In an earlier version of this post, the comments thread degenerated into an overheated argument between me and Charles Komanoff, who’s a noted expert in carbon taxes. Mea culpa. I’ve rewritten the post slightly to improve the clarity and, I hope, forestall the antagonism, if not the disagreement…

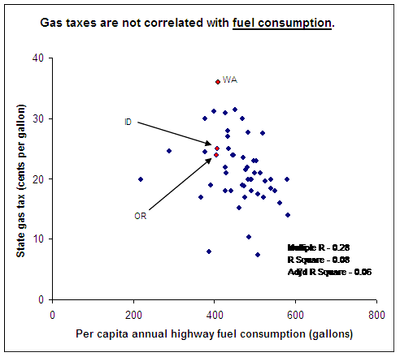

This is surprising: to date, state gas taxes appear to have had very little effect on either driving habits or fuel consumption. Or, more precisely, there’s been no correlation between a state’s gasoline tax and the amount of fuel its residents use or the amount of driving they do.

Don’t believe me? Then feast your eyes on these babies:

And:

Those are big, fat, and completely uncorrelated blobs. What you’re seeing is all 50 states plus DC plotted to show a relationship between state gas tax rates and per capita fuel consumption (in the first chart) and per capita miles driven (in the second chart). You can see that there is essentially no relationship whatsoever.

Maybe this shouldn’t be surprising. We know that raising the price of gas reduces its consumption. That’s something we all saw clearly during the 2008 price run-up. But there are at least two very good reasons why state gas taxes don’t appear to reduce consumption. For one, the tax revenues are dedicated to boosting consumption. In fact, in most states, gas taxes are set aside especially for building and maintaining roads.

So state gas taxes are sort of like tobacco taxes… if the tobacco revenue were funneled into advertising cigarettes. The tax slightly reduces consumption, but the use of revenue slightly increases consumption.

And for another thing, state gas taxes are pretty small.

They’re small enough, anyway, that they are scarcely visible in the price at the pump. Even though there’s a pretty large difference between state tax rates—from 7.5 cents per gallon in Georgia to 36 cents per gallon in Washington — they only account for a small fraction of the consumer price. For a typical state, with a tax rate in the neighborhood of 21 cents per gallon, state gas taxes would account for only about 10 percent of the purchase price—and maybe as little as 5 or 6 percent during the summer of 2008. So although price matters, state taxes aren’t high enough to make a noticeable difference.

In addition to the two factors I mentioned above — the use of revenue and the small size of the tax rates—there may be dozens of other factors that work to obscure the relationship between tax rates and behavior, such as the relative wealth of states, disparate levels of urbanization, differences in physical geography, and so on.

There are a couple of lessons, I guess. First, a general one: if you want to use taxes to reduce consumption, you probably shouldn’t spend the revenue to promote consumption. (This isn’t a knock against state gas taxes; they weren’t designed to depress gas use, but to fund infrastructure.) So that means that a carbon tax would still work to reduce carbon emissions as long as the proceeds aren’t used to promote carbon emissions.

The second lesson has a Northwest policy application and it’s a two-parter. States like Oregon that are considering switching from a fuel tax to a mileage tax should consider the following. Number one, the existing state gas tax doesn’t appear to be doing much to reduce fuel consumption. And number two, taxing mileage at a relatively low level may not do much to reduce driving. That’s in part because Oregon’s proposed mileage tax would be much like existing state gas taxes: it would be designed to support more driving.

But what does this mean for policymakers? And how can we change the way state gas taxes work? Check back here soon to read Benita Beamon‘s upcoming post to find out. Benita is an expert in road pricing. She’s also an associate professor of industrial engineering at the University of Washington and, we’re proud to say, the newest Sightline Fellow. She’s going to bring her brainpower to bear on this subject and some others.

Notes: Fuel consumption and driving figures come from the US Federal Highway Administration’s most recent data here and here. Per capita rates are calculated using 2007 population data from the US Census Bureau, here.

The Two Jakes

Charles Komanoff is mostly a noted expert on shouting at people who question his rigid orthodoxy on carbon taxes. No mea culpa required.

Amy

Until the great day arrives where we see $1+ gas taxes, I think those who love the planet should start the gas equivalent of a swear jar, and donate a set amount for each gallon of gas they purchase. The money could be used to buy carbon offsets or fund green projects at OurJoules.

