A recent study (pdf) by my old friends from the forestry department at OSU finds that when you add up the gains and losses, ecosystems in Oregon stored about 8 million tons of carbon per year between 1996 and 2000. The forests west of the Cascades, in particular, were prodigious carbon sinks. (A carbon sink is basically something that removes more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases; it’s mostly being stored in trees and soil in this case).

In case you’re wondering, 8 million tons is a lot of carbon storage. In fact, it’s enough to offset about half of the state’s total fossil fuel emissions.

Which raises a huge question: given the huge amounts of carbon that Northwest forests can capture and store, what role should they have in climate policy?

I still haven’t decided how I feel about this issue. Forests have gained a lot of attention in the climate change debate because of their ability to suck carbon out of the atmosphere. You can support reforestation projects by buying offsets on the internet. Land managers want to sell credits for carbon stored in trees and wood products as part of a cap-and-trade system. Some cities are even planting trees as part of their efforts to slow climate change. Forests store so much carbon that policymakers ought to pay attention to them. But as this study shows, integrating forest protection or reforestation into, say, a cap and trade system carries huge risks.

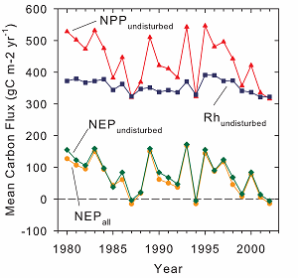

To explain what I mean, let’s start by looking at one of the figures from this study (Bear with me, I promise you will be smarter at the end of this paragraph.) The top line represents yearly “Net Primary Production” or NPP, over 20 years. NPP is basically the amount of carbon trees take out of the atmosphere through tree growth. The middle line represents “Respiration” (Rh), or the carbon losses from decomposition of dead needles and wood. The bottom line represents Net Ecosystem Production, or NEP. Stated simply, NEP = NPP minus Rh. Carbon storage equals uptake minus releases.

So when NEP is positive the state’s ecosystems are a carbon sink (taking carbon out of atmosphere) and when it’s negative they’re a carbon source (releasing carbon to the atmosphere). And as this graph shows, the losses are fairly constant while the gains change a lot from year-to-year. How much forests grow each year determines whether the state is a source or sink.

As someone who’s worried about over-reliance on forests as a major tool of climate policy, these three things concern me most:

- Oregon was a big carbon sink some years and a source in others. For example, the state was a net source of carbon in 2002 for two reasons: the notorious Biscuit Fire (which caused huge carbon losses all by itself) and dry weather (which slowed tree growth).

- The size of the carbon sink is closely correlated with precipitation, especially in the spring and summer. When it’s really dry, trees don’t grow as much (Makes sense, right?) But most regional models of climate change predict that Oregon’s summers will get warmer and drier. That suggests that Oregon‘s forests may be a smaller carbon sink in the future, or even perhaps a source of carbon emissions. Moreover, drier weather conditions can also lead to more fires, which further reduce carbon stores.

- According to this study and others, the best way to store carbon in forests is to avoid logging them (or at least cut them less frequently), because wood products store only a portion of the carbon stored in standing forests. Great, so we should stop logging or increase rotation times in the U.S and Canada, right? But there’s a problem here too: unless we make meaningful changes in our consumption of products, preserving our homegrown forest will probably come at the expense of forests in the developing world.

If forest carbon offsets are going to have an important role in climate policy, the storage they provide will need to be permanent, predictable, and real. But if you buy the argument above, none of that is guaranteed. In a warmer world, even old-growth forests aren’t necessarily permanent; year-to-year variations in growth, as well as forest fires, make forest carbon sinks unpredictable; and storage may not even be real, if protecting our forests means that others are cut in their place.

Don’t get me wrong: I think managing forests for increased carbon stores has a place in our climate policy puzzle. I just find little reason to think that Northwest’s forests should be a central part of that equation.

CitizenJ

What I like about this article is the integration of the question and supporting information. Framed as our current understanding allows, we do have a serious problem re-sequestering millions of years of carbon storage that has been released by expanding human populations and energy use over the short span of 150 years.The forests have a role, many roles actually, and a first step could be improving basic management versus the political and funding neglect of the past 30 years or so.As the article and study point out, there is a valid question if the forest can be viewed as “storage” (an end point objective). There seems little argument about the forest’s viable and effective “collection” of carbon from the atmosphere (a front end process need).What happens between these end points is reason for excitement about this region we call home: forests will only become more and more important in everyone’s lives.And, we just happen to have a few significant forests around here!

