“Repeal and replace” may be coming to a stream or wetland near you. A Trump Administration initiative to overturn Obama-era protections for some small waterways could threaten environmental health, and maybe drinking water sources, for over 100 million US residents, including at least 4 million in the Northwest. Following a presidential Executive Order, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has proposed to reverse the 2015 Clean Water Rule, which provides valuable protections for “national treasures” such as Puget Sound.

How did this situation come about? The story starts with the Clean Water Act, one of the nation’s primary environmental protection laws, which establishes federal jurisdiction over “navigable waters,” and “waters of the United States, including territorial seas.” Yet science indicates that protections limited to “navigable” waters could be severely undercut by pollution in smaller tributaries and wetlands that feed into the main waterway. Indeed, as early as 1985, in United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) held that wetlands that intermingle with navigable waters are themselves “waters of the United States,” and therefore fall under Clean Water Act jurisdiction.

In 2006, however, the Roberts Supreme Court complicated the issue of federal jurisdiction in Rapanos v. United States by issuing a 4-1-4 decision, which because it was a tie set no binding case law. The issue in question was the extent of the US Army Corps of Engineers jurisdiction over wetlands when the agency issues permits for the discharge of dredge or fill material into “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act. The lone opinion by Justice Kennedy concurred with one of the plurality decisions that the Corps had exceeded its authority by regulating a relatively remote wetland. But Kennedy also concluded that a wetland or non-navigable waterway would fall within Clean Water Act jurisdiction if there were a “significant nexus,” to a traditional navigable waterbody, affecting the integrity of the downstream water. Justice Stevens, author of the other plurality opinion, supported the Corps’ interpretation in the case, and further assumed that Justice Kennedy’s “approach will be controlling in most cases.”

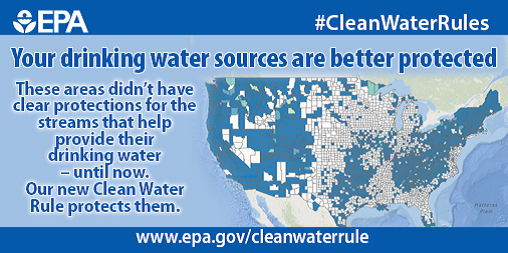

After Rapanos, EPA and the Army Corps attempted for several years to interpret what constitutes a “significant nexus.” After some unsuccessful efforts by previous presidential administrations and Congress, the Obama administration in 2011proposed its “Clean Water Rule,” designed to clarify exactly which Waters of the United States (WOTUS) are subject to the Clean Water Act.

