Representative democracy gives people the power to put their values into action. People can elect leaders who care about the things they care about and then hold them accountable for taking action on those issues. In the United States and Canada, people care about climate change. In Cascadia, people care about protecting their communities from dirty, outdated fossil fuels. So why are elected leaders not aligned with voters on climate change and other issues their constituents care about?

Because the way most North American governments elect executive officers—such as mayors, governors, and the president—doesn’t engage people, doesn’t empower people to vote their values, and doesn’t necessarily elect leaders with broad support. For example, only around 10 percent of US citizens chose Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton in the presidential primaries, leaving many general election voters feeling forced into choosing the “lesser of two evils” rather than participating wholeheartedly in electing a leader they could get behind. In part due to lack of good options on the ballot, ugly, negative campaigns, and the feeling that elected officials don’t represent them, the United States has dismal voter turnout rates.

Could a different way of voting give voters more voice, nurture more issues-driven campaigns, and elect leaders with broader appeal? Which voting systems would give Cascadian reformers better results? This article gives Sightline’s take on what is important in a voting system for electing an executive office held by a single person at a time (like a mayor or governor) and how different voting systems measure up. Although most Cascadian jurisdictions use the same voting method to elect the president and the legislature, the voting system options and considerations for electing legislatures are quite different because more than one person serves in the legislature at a time. (A future article will address voting systems for electing legislative bodies consisting of more than one person at a time—like congress, parliament, state legislatures, and city councils.)

What needs fixing?

The US and Canada use “vote for one” elections that limit voters’ choices and stifle healthy discussion of the issues people care about. Specifically, using the current system to elect mayors, governors, and the president, we suffer from the following problems:

- Voters have to vote for the “lesser of two evils.” You should be able to vote for at least one candidate you support. Yet you must often vote for one of two front-runner candidates and not for a minor-party candidate, or a candidate who was eliminated in the primary, who you like better. You only have one vote, so you grudgingly give it to the least objectionable candidate you know has a shot at winning. When voters feel they don’t have a chance to vote for somebody they support, they may not vote at all. And, as we have seen, not voting can be as significant a move as casting a ballot.

- Unpopular or extreme candidates can win. A candidate vying to be the only person representing a whole city, county, state, or country should have broad appeal. Yet, in the current system, a candidate who is unpopular with a broad share of the electorate can win. He can either split the majority vote and win with a mere plurality (in a three- or four-way race), or he can win over enough of the few, partisan voters who participate in party primaries to become the only viable option on the general ballot in a jurisdiction that is “safe” for his party.

- Personal attacks work better than discussion of issues. Negative campaigning works in our “vote for one” system. Because voters can only express an opinion about one candidate, candidates are rewarded for turning voters off to opponents and aren’t rewarded for reaching out or building bridges to voters who have already chosen another favorite. Negative campaigning amongst a narrow field of candidates means voters don’t hear their issues discussed, and they may find little reason to tune into campaigns and engage in civic life.

Criteria for executive races

Political scientists and mathematicians have come up with many criteria by which to evaluate voting systems, resulting in complex tables like this one. But, unfortunately, no system is perfect. Reformers have to decide what they believe is most important to fostering the healthiest democracy. (Note: The Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance has a tool that translates criteria into priorities and selects the best voting systems for you based on your stated priorities.)

We at Sightline came up with these four criteria to help determine how well a voting system can solve the problems described above:

- Voters have a variety of options: Candidates with diverse views can run, and voters can vote for them without worrying they might be “throwing their vote away” on a minor-party candidate, say. Instead of limiting voters’ options, the election method tends to expand voters’ choices, welcoming more candidates and citizens to participate in elections

- Winners are bridge-builders with broad appeal: A candidate with an energized but narrow base, unpopular with the broader public, can’t win. Instead, the election method tends to reward candidates who connect with a broad swath of the electorate

- Campaigns are positive and inclusive: Candidates’ best strategy is to engage with many voters and discuss the issues that are important to them.

- The change creates momentum for further voting reform efforts.

How each system measures up

Now that we know what principles rise to the top for Sightline, let’s look at how well different election methods do for our four criteria. (If you are unfamiliar with or need a refresher on different types of voting systems before you dive into the analysis below, see our Glossary of Voting Systems for Electing Executive Officers.) We have plenty of empirical evidence for how Plurality, Top-Two Runoff, and Instant Runoff perform in elections. We have some evidence for how Approval Voting performs in student body and professional organization elections, but unfortunately, we have little or no evidence of how Score and Score Runoff perform, so we must speculate based on the systems’ characteristics.

