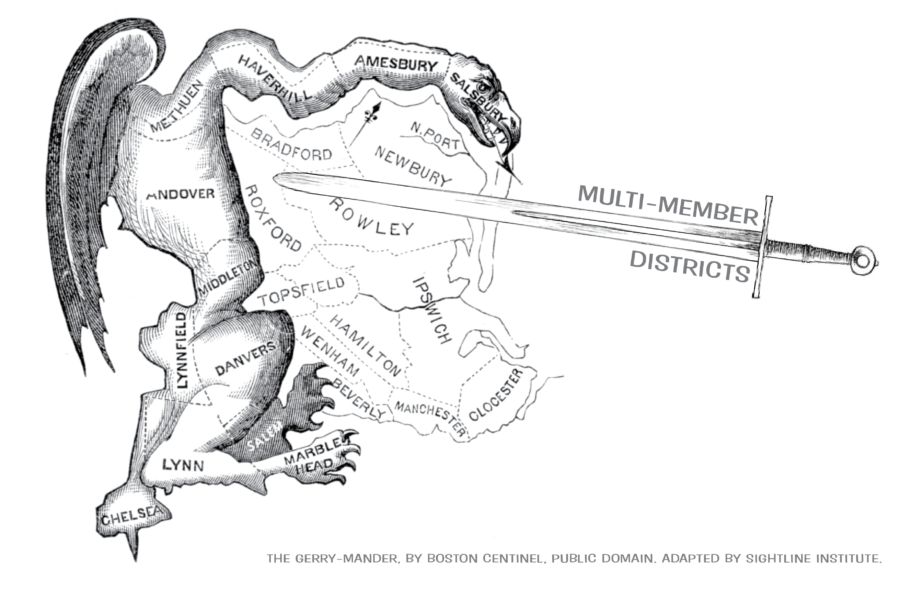

Fortunately, we have a sword that will slice through the heart of the fearsome reptile: multi-member districts.

Everyone hates the gerrymander, a beast named after a salamander-shaped district authorized by Massachusetts Governor Gerry in 1812. Most people agree that voters should choose their politicians, rather than politicians choosing their voters (John Oliver, Eric Holder, and Arnold Schwarzenegger are all anti-gerrymandering). Many anti-gerrymander crusaders hope they can defeat the beast by taking the line-drawing pen away from legislators and handing it to a commission or a computer—someone without a partisan stake in the game. Unfortunately, commissions and computers, though mighty in their ways, aren’t up to the task of slaying the gerrymander. Fortunately, we have a sword that will slice through the heart of the fearsome reptile: multi-member districts.

The gerrymander takes power away from voters and puts it in the hands of whoever draws the district lines. In a representative democracy, voters are supposed to have the power to choose representatives and hold them accountable. But when someone (even a computer program) is holding the pen and drawing a single-winner district map, the line-drawer wields more power than the voters.

Most anti-gerrymandering warriors focus on the perspective of the line-drawers, measuring if they are drawing better lines, often meaning more compact districts. In this series, we take the perspective of the voter, measuring if you have the power to choose who represents you. A voter with the power to choose her representative should be confident that:

- Her vote makes a difference in who gets elected; her ballot has the power to elect an official who represents her and her views.

- Her vote has equal power to every other voters’.

- She can hold her elected representative accountable. She has the power to “throw the bum out” next time around. He knows she has that power, so he takes her calls and responds to her concerns at town halls.

The next three articles in this series will address these voter powers in turn. This article explains why the obsession with whether districts are compact is a diversion from the true battle.

The gerrymander’s dark secret

Most would-be slayers believe they know the beast when they see it—wacky-shaped districts mean gerrymandering is at work while neatly-shaped districts mean gerrymandering is vanquished. If districts look more like docile decahedrons, orderly octagons, or tidy trapezoids than like sprawling dragons, some crusaders are fooled into thinking they have conquered the beast. But the enemy’s real weapon is not the shape of the district but its ability to sap voters’ power.

But when someone (even a computer program) is holding the pen and drawing a single-winner district map, the line-drawer wields more power than the voters.

