a $2,000 fine. (Hat tip to Andrew in Chicago for this point.)

14 things I love about Waxman-Markey

Enough bad news. There’s more to love than there is to hate:

- I love the 2050 goal: a reduction of emissions by more than 83 percent below 2005 levels. Beyond carbon in 40 years!

- I love Waxman-Markey’s scope. It is comprehensive, covering essentially all fossil fuels, along with most other greenhouse gases. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that W-M’s cap would cover 86 percent of emissions by 2020. For uncapped emissions, such as those from landfills and animal farms, it offers regulatory standards and other programs.

- I love W-M’s “strategic reserve”—a stockpile of permits that authorities will accumulate to help buffer prices. To establish the reserve, authorities will withhold a share of each year’s permits, typically 1- 3 percent. The reserve will have the effect of tightening the cap in normal years, but if permit prices spike upwards (rising by 60 percent above their three-year average), it will temper the market by releasing permits. Smart policy! This reserve is a clever, cap-protecting alternative to an off-ramp, which would generate cap-busting extra permits if prices spiked.

- I love that W-M operates (mostly) upstream in the energy economy. “Upstream” simplifies everything and makes the cap more comprehensive. It targets roughly 7,400 US companies, including oil and natural gas suppliers plus power companies that burn coal.

- I love that, by 2030, under W-M, federal authorities will auction 70 percent of permits and distribute the remainder to public agencies and institutions. Those entities will sell their permits as well, likely through the federal auction. It’s not 100 percent auctioned from day 1, as it ought to be, but it gets there eventually.

- I love that, from its inception, Waxman-Markey auctions 15 percent of permits for the benefit of low-income families. Working-class households have done the least to cause climate disruption; they stand to lose the most from it; and their pinched budgets are most exposed to the fossil-fuel rollercoaster. The Congressional Budget Office estimates such rebates might be worth $161 for a single adult in 2012 and grow over time.

- I love that, starting in 2026, federal authorities will auction all unallocated permits and distribute the proceeds in equal payments to all legal US residents. By 2030, that’s 55 percent of permits, worth tens of billions of dollars. It’s almost Cap and Dividend, and it will probably make climate policy a pocket-book winner for every family below the median income.

- I love that low-income families will get both their 15 percent climate credits and their per-capita dividends. W-M will compensate them for some of the cruel injustice of climate disruption itself.

- I love many of its technical features: W-M provides for unlimited “banking” but tightly limits “borrowing”; has few barriers to bidding at its permit auctions (low barriers to entry are among the best safeguards against market manipulation); uses quarterly, uniform-price, sealed-bid, single-round auctions (don’t ask); incorporates a battery of protections against market manipulation; allows linkage with European and other cap-and-trade systems, at the discretion of federal authorities; and allows any recipient of free permits to offer them on consignment at the main federal auction. (More on all this here.) (And I love that the amended version that passed the House included even more provisions for oversight and regulation of secondary carbon permit markets.)

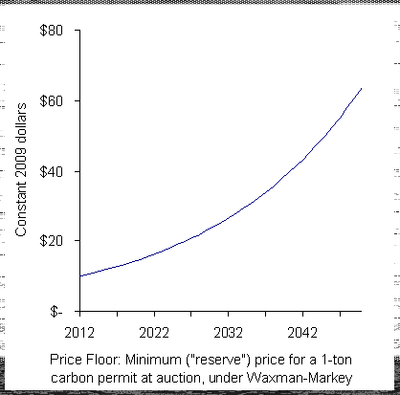

- I love that W-M sets an auction reserve price of $10 when the program begins in 2012. I love that the reserve price will rise each year by 5 percent plus inflation, as shown in this chart. By 2050, permits will never sell at auction for less than $63 (in 2009 dollars). This rising price floor will deliver us to the climate-pricing dream-world I sketched here. In effect, W-M incorporates a carbon tax shift in its cap-and-trade system.