E Kretzmer

From what I can tell, these graphs just show that people in different states have very different driving patterns that don’t seem to correlate with their states’ gasoline taxes. A real test of the effect of price on consumption and driving would be to examine changes when prices change. I sure noticed that traffic lightened, transit use jumped and SUV sales slumped last summer when gasoline hit $4.

Barry

Yes, the total price per gallon is the only figure that matters.And we saw that somewhere between $3 and $4 that it had huge effect on consumption, and on mpg-factor in car purchases.Whatever we do, cap or tax or both, it will have to send the signal that gas will stay above $3 forever. And that gas price will increase for certain over time.This can be done simply and quickly with a gas “floor” tax. It could be in place within months statewide or nationwide. And it would have it’s own “magic” self-adjustment. It would totally disappear when market forces drove gas prices higher. Zero carbon price resentment when price gets painful on it’s own. And it would not allow gas to fall to very low levels like now…which would prevent the millions of disastrous vehicle choices that are now being made. That too is “magic”. We can’t get the needed level of gas sanity however with a flat gas tax as Eric points out.

James Handley

Liked Eric’s earlier post showing that improving fuel efficiency from 15 to 18 mpg saves more fuel and CO2 than upgrading from 50 to 100 mpg would. Terrific conclusion: banning the most inefficient vehicles would be more effective than cafe (average) standards. But on this non-correlation, I think he’s goofed. A correlation between state fuel taxes and driving habits, wouldn’t tell us which is the cause and which the effect. Fuel taxes might just be unpopular in big, rural states. I don’t think there’s any doubt that fuel prices change driving and vehicle purchasing behavior. See, e.g., “Driving Less, Americans Finally React to Sting of Gas Prices” NY Times, June, 19, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/19/business/19gas.html.If fuel prices were expected to continue rising (e.g., a gradually-increasing carbon tax) we’d see much more conservation and efficiency upgrading. Volatile prices make investments in efficiency a gamble.

Eric de Place

Good points, James.It’s always wise to remember that a correlation—or the absence of a correlation—doesn’t tell us much about cause and effect. That said, consider the obverse(?) of your hypothesis that gas taxes are unpopular in big rural states: gas taxes are popular in small urban states. If you hypothesis is right, then it would seem surprising that we don’t see some kind of correlation between tax rates and behavior. But as I said in the post, maybe it shouldn’t be suprising. Price is what matters—and state gas taxes are only a very small share of the total price. (It also doesn’t help that the revenue is plowed into encouraging driving.) Suffice it to say that I completely agree that price affects behavior. I’ve spilled quite a bit of cyber-ink making that very point on this blog! As readers know, I’m sort of obsessed with carbon pricing.What the absence of correlation suggested to me was that maybe state gas taxes are not the best policy mechanism for increasing the price in order to reduce driving. I thought that was interesting enough to jot down and share.

James Handley

Eric, True, small or unpredictable taxes may not change behavior if the price signal gets lost in noise. The widely observed short-term reductions in driving in response to last year’s price increases suggest to me that a gradually-increasing fuel tax (state or federal) could have even more benefits by changing long-term price expectations.

Barry

I just want to point out again that it is the price of gas…not the level of tax…that must clearly be known to be always rising.The market price of gas is highly volatile. It has been in the past. According to economic theory it will be even more so as we hit supply vs. demand limits. Market volatility is likely to be high.If we want to reduce fuel consumption significantly long-term, consumers at all levels must believe that gas prices will stay high and rise.In other words we must have policy that sets the actual gas *price* not just some *tax* level. Long-lasting fossil-fueled infrastructure decisions will make us or break us on this. We must have *price* controls to ensure these are made sustainably at all times.As BC’s flat carbon tax and cap & trade carbon pricing have shown, the carbon price becomes useless in preventing many bad infrastructure decisions when prices fall significantly.

Charlie

More than 20 years ago, the Economist described the effects of a “floor price” for gasoline, also of a ratcheting tax: reducing congestion, pollution, big wasteful cars, etc. It wouldn’t reduce “choice” (sacred cow of the big 3 and others), but would make the choice to waste gas a more painful one. I’m an enthusiastic proponent of both these tools, largely because of the opportunity they present: a $4 floor-price tax would generate huge revenues at a time when we will need revenue to pay national debts, and it’s like a user fee: the wars fueled by petro-cravings could be paid for efficiently by those who benefit from the spoils. If we really need to take over the world’s remaining petroleum capacity for our big cars, let’s set the floor price at $5 or $6/gallon, and let the users fund the wars. Oops: Did I that out loud?