Here’s something no one will tell you: the fairest single-member districts would be the most “packed” and have the wackiest shapes. You see, the whole idea of single-member districts is that each district encompasses a single community or group of people who have something in common; together they can elect a local representative who is a voice for that shared community sentiment (some redistrictors call these “communities of interest”). The only way to draw single-member districts that live up to this ideal is to shamelessly snake district lines around like-minded households. If a district is so homogenous that 100 percent of the voters prefer the same candidate, the representative from that district would be perfectly representative of every single voter. No voter would feel unrepresented. And together, the perfectly packed districts would elect a legislature reflecting all the voters.

Imagine a city with 100 voters, 54 of whom lean Democratic and 46 percent lean Republican. Voters elect an 11-member legislature. In nearly homogenous districts, almost all voters would feel well-represented by their local representative, and the legislature would reflect the partisan split of voters overall: 6 Democrats (54.5 percent of the legislature) and 5 Republicans (45.5 percent).

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Compare that with supposedly “un-gerrymandered” districts where a computer or commission drew compact districts. In each district, up to half of the voters would not feel represented by their local representative, and the legislature would not reflect the partisan split of the voters overall: 5 Democrats and 6 Republicans (even though 54 percent of voters chose a Democrat).

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Ok, maybe I was exaggerating about no one telling you this secret. Actually, the Republican National Committee’s brief to the US Supreme Court in the much-anticipated upcoming gerrymandering case dedicates an entire section to this point. The brief points out that, if the court adopts a standard for eliminating the “efficiency gap” between which party voters prefer and which party wins the most legislative seats, it will result in “bizarrely shaped districts of the kind this court previously rejected.” You can fix bizarrely shaped districts, or you can fix unrepresentative results. But with single-member districts, you can’t fix both.

Don’t just poke the dragon . . .

Slaying the dragon means giving voters the power to elect representatives who look like them in terms of gender, race, class, and life experience and who will fight for their values, worldviews, and interests. But so long as single-winner districts reign, the only representation you are guaranteed is that one member of the legislature will come from somewhere near-ish to where you live. As long as we have single-winner districts, geographical representation rules. Other types of representation are locked in the dungeons, and our heroes’ hands are tied.

Slaying the dragon means giving voters the power to elect representatives who look like them in terms of gender, race, class, and life experience and who will fight for their values, worldviews, and interests.

Unable to slay the dragon, many gerrymandering opponents settle for trying to poke it into a different shape. By re-shaping the dragon, crusaders can quash blatant partisan power grabs—stopping politicians from intentionally gerrymandering. When partisans hold the districting pen, they can use sophisticated computer models to “pack” the opposition’s voters together into a few safe districts, causing them to waste many votes on already-secured victories, and “crack” like-minded voters apart, spreading them between many districts where they fall just short of victory in every one. Redistricting methods that take the pen away from party operatives can extinguish intentional partisan bias.

Non-partisan redistricting commissions (currently used in California and five other states) could do the trick, as could various computational methods. In Oregon the legislature draws the lines, though the Republican Secretary of State is interested in giving the pen to a non-partisan commission. Idaho, Montana, Washington and the five other states using bi-partisan commissions to draw the maps eliminate one party’s ability to stick it to the other, but they still leave open the door for both parties to stick it to the voters by drawing maps that protect incumbents from both parties. Algorithms for drawing maximally compact districts would eliminate politicians’ ability to intentionally pick their voters, but they would waste many votes and make some votes more powerful than others.

These tools don’t even attempt to broach the bigger task. They don’t protect the voter’s power to make sure her vote matters, that it matters equally to every other vote, and that her elected representative answers to her.

Slay it!

No one—not independent commissions or computers—can draw compact, competitive single-winner districts that give voters the power to elect like-minded representatives and hold them accountable. It is impossible. It’s time to stop trying. It’s time to stop poking the dragon, hoping to prod him into a shape that will magically solve our representation problems. Let’s grab a sword and free ourselves, and end the gerrymander for good. The sword is called multi-member districts.