- I love that W-M allocates 10 percent of permits (shrinking over time) to states, to fund renewables and efficiency programs, such as retrofits for all and upgrades to schools and other public buildings.

- I love that W-M dedicates 3 percent of permits to climate-change adaptation—human and natural, domestic and international—and raises this allocation to 12 percent in 2027.

- I love that W-M supports conversion to clean-energy abroad, devoting 1 percent of permits to this purpose initially and 4 percent after 2027.

- I love—or at least feel grudging admiration—that W-M finds ways to give free permits but still channel the dollar value of those permits to families. For example, I hate that W-M gives 30 percent of permits to electric utilities (not to power generators but electricity retailers), but I love that it requires them to rebate the value of those permits—after selling them on the market—to their customers in equal lump-sum payments. This mechanism is less transparent, universal, and fair than auctioning permits and sharing the revenue in equal parts. For one thing, rebates will vary widely, depending on utilities’ fuel mix. For another, utilities have no idea how many people share each meter, nor can they ensure that landlords pass rebates to their tenants. Still, it’s an ingenious compromise that may prevent most corporate windfalls, becaus

e electric utilities are closely regulated. It also ensures that the carbon price signal will still be felt throughout the electricity market.

The “loves” outnumber the “hates” two to one. Among the “hates” only one could be fatal to cap and trade: the overprovision of offsets. Others are annoying, odious, even outrageous, but, considering the power of coal-dependent swing states, not too surprising. In fact, what’s a surprise to me about Waxman-Markey is how good it is as a piece of policy. Hence, I give it a respectable “B.”

Waxman-Markey is the vehicle for a US cap-and-trade system, if the country is to have one in time to reach a new international climate agreement in Copenhagen in December. If the Senate enacts a(n improved!) version of this bill, I predict Canada will follow suit with a harmonized cap-and-trade law within two years. I suspect British Columbia will sign up even before Ottawa (see this story in the Vancouver Sun).

Waxman-Markey will, like any far-reaching and contested legislation, probably emerge from Congress imperfect: Still, as compromised as are some of its provisions (too little auctioning, too loose a cap initially, too much money to unproven CCS, too many offsets), it remains a giant leap toward a clean-energy economy.

All Cascadian eyes should now turn to our US Senators, especially Montana Senator Max Baucus (pictured here), who chairs the Finance Committee and is the second ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee. Both committees, along with the Energy Committee (on which Senators Ron Wyden of Oregon and Maria Cantwell of Washington serve), will have key roles in shaping the Senate climate and energy bill.

newphase75

Great! Thanks for posting an update to this analysis, Alan. I gave props to the original article in one of my blog posts as an example of balanced analysis, and will update the link with this one.Keep up the great, and disciplined, work.Daniel

David

Cap and trade will hurt the poor the most. The carbon offset will be effected in poor countries where large tracts of land will be bought for planting trees to capture CO2. The problem is that there won’t be enough farm land for the poor to grow crops on. Some species of trees may not even be compatible with the local environment. I read how a carbon offset forest in Latin America for some polluting industry in Scotland was depleting the water table for the local farmers. The Australian tea trees consume too much water. They were planted because of studies showing that they sequester large amounts of CO2. Additionally, farmers in the States will have to raise prices for wheat and corn to pay for the carbon taxes. This will make food too expensive for the global poor. Cap and trade is a subtle form of genocide that would exceed the figures for the Nazi and Soviet genocides.

Robert

David I read your comment on cap and trade.

I thought You made a good point, this is just another way to ham string the U.S. economy.That apparently is what the one worlders want, to make other countries look good as far as trade is concerned. That way other countries will be able to sell more of there goods compared to the U.S.. You are right on. It is all

like one big game of who can dominate over us.

Jack

This legislation will kill the domestic energy industry! Is the allocated money for retraining energy workers or just thrown back to energy companies workers?