(Click on the headings below to expand or collapse the discussion of each criterion.)

The most common voting systems in place in the US and Canada today are Plurality (vote for one, and the candidate with the most votes wins) and Top-Two Runoff (vote for one in the primary; the top two advance to the general; vote for one in the general election).

Additional candidates, beyond the two major-party mainstays, might appear on a Plurality ballot, but they usually receive very few votes because voters don’t want to throw away their only vote or spoil the election for their preferred major-party candidate. American voters all know how this works: if a majority of voters prefer both Nader and Gore to Bush, but split their votes between Nader and Gore, then Bush could win with a plurality (more votes than any other candidate, but less than half the votes). So voters cast their one vote for Gore, and Nader wins very few votes and often doesn’t even run.

Under Top-Two Runoff, voters see just two candidates on the general election ballot. The general election campaign is usually exclusively shaped by the two major parties, with no opportunity to bring other viewpoints into the discussion. Because they can’t make it to the general election, Top-Two Runoff discourages additional candidates from participating even in the primary.

Other voting systems allow more candidates to appear on the ballot and allow voters to express opinions about more than one candidate. However, only one makes it safe for voters to express an opinion about multiple candidates. Instant Runoff Voting (a single-winner form of Ranked-Choice Voting) lets voters rank candidates in order of preference on a single ballot and then simulates a series of runoffs. Under Instant Runoff Voting, it is safe to rank a weak third-party candidate like Nader (a third-party candidate who is in third or lower place). If you rank him first and he is eliminated, your vote transfers to your next-ranked candidate who is still in the running.

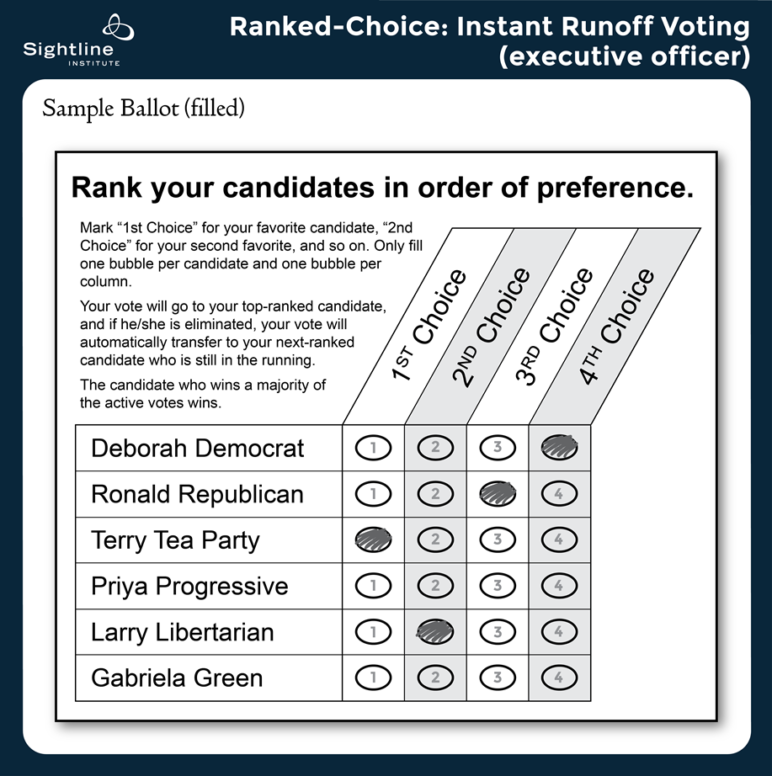

For example, say you ranked Terry Tea Party first, Larry Libertarian second, Ronald Republican third, and, just in case, Deborah Democrat fourth. Your vote would count for the Tea Party candidate in the first round; if she was eliminated, your vote would transfer to the Libertarian if he was still in the race; and if he was eliminated, your vote would transfer to the Republican if he was still in the race (probably, since he is a major-party candidate). If, by chance, the Republican had also been eliminated and the Democrat was running off against the Progressive, your vote would go to the Democrat. Or, if you ranked the Republican first, your vote would count for him in every round so long as he was not eliminated.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