When voters can elect more than one representative at a time, it doesn’t matter who draws the lines or what shape they form. No seat is safe, voters have a say, and their votes aren’t wasted. I’ll get into the details of these arguments in my next three articles, but for now, just consider this: imagine again that 100-person city electing 11 council members and leaning 54 percent Democratic. But now imagine the council members run in multi-member districts: one district elects five representative, and two districts elect three representatives each. All candidates in a district run against each other, so no seats are “safe” for one party due to intentional or unintentional gerrymandering. Voters rank their candidates in a ballot like this, meaning they can express which of that pool of candidates is their favorite, second favorite and so on. Or they could distribute three votes like this, or vote for one candidate listed by party on a ballot like this. With any of these proportional voting methods, in a district electing three representatives, a group of like-minded voters making up about one-third can elect a representative of their choice (for more about how this works, and examples of how it would play out in Portland, see this article).

For example, in 2016 in Washington’s congressional district 7, voters had to choose between Pramila Jayapal and Brady Pinero Walkinshaw, and no Republican voter anywhere near the Puget Sound area—congressional districts 2, 6, and 7—was able to elect a conservative to congress. Imagine those three districts instead elected three representatives from a single pool and ranked their ballots. Left-leaning voters could have, for example, ranked Jayapal first, Walkinshaw second, Derek Kilmer third and Rick Larsen fourth, and likely two Democrats would have won seats. Republican voters might have ranked Clint Didier first and Marc Hennemann second, and one of them might have won a seat. On a cumulative ballot, left-leaning voters could have given two votes to Jayapal and one to Walkinshaw. In a list ballot, left-leaning voters could have voted for Jayapal and had their vote count for her and the Democratic Party. Or maybe Jayapal would have run under the People’s Party banner. In any case, the Washington congressional delegation would include coastal conservatives and inland liberals, leading to better representation of Washington voters and better ability to work together on solutions.

Representative Don Beyer of Virginia recently introduced a bill in the US Congress, The Fair Representation Act, to require independent commissions to draw multi-member districts and allow voters to rank their choices. This would knock the gerrymander dead for US Representative elections. Though Democrats won just 53 percent of the votes, Oregon’s current map rewarded Democrats with 80 percent of the seats. The Fair Representation Act would give voters the power to correct that imbalance. Washington’s current map locks in representation for the two major parties, but slaying the gerrymander would make the races more competitive and open up the possibility of a third party winning a seat. In both states, more voters would have the power to choose their representative, instead of being stuck in districts that are safe for one major party or the other.

Back to our hypothetical city with 100 voters, if the voters stay the same but instead of 11 single-member districts, an independent commission draws three multi-member districts with one of the voting methods described above, the results could be very different. Some voters who previously felt forced to vote for “the lesser of two evils” between the two major parties might now express their true preferences for the Green Party and the Libertarian party. And all conservative voters and all left-leaning voters would have at least one representative who thinks along the same lines as them, no matter what part of town they live in.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Part 2 in this series shows how single-member districts leave many voters without the power to elect an official who represents them but multi-member districts give voters the power. Part 3 will examine how single-member districts make some votes count more than others but multi-member districts make all votes count equally. Part 4 will look at single-member districts’ lack of accountability.

Together, this series shows that when reformers accept single-winner districts, they have already lost the battle against the gerrymander. The only way to vanquish it for good is to draw multi-member districts that empower voters to elect a representative they like, no matter which district they live in.

Greg Cusack

As always, Kristin, well-argued and clearly-presented — your optics are extremely helpful in clarifying your arguments.

Before coming to Portland, I was a resident of Iowa for 70 years, where I had the honor of serving in the Iowa House of Representatives for 9 of them. For several decades now, Iowa has used a method of reapportioning legislative and congressional districts that could be a model for the nation if, that is, one’s goal is solely — or primarily — eliminating partisan gerrymandering and creating fairly drawn district lines determined by both equality in numbers of citizens in each district and compactness.

This is because the duty of drawing these lines has been turned over to the non-partisan legislative services bureau which is prohibited from receiving any form of “guidance” from the legislature (or individual legislators) whatsoever. Their final map is presented to the Legislature for a simple “yes” or “no” vote. If rejected, they draw another map using the same rigid criteria. This, too, is presented for an up or down decision by the legislature. If this map is rejected, then the legislature has the responsibility for drawing up a third version. This has never happened, as it would be a clear admission of the intervention of partisan politics.