Dan

The issues wrt policy are: what is a ton? How long is it the same ton? How do you re-offset when logging ops occur or distrubance occurs?

Bob Zybach

This is a thoughtful, well considered posting. I presented a paper on this topic at an international workshop of scientists cosponsored by EPA and Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon in 1991. Following peer-review, the paper was published in 1993.A few months ago I was asked to address this topic as the focus of a one-hour interview by a local radio station. Both the paper and the interview can be found here:http://www.NWMapsCo.com/ZybachB/Reports/1993_EPA_Global_Warming/index.htmlTwo points in the post can use further discussion: 1) Not only does the current series of catastrophic-scale PNW wildfires produce enormous amounts of CO2, but all of the rotting snags left behind continue to pour CO2 into the air, until they are reburned in a subsequent wildfire event or harvested to make biofuel or stable wood products; and2) If CO2 is actually the environmental travesty that the Gore camp is promoting, then forest management can be taken a step further, and harvested logs can be sunk or frozen in log rafts (“carbon banks”) and preserved for the use of future generations when CO2 counts are more acceptable.Finally, recent news that an underwater logging operation was good for the environment because it reduced clearcutting living forests is just wrong, from a CO2 standpoint. Forests flooded during reservoir filling events hold their carbon in almost perpetuity because submerged wood can’t rot. It is only when the logs are brought to the surface and developed into other products that they begin emitting CO2 into the air. If the GW enthusiasts are correct, those trees should be left underwater for a few more centuries, at least.

cheney

What about commercial thinning the stands so it takes them longer to reach comulation age. Studies have shown that does not reduce wood production in Douglas fir stands well lengthening the rotation

Bob Zybach

Cheney:I think that harvesting snags and other deadwood, and “commercially thinning” existing stands are the two best strategies for Oregon to use its forests to reduce CO2 emissions (while conserving resources, improving wildlife habitat and aesthetics, and greatly reducing risk and severity of future wildfires). The first commercial thinning I would do would be to remove ladder fuels, competing vegetation, and basal fuels at least a full tree-length from all remaining old-growth (200+ year old trees and shrubs) that have survived the wildfires of the past 20 years, and the preceding 40 years of clearcuts.

Doug Heiken

Nice, post! You are right the the solution is to apply “long harvest rotations” in managed forests. We must also stop logging forests that currently attain close to their potential of carbon, such as old growth forests. Even if our great NW forests do become carbon sources in the future, we can certainly make a bad situation worse if we log them irresponsibly. I have done some digging into this topic and wrote a report, available here.

Anonymous

I appreciate the thoughtful responses. I agree with Doug and Bob (and pretty much everyone else) that well-managed commercial thinning is probably the best way to promote carbon storage in managed Northwest forest landscapes.Promoting carbon storage is important in our forests, we just need to be careful that our policy is built on scientific principles and doesn’t provide perverse incentives to private land managers.

kcharm

I seem to recall reading an article or hearing a news report recently on how little protecting forests outside of the tropics will do to resolve global warming. The theory had something to do with light absorption and its associated heating rather then the reflection off of buildings. Something tells me that these statements I had heard (or read) are a bit of stretch, but the best lies have a thread of truth in them. Could somebody comment on this?

Anonymous

There has been some talk about the warming effects of trees outside the tropics over at grist. They refer to a study out of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. They find that high latitude forests probably have a ‘net-warming effect’ on the climate. This is just one study at the global scale, so I wouldn’t put too much faith in it. However, it complicates the debate some more and adds another major question mark to using forest offsets to mitigate climate change.

Doug Heiken

In response to KCharm, the study you are referring to is about “albedo” which refers to the reflectivity of different land surfaces. Snow and deserts are relatively reflective and tend to cool the local area, while oceans and forests are relatively dark tend to absorb energy and warm the local area. Recent studies reveal that in boreal forest zones the warming caused by carbon emitted when boreal forests decline (due to logging or fire for instance) is more than off-set by the cooling caused when snow falls and stays on the ground for long periods to reflect heat back to space. In areas where forest loss is not typically followed by seasons-long snow accumulation, the same off-setting albedo phenomena is not present. Here in the northwest, snow does not stay long during the winter at most elevations, and “dark” absorptive vegetation regrows rapidly after fires and logging, so it makes sense to store as much carbon as possible here in the mild temperate areas. This is covered in my report:http://tinyurl.com/2epzrk