IRV can create a “center squeeze” situation where a candidate in the ideological center (likely a major-party candidate) could have won if a candidate to one side of him had not run, but because he ran, the candidate on the other side won. The one time this happened, in Burlington, Vermont, the Republican (on the right) and the Progressive (on the left) got the first and second most votes while the Democrat (in between them) in third place was eliminated. In the runoff between the Republican and Progressive, the Progressive won. But if the Progressive or the Republican had not made it to the runoff, the Democrat would have won against the remaining candidate. For example, if Republican voters who preferred the Democrat over the Progressive (about 17 percent of Burlington voters) could have somehow known that the Republican, who was polling in first place in a plurality election, would lose to the Progressive once the Democrat was eliminated, they could have strategically ranked the Democrat first to help him, not their favorite the Republican, make it to the runoff and beat the Progressive.

Because this situation rarely occurs (once in 142 US elections that release full data—0.7 percent of US elections—and no reports of it happening in a hundred years in Australia, though they don’t release full data so it is impossible to know for sure); and because it is difficult for voters to know ahead of time that their favorite, who is polling in first or second place, will lose; and because it is unlikely that voters will abandon their favorite and instead vote for a less-preferred candidate who is trailing in the polls; and because the candidate they would betray is a strong candidate—in first or second place—and the candidate who gets squeezed out is likely a major-party candidate; the center-squeeze situation is unlikely to discourage additional candidates from running in IRV elections or voters from voting for them.

The center candidate risks being squeezed out in any runoff system. If Burlington had used Top-Two Runoff, the Democrat would not have made it to the runoff. If it had used Score Runoff, he might not have made it to the runoff if Progressive or Republican voters had given him low scores (an average of 1.3 or lower) to protect their favorites.

Score Runoff Voting, Score Voting, and Approval Voting all let voters give each candidate a score. In Score and Score Runoff Voting, possible scores might range from 0 to 5, 0 to 9, or some other range, and all the scores are added or averaged. Under Approval Voting, the score is implicitly a 1 or a 0 because it is a vote or no vote; the ballot looks just like a Plurality ballot except you can vote for as many candidates as you want. Bucklin Voting uses a ranked-choice ballot but adds votes together like Approval Voting. All of these systems are flawed because they do not support what voting experts call “Later-No-Harm”: you can harm your favorite candidate by giving any other candidate a score or vote. When voters realize this, they often “bullet vote” (only score or vote for one candidate). If voters know which candidates are viable and which are not, they might vote for their favorite of the viable candidates and also any other candidates they like, so long as they are sure those other can’t beat their favorite.

Experience suggests that most voters using Approval and Score give their favorite candidate the maximum score or rank and all other candidates a minimal score or no vote. Candidates beyond the two major parties would likely not get many votes in these systems. Voters could figure out it is safe to give a minor-party candidate a vote or score as long as you are sure she will lose. But the major parties would encourage voters to bullet vote, and, to reassure voters it is safe to vote for them, minor-party candidates would have to convince voters they are sure to lose, which is a dog of a campaign strategy.

Score Runoff Voting should, in theory, encourage voters to give a maximum score to their favorite and also a score to their second-favorite, so that if their favorite is eliminated they could still get a vote for their second-favorite in the instant runoff. This would allow for a broader field as candidates ask voters for their maximum or a back-up score.

No single person can perfectly represent all the people in a city, state, or country. In other words, there is no perfect winner for an executive office held by just one person at a time. Different people have different ideas about who the “most right” winner is. The candidate whom a majority of voters support? The candidate whom most voters would choose over any other individual candidate in a head-to-head race? The candidate the fewest voters strongly object to (even if that also means that fewer voters strongly support him)? The candidate whom voters most strongly adore, even if many voters object?

No voting system can guarantee the winner is all of the above. For Sightline’s purposes, let’s set a lower bar: an unpopular or extreme candidate can’t win and become the only president, governor, or mayor for an entire country, state, or city. In this context, the definition of unpopular or extreme is: a candidate a majority of voters don’t want. One way of measuring this is that a majority of voters prefer every other candidate above this one (voting experts call this the Majority Loser criterion). Another measurement is that the candidate would lose to every other viable contender in a head-to-head contest, meaning a majority of voters would prefer any of the other candidates over him (voting experts call this the Condorcet Loser criterion).

