Could 2018 be the year that Oregon and Washington join BC and California and make climate polluters pay? Jay Inslee, the governor of Washington, is pushing a carbon tax (more on that soon), and Oregon legislators are again considering legislation to limit carbon pollution and invest in clean energy and other good things. In 2017, a bill to cap pollution, enforce the cap with limited allowances, and invest the revenue in Oregon attracted 33 co-sponsors. Work groups continued hammering out the details in the fall. The 2018 bill reflects years of refining, has Governor Kate Brown’s support, and is ready for the legislature to pass.

Urgent need for action

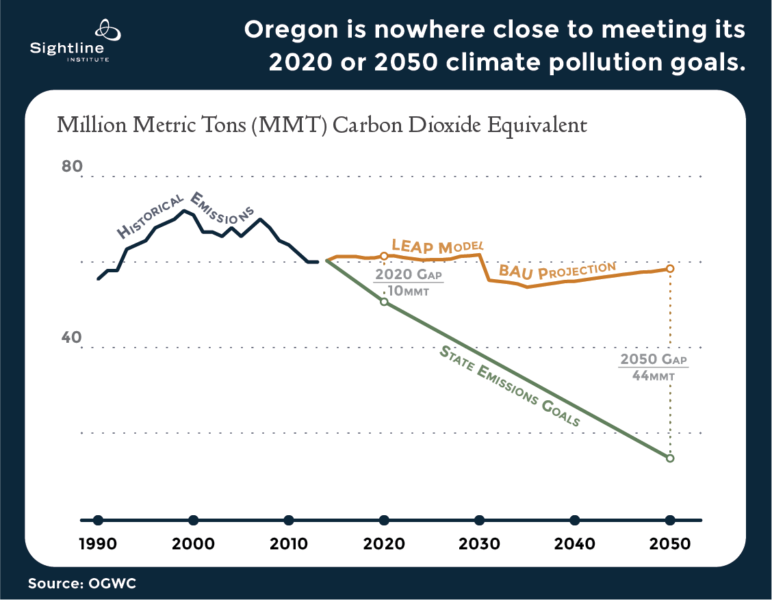

Climate change is already threatening Oregon with declining snowpack, wildfires (which are only getting worse), flooding, and ocean acidification. Oregonians see these changes and want to take action. In fact, Oregon law says the state should reduce pollution 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2020 and 75 percent below by 2050. But the state is not on track to meet its climate goals. Frankly, Oregon can’t even see the track from where it stands. The chart below shows the yawning chasm between where Oregon wants to head (the green line) and where it is actually headed (the orange line).

Oregon’s other climate efforts, such as investments in energy efficiency, the Clean Fuels Program, and Renewable Portfolio Standard are keeping Oregon’s emission flat despite a growing population. (The dip in projected emissions around 2031 in the graph above is due to utilities getting rid of the coal power they currently depend on to serve Oregon customers. In 2016, the Oregon legislature ordered utilities to be coal-free by 2035.) But flat isn’t good enough. Oregon needs to pollute less to meet its own goals and do its part to stabilize the chaotic climate. To pollute less, Oregon needs something like the Clean Energy Jobs Bill.

Updated goals to slash pollution

The Clean Energy Jobs bill updates Oregon’s existing pollution reduction goals to ensure Oregon does its part to contribute towards the international Paris Climate Accord goals to limit global warming pollution. The bill would commit Oregon to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions:

- 20 percent below 1990 levels by 2025;

- 45 percent lower than 1990 levels by 2035; and

- 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.