While this system has eliminated gerrymandering, and is tone-deaf to “protecting” incumbents — the new maps inevitably throw several incumbents into the same newly drawn districts — it cannot advance by itself adequately reflect partisan sentiments among the citizens for, while the new districts are certainly “fair” (in that they are not designed to reward any party), they still leave a significant number of citizens in each district effectively without representation: in a district that elects a Democrat, the sizable number of Republicans is left without a voice, and vice-versa for a district that elects a Republican.

It was your research on, and advocacy for, multi-member districts that helped convince me that such districts were clearly the “better” way. They would not only give each district representatives move representative of the diversity of the population in that district, but they would also be much more likely than our current system to promote men and women of more moderate, less extreme, and less ideological positions, a huge benefit in itself.

Thank you for your continued lucid presentations!

Greg

Sharing this with my group and cant wait to see the rest. Aloha!

Kelly Gerling

Alan and Kristin, I love the theory part of the article. And knowing the theory of electoral system design (ESD) is esssntial to being about a transition from oligarchy to democracy in America.

So to implement multi-member congressional districts for the national House of Representatives, how do we get around the two concluding paragraphs of this article?

http://www.centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/articles/multi-member-legislative-districts-just-a-thing-of-the-past/

Kelly

“Unfortunately, commissions and computers, though mighty in their ways, aren’t up to the task of slaying the gerrymander.”

Bullshit. It is perfectly possible to develop algorithms that would solve the issue.

There might still be advantages to MMD even with compactness-based districts. But don’t pretend that MMD are the only way to fix this.

Jeremy Faludi

I love this article–clearly and persuasively argued. A question, though–what’s the downside of proportional representation? There’s a downside to everything, and many countries have proportional representation but still have plenty of corruption (Brazil, Honduras, and a dozen others).

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks for reading, Jeremy. Of course, proportional representation can’t solve all problems, but it does better than majoritarian systems on fairly representing more people, encouraging substantive campaigns, and other things — for more details, see this: http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/18/sightlines-guide-to-methods-for-electing-legislative-bodies/

The main tradeoff between majoritarian and proportional systems is that majoritarian countries govern with a strong but unsteady hand (one party can make decisions when in power, but those policies are often reversed when the other party comes to power), whereas proportional countries govern with a gentler but steadier hand (it takes longer for factions to agree on a path forward, but once they do that policy can stay in place and do its work because most major sectors of society bought it into it and had a hand in shaping it, so no one is hugely angry about it passing).

Sara Wolf

THE DOWNSIDE: STV

This article makes a good argument for proportional representation. There are a few ways to accomplish PR though, not just Single Transferable Vote (STV). For me the downsides in this proposal are that she is recommending we use a RCV ranked ballot. From what I can tell as a non-mathematician who’s done a lot of homework on this, STV is a pretty accurate system that does a good job of giving representative results. On the other hand the single winner version of STV, Instant Runoff Voting or RCV, isn’t consistently accurate, especially in elections with three or more viable candidates. Exactly the scenario we are trying to create by breaking the cage that has us locked in a two party stranglehold.

Of course if we are reforming elections we can’t have one type of ballot for single winner seats and another system for multi-winner seats. That would be confusing for voters.

As it turns out there are versions of STV that can use a 5 star style score ballot. Reweighted Range Voting (RRV) basically works just like STV but with voters able to give each candidate a 5 star rating instead of a ranking, which shows a more nuanced opinion and thus get slightly more representative results. From what I can tell getting accurate results is easier for multi-winner elections than it is for single winner elections so maybe we should pick the best single winner system and then offer the proportional representation system that matches so we can have an accurate and representative package deal!

RRV (or SRV-PR) dovetails perfectly with the new single winner Star Voting system from Equal Vote that is now setting the curve for accuracy, equality, expressiveness and most importantly, making honest voting the best strategy so that voters can safely vote their conscience.