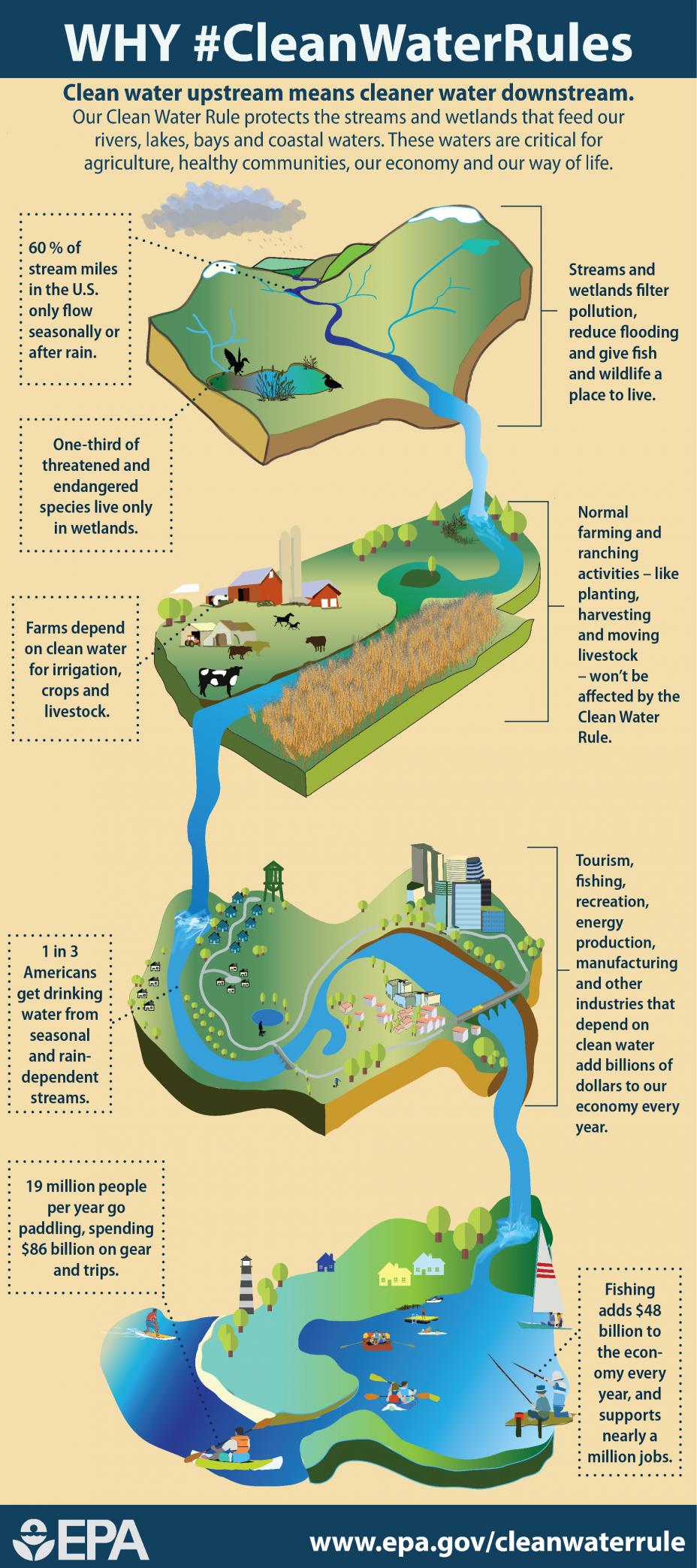

Much analysis supported the new rule. In fact, EPA issued a synthesis of more than 1,200 peer-reviewed scientific publications showing that the small streams and wetlands the rule would protect are vital to larger, downstream navigable waters. The Agency also held more than 400 meetings with stakeholders across the country, and received over one million comments—more than 80 percent of which were in support of the rule. In June 2015, the administration promulgated its final Clean Water Rule, to take effect two months later.

In endorsing the measure, then-President Obama noted, “This rule will provide the clarity and certainty businesses and industry need about which waters are protected by the Clean Water Act, and it will ensure polluters who knowingly threaten our waters can be held accountable… With today’s rule, we take another step towards protecting the waters that belong to all of us.” Then-EPA Administrator, Gina McCarthy, reported that the additional protections would expand the number of water bodies covered by the Clean Water Act by only about 3 percent. Nonetheless, some industries, including agriculture and energy, opposed the rule, thirteen states sued the federal government over it, and federal courts issued decisions blocking its implementation nationwide.

Then, in February 2018, President Trump (POTUS), issued an executive order directing EPA and the Army Corps to review the Clean Water Rule. But Trump’s initiative was plagued with problems from the outset. The Washington Post fact-checked his claim that the Rule has cost “hundreds of thousands” of jobs, and awarded him Four Pinocchio’s (a falsehood Whopper). He also failed to acknowledge his inherent business of interest conflict, since revoking the rule could avoid costs at his golf courses. Moreover, in proposing to revoke the rule, EPA Administrator Pruitt omitted his own legal history: as Oklahoma State Attorney General he had sued EPA over this very same Rule.

What’s next? EPA has invited public comment on its proposal to rescind the Clean Water Rule, with a deadline of September 27, 2017. Citizens can submit comments via an EPA web page, following the directions at the bottom of the “Step One” material.

Earthjustice is already on the case. As the environmental law firm explains, revoking the Rule would remove protections for waters critical to drinking water, recreation, and wildlife. Readers can view the Earthjustice arguments, sign on, and/or add their own personal comments, at this embedded link. The organization is more than halfway toward its goal of 75,000 signatures.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material that Sightline staff members turn into articles.

Comments are closed.