A cap on most emissions

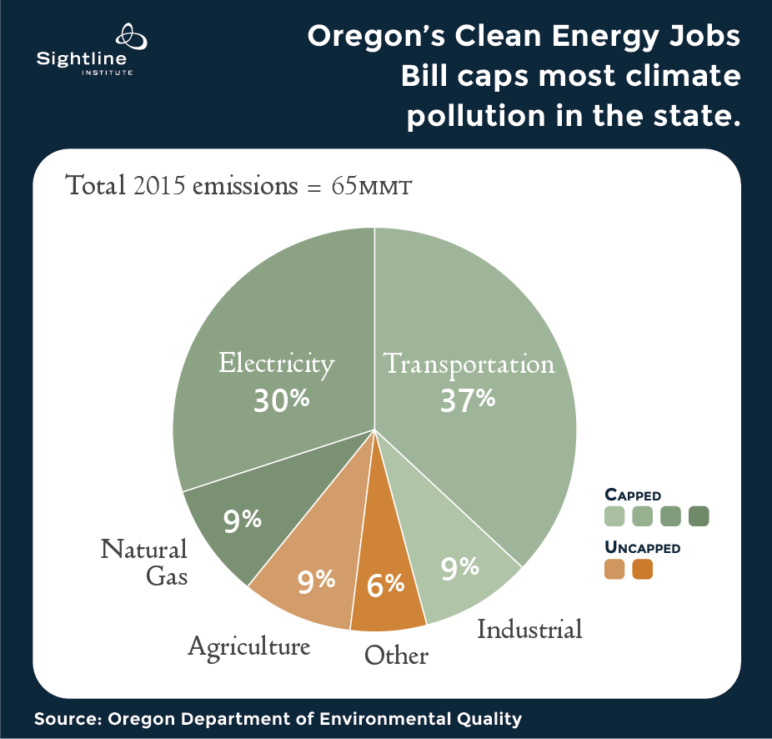

Oregon’s climate pollution comes largely from burning fossil fuels—burning oil for transportation, burning coal to generate electricity used in oregon homes and businesses, burning natural gas to heat homes and power industrial operations. The bill would cap pollution from the state’s biggest coal, oil, and gas polluters—industrial facilities and utilities emitting more than 25,000 tons of pollution per year, as well as importers of transportation fuels. This would help Oregon shift off dirty fuels and onto clean, renewable energy. About 85 percent of all of Oregon’s climate emissions would come under the cap, forcing emissions down year after year.

The cap does not cover agriculture and forestry emissions nor marine and aviation fuels.

Investments in Oregon

Limiting pollution is the bill’s first key action, and the second is investing revenue to benefit Oregonians and boost Oregon’s clean-energy economy. To enforce the cap on pollution, Oregon would use a limited number of allowances—large entities would have to turn over an allowance for every ton of pollution they emit, or face harsh penalties. The state would auction the allowances, generating revenue to be invested.

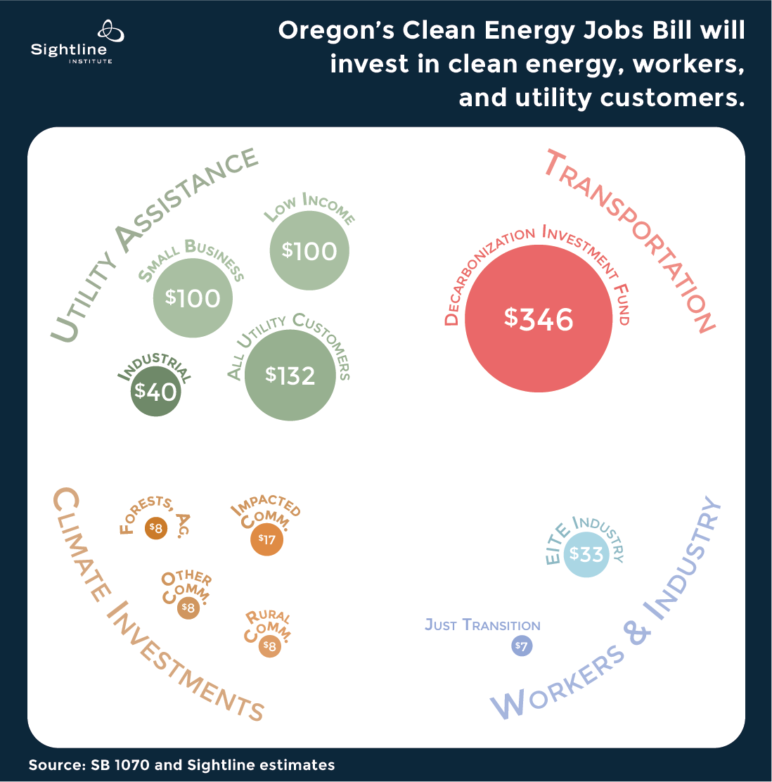

Oregon’s constitution hoovers up all the revenue from the transportation sector—about 43 percent of the revenue because transportation is Oregon’s biggest source of pollution—into the Highway Trust Fund to be spent on “the construction, reconstruction, improvement, repair, maintenance, operation and use of public highways, roads, streets and roadside rest areas.” Assuming an initial auction price of $15 per ton, that’s close to an annual infusion of $350 million earmarked for highways and roads, inflating the existing $550 million Highway Fund by about 60 percent. If the state spends that money expanding highways, as the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) often likes to do, it will shoot its clean energy transition in the foot before making it out of the starting blocks.