Kristin Eberhard

Hi Sara,

Ranked ballots is one way to get to proportional representation, but certainly not the only way. Cumulative and limited voting can get good results, and New Zealand’s Mixed Member Proportional system could be a good model for Oregon and Washington. http://www.sightline.org/2017/06/19/this-is-how-new-zealand-fixed-its-voting-system/

And there is no reason for everything on the ballot to use the same method. Indeed, since federal, state, county, and city races often appear on the same ballot, the chances of getting them all to switch to the same method at the same time are approximately zero. Using a ranked ballot to get Proportional Representation would not require using rankings for single-winner races.

David Spurr

Terrific piece, Kristin. Thanks for the concise explanations.

Sara Wolf

THE DOWNSIDE: PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION ITSELF

I’m leaning pro-PR but I have heard a few arguments against it that are valid and that are worth considering especially if we do move forward selling a PR system to the public. Here they are in summary.

1. PR can help minority groups like Neo-Nazis come to power when they wouldn’t have had the manpower to get elected in other voting systems. We might be trying to improve representation for ethnic minorities or minor parties but in practice PR systems like STV won’t discriminate so there is a real risk that adding in hateful minorities along with real minority groups could backfire and actually produce less representative legislation. Apparently PR was one factor in helping the Nazi’s gain legitimacy and a foothold and spread their message leading up to WWII. Yikes!

2. There is no good system for measuring how accurate and representative various PR systems are at electing the mix they claim to and the algorithms used for all of them are super complicated. We have Voter Satisfaction Efficiency (VSE) for evaluating accuracy in single-winner systems but the multi winner version is still down the pipeline. This isn’t my main concern though since it *seems* like they are all fairly accurate at what they set out to accomplish.

3. Some people say that broadening the political spectrum of a legislative body, as PR would do, might not necessarily translate to more representative legislation. With the extremes of the political spectrum added in, debate might just get more derailed and politicians might have a harder time coming to compromise in the middle. So PR could lead to more stagnation. I’m not sure if I agree with this point as a valid concern, but maybe?

4. The super complicated algorithms make most PR systems more vulnerable to hacking or fraud or error and would make fraud hard to detect. People can easily understand how to fill out their ballot but actually understanding how the votes are counted is rocket science. It takes pages and pages to thoroughly explain how votes are counted in STV. RRV is less so but still complex because of the reweighing process.

Kristin Eberhard

The myth that PR helped Nazis gain power gets it exactly backwards. PR constrained the Nazis to their proportional share of the vote–37%. Under our majoritarian system, they would have won a majority of seats (just like the Republican party is able to win the presidency and a majority of seats with a minority of the votes). Instead, Hitler was forced to declare a state of emergency and seize power through non-democratic means. More detail here: http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/18/glossary-of-methods-for-electing-legislative-bodies/#multi-winner-score-runoff-voting

Regarding the view that we should block all minorities from seats in the legislature because we are afraid of Neo-Nazis, I disagree. http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/18/sightlines-guide-to-methods-for-electing-legislative-bodies/#proportional-solution-most-voters-succeed-in-electing-someone-they-want-to-office

In short: Blocking everyone with a minority view—whether they be a far-right party, the Green party, or the People Before Profit party—from the legislature is not the most effective method for protecting against extremist views. A strong bill of rights and a just legal system can protect basic rights best. An electoral system that systematically excludes citizens from representation might well lead to the sort of anti-establishment groundswell we’ve seen exemplified in the Brexit vote in the (majoritarian) United Kingdom and the election of Donald Trump in the (majoritarian) United States.

Kristin Eberhard

Re harder to come to a compromise: research shows that PR countries may take longer to find a policy agreement, but once they do more people like it and it sticks (compared to the US where one party tries to fix healthcare and the other party tries to repeal it. PR countries put in place a solution that works over the long term). Interestingly, PR countries have acted faster to legalize gay marriage than have majoritarian countries. Probably because smaller parties introduce new ideas into the public sphere and people talk about them and get comfortable with them. The stodgy two-party system in the US tends to block new ideas. http://www.sightline.org/2017/05/18/sightlines-guide-to-methods-for-electing-legislative-bodies/#proportional-solution-voters-learn-about-and-legislators-craft-innovative-durable-policy-solutions