If a voting system allows a candidate to win even if a majority of voters didn’t want him, it encourages candidates to fire up a narrow base of supporters while ignoring the majority of voters. This can lead to a divisive governing style and discontent with a system that would deliver such an unrepresentative executive. If a voting system guarantees that candidates without broad appeal cannot win, it encourages candidates to reach out more broadly to win over a majority of voters, as well as to govern more moderately, with the majority of voters in mind.

Instant Runoff Voting, Top-Two Runoff, and Score Runoff Voting meet the Majority Loser and Condorcet Loser criteria: they will never elect a candidate whom a majority of voters did not want or one who would lose to every other candidate in a head-to-head. The final head-to-head runoff in these three systems protects against an extreme candidate. However, in jurisdictions that hold party primaries and are “safe” for one party, an extreme candidate could win his party’s primary and then go on to win the Top-Two Runoff general election because voters are loathe to vote for the opposing major party. If instead Instant Runoff Voting or Score Runoff Voting were used in a single, high-turnout general election, it would elect a leader with broad appeal.

Plurality, Approval, and Score Voting fail both the Majority Loser and Condorcet Loser criteria: they can elect a candidate whom a majority of of voters did not want. In Plurality voting, this happens when the majority of voters split their votes between two similar candidates and the third, least popular candidate, wins with a mere plurality of the vote. The same can happen if most voters bullet vote in Approval Voting. Score Voting is, in a sense, designed to elect (this definition of) an unpopular or extreme candidate because it values intensity of preference over numbers of voters: a minority of voters can elect their favorite, even though he lacks broad appeal, by giving him a maximum score, beating the more broadly appealing candidate who received less than maximum scores from a majority of voters.

Bucklin passes Majority Loser but fails Condorcet Loser.

Negative campaigns don’t invite citizens to participate in civic discourse, and they take up airtime that could otherwise be spent discussing issues that are important to voters. Negative campaigns have other insidious negative effects, such as dissuading women from running for public office. To encourage positive campaigns, a voting system must reward candidates for reaching out to many voters, including those who might already prefer another candidate. Voting systems reward negative campaigns when a candidate can win by whipping up a narrow base of support, or can increase his chances of winning by insulting opponents.

Plurality Voting rewards negative campaigns because, to win, a candidate only needs to energize his or her base, not appeal broadly to a majority of voters.

Instant Runoff Voting has proven to produce more positive, civil campaigns. Because candidates can benefit from receiving second- or third-choice rankings, it is in their interest to court their opponents’ voters rather than ignore or alienate them. (Watch Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges explain in this video.)

Approval Voting could discourage negative campaigns as candidates urge voters to include them as one of several candidates they vote for. However, as discussed above, voters can harm their favorite by voting for additional candidates, leading to the real-world experience that Approval Voting ends up looking a lot like Plurality Voting. So candidates might campaign just like Plurality.

Score Voting could lead to even more negative campaigns than Plurality Voting. Like Plurality Voting, Score Voting rewards candidates for energizing their base, but it additionally rewards candidates for provoking lower scores for their opponents. A candidate could win a campaign under Score Voting by whipping her the base into a frenzy of maximum scores while sowing doubts amongst her opponents’ supporters. Rather than moderating her message to win scores from more voters but risking alienating her base, she can focus on tearing down her opponent to both fire up her base and undermine other voters’ confidence in their candidate enough that they give that other candidate less than the maximum score. Score Voting could prompt a race to the bottom in terms of negative campaigning.

Score Runoff Voting, a hybrid of Score Voting and Instant Runoff Voting, would likely be somewhere between the two in terms of campaign tone. Because voters would want to give some non-zero score to candidates other than their favorite, it would be in a candidate’s interest not to alienate her opponent’s voters in hopes they will give her a score. But as in Score Voting, a candidate could be harmed if her voters give another candidate a score, so she would want to encourage them to give her the maximum and give her opponents a minimum score, creating an incentive for painting her opponent in a negative light.

Any reform must overcome the inertia of the status quo. Any reform that gives minor parties more power risks pushback from the two major parties. Facing into these headwinds, reformers need to know that each hard-fought win will build momentum for the next.

