My backyard garden is giving me mixed results this year. I did okay with the strawberries and snap peas, but the peppers are only so-so and the tomatoes are downright pathetic. Personally, I’m chalking it up to the lousy spring, not my laissez-faire attitude toward vegetables.

Still, I love it. My garden is definitely not saving the world or anything, but there’s something weirdly profound about coaxing food from the ground. (Or in my case, coaxing some dicey-looking salad greens from the planter box.) Growing food scratches some peculiar itch we have, whether it’s a glimmer of our agrarian past or a sense of self-reliance. It may even be good for us.

While eating locally is probably not the most important environmental decision we make at mealtime it often has important benefits. (More on these below the jump.) But what’s local? And can we city dwellers really sustain ourselves locally?

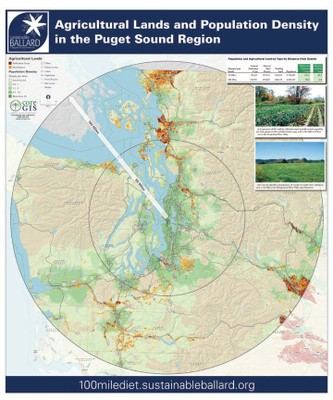

Enter Matt Stevenson — Sightline’s friend, periodic GIS contractor; he’s a data-fiend and map-maker. So I wasn’t surprised to see that he’d produced this map showing where you can eat on 100 mile diet if you live in Seattle:

This 100-mile diet would be tough. There’s some good farmland—especially in the Skagit and northern Willamette Valleys—as well as some opportunity for seafood. But there’s a lot of dense forest in there; a lot of rock and ice; and a lot of development too.

Sure, fine. But Matt isn’t satisfied with general qualitative remarks like these. He crunched the numbers to figure out how much farmland we’re protecting near our urban areas—and whether it could sustain us. The news isn’t great.

In his blog post that accompanies the map, Matt writes:

As it turns out there is far less acreage in cultivated crops than in hay/pasture, and within 50 miles, each acre of cultivated crops would need to feed 172 people! If we assume that all of the hay/pasture can be converted into cultivated crops, the number of people supported by one acre drops to 22. Moving out to 100 miles improves the situation, with just under 31 people per acre of cultivated crops and just under 7 per acre for all agricultural land.

That means the numbers doen’t pencil out under any set of assumptions:

However, according to one study, a meat-based diet requires 9 acres per person! A diet that is primarily plant-based (with some milk, cheese, and eggs) requires 3/4 of an acre.

So even if we all became vegetarians we couldn’t sustain ourselves on the amount of farmland nearby (to say nothing of the type of farmland and local growing conditions). Not even close, although I’d be curious to know how the number change if we extended the line another 50 miles or so to capture the fertile valleys on the east slopes of the Cascades.

Here at Sightline, we’ve written quite a bit about local food and its benefits (see here for a list). But the general tenor is that it’s very difficult—make that very, very difficult—to quantify the climate attributes of food, whether it’s local or long distance. One recent study, reported in an engaging article called Do Food Miles Matter?:

…found that transportation creates only 11%… of the greenhouse gases… that an average U.S. household generates annually as a result of food consumption.

I guess there are several ways to parse this. I think 11% is kind of a lot. But on the other hand, a big chunk of that transportation figure is from consumers getting to and from the store (or farmers’ market); it has nothing to do with the locality of the food source.

Still, all else being equal, local food may shave some greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel consumption. Plus, not everything is about climate emissions. Eating local can have positive economic and cultural benefits: it helps sustain local farms and can encourage niche industries like troll-caught fish, organic poultry, or heirloom vegetable varieties. And at the end of the day, eating local is a bit like gardening: it’s just really, really satisfying somehow, even if you can’t put your finger on why.

Ron

There have been some interesting studies done on the situation in post Soviet era Cuba being forced to go low carbon across the board. They’ve become very creative in creating urban gardens in empty lots, yards, and containers to sustain themselves. My guess is that we are going to be forced to take their lead in the coming years as carbon based fuels become more scarce and expensive.

Amy

I wonder how much the numbers improve if you take backyard (or front yard for that matter) gardening into account. If most people with the yard to do so planted a garden and then put-up the harvest how much of their food could they produce?

Shira

Many cities around the world produce 35-50% of what they consume in or close to city, including Moscow, Havana and Hong Kong. Fruits and vegetables are mostly water and well suited to intensive cultivation. I don’t believe that growing the nation’s vegetables in California with industrial agriculture and sending them to Seattle by truck is truly more energy efficient, and even if it is, I don’t care. I can walk outdoors in my fuzzy bathrobe and get fresh organic vegetables from what used to be my front lawn most of the year. Not only is it cheaper, fresher and more interesting than buying limp broccoli that spent three days in a truck, there are far fewer parts of the system to break. My inputs are city water, seeds and some local horse poop, compared to a whole industrial agriculture system. The heavy carbohydrates are field crops, but we even have some of those not too far away. The Palouse produces pulses and soft white wheat. Idaho is part of the nation’s breadbasket. I never have believed in the purist 100 mile diet anyway. Coffee, tea, cocoa and spices are compact, valuable and relatively light,and have been international trade commodities since long before the industrial age. Good for Matt, to crunch the numbers. The next level of analysis requires a close look at each neighborhood, looking for roundabouts, planting strips and vacant lots that can be planted in vegetables and places for fruit or nut trees. Small meat animals are raised in cities all over the world. Flat roofs are great for pigeon coops. The janitor had a squab raising operation on top of the high school when I was a kid.

Sheila

Amy, your idea sounds great, but our economy generates value in large part by specialization. Not everyone is good at gardening or canning, as Eric’s post illustrates. Specialization is what lets me do what I do well and lets someone else make my clothes, which I frankly stink at. So, suppose we could let people who are good at farming take advantage of these front and backyard gardens? After all, there are entrepreneur gardeners here in Portland (and I suppose in Seattle too) who for a (big) fee, will plant and care for your garden and deliver the produce to you. But thousands of small parcels would be incredibly inefficient. If you think farmers’ market produce is expensive, think about how much more labor would be required if a farmer had to work over many small plots in front and back yards? Furthermore, there is a trade-off between using open space for gardening and using the space to add density (or add parks to make density more acceptable) so that we can keep our UGBs tight and preserve more farmland outside the urban areas.So…this is a complex problem that requires a variety of solutions.

Dave

Actually, Eric, your comment that “a big chunk of that transportation figure is from consumers getting to and from the store (or farmers’ market)” is not accurate.The study states, “It should be noted that this figure [11%] does not include consumer transport to and from retail stores, which is both outside the scope of this study and complicated by multipurpose trips.” VOL. 42, NO. 10, 2008 / ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY / p. 3509http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/sample.cgi/esthag/2008/42/i10/pdf/es702969f.pdfWhat’s interesting is that the “final delivery from producer to retailcontributes only 4%” of total food greenhouse gas emissions. This is the “food miles” part of the equation that locavores key in on.Having an affinity for local food myself, I find it hard to argue with good scientific data that challenges the easy “intuitive” preconceptions that many of us have about “food miles”.

Eric de Place

Nice catch, Dave—thanks.I was making assumptions based on other figures I’d seen like this one. It’s a cautionary tale about making assumptions, I guess…