Jalene

I think that people need to take into consideration the full effects this bill could have on our economy before forming an opinion. This bill will raise gas and energy prices and this bill will cause coal plants to go unbuilt,inturn having a dramatic impact on our natural resources. Bottom line: less jobs for Americans and higher prices for everyday needs and desires. Want to change that, or can your wallet afford this hit? http://tinyurl.com/klfut8

Patrick

Even giving props to the original article did not cause me to leap to a new window and read it. This energy bill, as previously commented by David, Jack, and Jalene, will hurt the lowest on the economic ladder including the lower half of the middle class in the United States. The net effect? Eureka! A two class economic system in the United States like the rest of the world, at last! Whether you agree or disagree is irrelevant. The passage of any form of this bill will be devasting and life changing for all the poor and destitute. The rich won’t just get richer, they’ll get further removed from the rest of the world’s reality.

Michael

Kind of funny how everyone thinks about there own costs or that of the poor. The simple true is we are getting electricity for a very cheap cost , and passing the buck to our kids and grandchildren to clean up the mess we are making. I wasn’t sure where I stood on the Waxman-Markey’s cap-and-trade bill , but the more I think about my kids the more I want this bill to pass ,with teeth.Thank You

Mac Ramsay

The power companies can use any scare tactics they want but the bottom line is they want to keep their stockholders and most of all the ‘big wigs’ happy. To help clean up our planet with the primary start only of the Waxman-Markey Bill will hurt them in their pocketbooks and they will not stand for this. Thus, bringing out all the big guns; the lobbyists. The Waxman-Markey Bill is not the best in the world but it is a beginning!

Steve

I hope everyone who reads this post takes a moment to fully understand that every dime that is required to be paid will be paid for by the consumers. Power companies, manufacturers, builders and the 7400 “companies” must pass along this cost and it will fall directly on the shoulders of consumer. There is no “evil” corporation that must be taxed. There is no possible way that the United States, both consumer and producer, can pay for this. Not given the massive amount of debt we are carrying as a society nor not the amount of taxes that we will soon be paying for the wars, health care reform and the stimulus(es). Give some serious thought and research to the fact that even corporate “taxes” are paid for by the consumer. It is the nature of business to pass along the cost of goods sold and add margin to build “profit”. Even if you tax “profits”, the underlying strategy is to maximize margin. Please wake up and see cap and trade as nothing more than a giant, derivative-generating, federal bureaucratic nightmare. There are far better ways to move this country away from fossil fuels and reducing CO2 emissions than bankrupting the citizens of America.

Steve

this bill needs to be voted Down. Cap and Trade will be another to Tax all of us to death. OBama and has dem.cronies are on target to ruin the USA, don’t let them get the votes- Wake up World!

Eric

Just as with the new payoff to unions in restricting all large government contracting to (25%) union contractors this bill of gives the the party in power a huge tool to reward campaign contributors. Coupled with the elimination of the corporate contribution limits guess what? Goodbye to democracy as we knew it, hello to new unbridled political power. No suprise the militias are beginning to drill in the hinterlands. What a bunch of sheep the rest of us are!

Patricia Ebaugh

If this bill passes it will be armaggedon for every single property owner in the country. If we are required to get a “license” to sell a home which will require retrofitting—this will have a devastating effect on everyone. For Congress to impose this type of taxation is simply not acceptable.

Mawgy

I think many of the provisions in the bill, especially helping homeowners retrofit their homes to reduce energy use are good. There is no provision in the bill about homeowners having to get a permit to sell their homes. Polifacts and Factcheck couldn’t find anything related to the claim posted. New construction will require “green, energy saving standards”. I am very concerned that so many people refuse to face the facts that we cannot continue as we have. Changes have to be made or our grandchildren will have to wear gas masks to play outside. None of us have to have everything the TV promotes as “in”. We can and will eventually become more efficient and conservative, there really are no more options left.