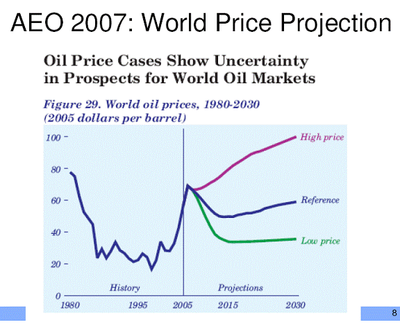

Predicting the future is hard. It’s so difficult that even teams of analysts using fancy models get results like this:

This isn’t back-of-the-envelope stuff. This is the US Energy Information Administration’s official prediction for oil prices, circa 2007. According to the “high price” scenario, oil may reach $100 per barrel some time around 2030. But wait: oil was at $127 yesterday. So, not only was the EIA projection wrong—it was wildly and completely wrong.

Okay, everyone makes mistakes, even energy analysts. In 2008, the EIA cleaned up its act and produced this forecast:

As you can see, in the “high price” scenario, oil will almost reach $120 per barrel around 2030. At the risk of repeating myself, oil was at $127 yesterday! So, the EIA projection is still wildly and completely wrong.

Ordinarily, this would be jolly good fun. But it’s not so funny when these kind of projections are used to make decisions with big consequences. These two charts, in fact, come from the Western Climate Initiative’s economic analysis, which is being conducted by consultants. (The forecasts shown in the charts are the data inputs for a model that is supposed to inform policymakers and thereby guide the design of the cap and trade program.) But the data inputs are laughably wrong.

Of course the consultants are well aware of the problem. And they’re already trying to develop new forecasts to use in their modeling exercise. Plus, in their defense, the reason they planned to use EIA data was that it’s probably the best available and it’s considered highly credible.

In any event, the WCI consultants will probably use new and improved EIA data to update their models. That would be fine, maybe, but the EIA seems to have a hilariously persistent tic. Check out this chart via Kevin Drum:

The black line is actual prices and the colored lines are monthly forecast revisions. The black line (the price) keeps going up, and every month the EIA forecasts a decline, starting immediately. It’s as if the forecasts are impervious to reality.

On the other hand, who knows? The EIA could eventually turn out to be right and the current high prices may evaporate. But even if that happens, it’s a bit worrisome that our climate policy might be based on forecasts that are so wildly and consistently inaccurate. And this stuff matters. A lot.

All else being equal, forecasts of lower oil prices will tend to raise the predicted costs of climate policy. In part, this is because cheap oil means lots of consumption and intractable behavior. But if oil prices are high in the future, as they are now, then a cap and trade program might add only small costs—or even result in savings. So the EIA’s perpetual sunshine-optimism about future oil prices might create a big distortion of the cost of sensible carbon reductions.

All this to say that it’s tough for even the best minds to predict the future. Not that we shouldn’t do our best to calculate costs and minimize impacts—we definitely should! But our projections for the future should be leavened with a heaping spoonful of skepticism.

Matt the Engineer

Then again, not everyone has this much trouble with graphs. For instance, searching with Google Images for (peak oil price), the first relevant graph is this, which did a much better job in 2007 predicting current prices – even though the price of oil was dropping at that time (they predicted we’d be at around $118 around now – source here).Could it be that they’re just using the wrong model?

Matt the Engineer

And the next relevant graph is from New Zealand’s government, who apparently knew something like this was coming since 2005 (ok, so they predicted we’d be closer to $108 right now).

Matt the Engineer

(there’s a link that goes with that)

Eric de Place

Great charts, Matt! Thanks for sharing those.Using the wrong model could be part of the problem. But the meta-difficulty here is that it’s very tough to adjudicate between the projections of competing models and analytical tools. (At least until one has the luxury of hindsight, in which case it’s easy.)

Matt the Engineer

Of course you’re right in general, but it seems to me that the specific case of oil models the issue is at a higher level: deciding whether or not we’ve hit peak oil. It seems clear from the charts above that the EIA doesn’t think we’re there yet, and it seems equally clear from peak oil charts that we’ve passed it.

barry

I’m with Matt on this one. The EIA is notorious for “endless oil” enthusiasm. I’m not sure who sees them as “credible” in recent years.If you “follow the money” it become clear why there is so much cheerleading for a bountiful oil future and low prices returning soon. There are billions to be made by keeping people believing in this as long as possible.The people who gain most right now from high oil prices and restricted supply, aka peak oil, are the oil companies. Check the profits recently. Who wouldn’t want to be able to raise the price of their product 500% in five years? With no serious competition on the horizon and multi-decade infrastructure turnover rate…it’s money-printing time. Conversely, the people who lose the most from peak oil reality sinking in are once again the oil companies. The longer we wait to seriously develop alternative energy sources…the more oil hogging infrastructure we buy in the hope of yesteryear returning…the longer we are hooked on oil at any price. A serious “Marshall Plan” approach to a post-petroleum world is in direct conflict with the largest cash cow in history. Enter the wacky charts and rose coloured glasses.

Matt the Engineer

I recently came across the wikipedia article on peak oil. The EIA and OPEC seem to be the only two groups that don’t predict peak oil (at all, apparently ever). OPEC’s model predicted in 2007 that “oil resource base is sufficient to satisfy demand increases until 2030 at a price of $50-60 per barrel, increasing afterwards to account for inflation.” Oops. What’s a barrel of oil at now, $132?

Todd Eastman

Hmmm… If only one could sue economists for malpractice!Todd Eastman

ben

seems like they were pretty much spot on to me…