Cleverly, the bill sequesters the money into the “Transportation Decarbonization Investment Fund,” a sub-account within the Highway Trust, dedicated to projects that combat climate change, such as local street maintenance, which improves transportation efficiency and which cities and counties desperately need. To ensure the money gets to localities, the bill would need to clarify that the Transportation Decarbonization Investment Fund could go to local jurisdictions, instead of following the existing revenue distribution split, which gives the lion’s share of Highway Fund revenue to ODOT. The bill does allocate 60 percent of the fund to “purposes that benefit impacted communities,” but maybe ODOT will argue that new highways help people and the climate.

The second biggest chunk of revenue, 35 percent of it, will go to electricity and natural gas utilities to use on behalf of their customers to cut pollution and reduce energy bills. In order of priority, utilities would be required to spend this money on:

- assistance to low income residential customers, including renters

- public entities, non-profits, or small business

- industrial customers that must use a lot of energy to run their business but are not already receiving allowances (see below)

- all other utility customers

The bill is clear about the order of priority, but doesn’t bind the utilities to specific numbers, so the chart below shows rough guesses about how the money might break down within those categories.

Energy intensive, trade exposed (EITE) industries—those, like cement and pulp and paper manufacturers, that must use a lot of energy to create their product and that also face competition from outside Oregon—will get up to 90 percent of their allowances for free to ensure they don’t take business and jobs out of the state because of increased costs from the climate program. It remains to be seen how many Oregon industrial businesses actually meet the definition of EITE—the bill directs the Environmental Quality Commission to hire a third party organization to help identify them. For the moment a conservative estimate is that 40 percent of industrial sector emissions come from EITE industries. The revenue from the remaining industrial sector businesses is dedicated to two funds:

- 85 percent would go to the Climate Investments Fund to invest in projects in Oregon that help people and reduce pollution.

- Within this Climate Investments Fund, 40 percent would benefit communities most impacted by climate change. The specific communities are yet to be designated, but will be places that have high concentrations of low income households, high unemployment, low levels of homeownership, high rent burden, low education, and are disproportionately affected by environmental pollution, with more weight given to factors that predict vulnerability to the impacts of climate change and ocean acidification.

- 20 percent would benefit rural communities impacted by climate change.

- 20 percent would be invested in carbon sequestration in natural and working lands, including forestry, agriculture, rangelands, and coastal areas.

- 20 percent could be used anywhere in Oregon for projects that either (i) reduce greenhouse gas emissions and make communities more resilient to the effects of climate change or (ii) increase carbon sequestration and heightened resiliency in natural and working lands.

- 15 percent would go to the Just Transitions Fund to help workers transition to the clean energy economy.

- Up to $2.5 million would be reserved for direct financial support for dislocated workers.

- The remainder of the Just Transitions Fund would go to training and retraining in clean energy jobs.

More design details

To keep prices steady, the program includes a price containment reserve and the ability to bank allowances. It also allows for offsets—pollution reductions that occur in the forestry and agricultural sectors where emissions are not capped. Offsets can infuse money into replanting and preserving forests by allowing capped polluters to save money by paying for reductions elsewhere instead of paying for allowances. Offsets are controversial because of the potential to allow large polluters to continue polluting for longer than they would have if the offsets were not available, so legislators have not quite landed on exactly how many offsets to allow. The House version allows polluters to meet 4 percent of their compliance obligations (their total pollution each year) from offsets, while the Senate version allows up to 8 percent, but specifies that half of those must produce benefits in Oregon.

Although previous versions of the Oregon bill would have set up a program capable of linking to other North American jurisdictions that are already making polluters pay (California, Quebec, Ontario, all part of the Western Climate Initiative), this bill is more explicit about Oregon’s intention to link.

The legislation doesn’t spell out every detail of implementation, leaving some of it up to the Environmental Quality Commission, in consultation with other agencies and experts. A 21-member Program Advisory Committee representing diverse interest groups in the state including businesses, rural communities, and Tribes, would advise the Department of Environmental Quality and the Joint Legislative Committee on program design and implementation.

Put it all together

With mega wildfires raging through Pacific Northwest forests and a deafening lack of climate action at the federal level, Oregon’s Clean Energy Jobs Bill is taking center stage at just the right time. It reflects years of work, negotiations, and refinements from a host of people across the state, resulting in a final package that is wrapped up with a bow and ready for legislators to act on. If Washington also acts on Governor Inslee’s proposed bill, the West Coast could at last achieve the dream of a united front for climate action extending from the United States border with Mexico to the northern tip of Canada.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get our latest research here.” selected_lists='{“Sightline Research Updates”:”Sightline Research Updates”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.