In the United States, Ranked-Choice Voting is the only voting reform with momentum. Thirteen US cities and counties already use it; the state of Maine just adopted it for state and federal elections; and here in Cascadia, Benton County passed an Instant Runoff Voting initiative in 2016. In 2017, 18 states have introduced ranked-choice voting bills—11 states have Republican co-sponsors, and 13 states have Democratic co-sponsors.

Instant Runoff Voting (a.k.a. single-winner Ranked-Choice Voting) can also build momentum towards a more powerful reform—proportional representation in multi-winner elections. As more American voters become familiar with a ranked-choice ballot, it could make it easier to introduce the system into a multi-winner ranked-choice election (a.k.a. “Single Transferable Vote”)—more on this in our Guide to Voting Systems for Electing Legislative Bodies, publishing next week.

Score Runoff Voting is building momentum in Oregon. It also has a multi-winner form, but it may not achieve as fair results as multi-winner ranked-choice voting—more on this in our Guide to Methods for Electing Legislative Bodies,.

Conclusion

Based on what’s currently failing or out of balance in executive elections in the United States and Canada, Sightline judges Instant Runoff Voting as currently the best reform to pursue. It allows a diversity of candidates from major and minor parties to run and win votes. It nurtures more positive campaigns. It rewards candidates for building bridges to many voters and blocks extreme candidates from becoming the only mayor or president that a city or country has. And it has momentum in the United States.

Score Runoff Voting deserves experimentation to see how it performs in the real world.

Top-Two Runoff and Approval Voting offer improvements over Plurality Voting, but not as much improvement as Instant Runoff and Score Runoff.

Plurality Voting is clearly an inferior option on every criteria. Score Voting also seems particularly undesirable, because it might incentivize even more negative campaigns and result in divisive, extreme candidates winning office even more often than does Plurality Voting.

Our current “choose one” method of electing mayors, governors, and presidents is fraught with problems. But Ranked-Choice Voting, and possible Score Runoff, could give voters more options on the ballot, elect executives with broad appeal, and generate more positive, issue-oriented campaigns.

A note about partisan gridlock, sound policy-making, and reflective representation

Astute readers may note that the criteria above do not address the pressing problems of overcoming partisan polarization and gridlock, electing more diverse representatives, and fostering problem-solving and sound policy-making. Sightline passionately believes in reforming voting systems to solve these problems. They all fall within the provenance of the legislative branch, and we discuss them in our forthcoming Guide to Methods for Electing Legislative Bodies for electing multi-seat legislative bodies such as federal, state, and provincial legislatures and city and county councils. Better voting systems for electing legislative bodies can elect diverse bodies that reflect all voters, incentivize consensual problem-solving over partisan gridlock, deliver broadly supported policy solutions, and help strengthen civic life.

Jan Steinman

I’m mystified by your assertion, not explained fully here, that proportional representation is the highest form that “possible” interim solutions (like IRV) are but stepping stones toward.

It seems to me that proportional representation very much supports the party system, which itself is responsible for much polarization. It appears that prop-rep tends to elect candidates that do not necessarily represent constituents, but rather it elects candidates that represent a national party platform.

In the US, representatives typically represent constituents, and a Democrat in Georgia might be more “right” than a Republican in California, or a Republican in Oregon (Tom McCall and Mark Hatfield come to mind) might be more “left” than a Democrat in Alabama. This means that national policy must truly be a compromise, because having a party majority is no guarantee that every representative will find a policy to be in their own constituents’ best interests.

In Canada, prop-rep would arguably result in much less constituent representation, since party votes are often “whipped” so that all party members must vote a certain way, regardless of the desires of their constituents.

I think that a large, multi-cultural country, such as Canada or the US, needs democracy that represents constituents, rather than parties. Prop-rep democracy in diverse countries will still end up as two wolves and a sheep, voting on what’s for dinner.

Prop-rep may work well in countries with smaller populations and less diversity, but we should not let its success in places like Germany and England make us believe that it is the best thing for North America.

Kristin Eberhard

Hi Jan,

Thanks for reading. If I understand correctly, I think you are concerned about a particular form of Proportional Representation called Closed Party List Voting, where voters choose a party and the party chooses all the legislators. I agree that system, especially if the parties were national with no regional or local representation, would not be a good solution for national elections in a big, diverse country like the US.

However, there are other forms of Proportional Representation that would work well here. Please come back next week for two articles about all the options! But in the meantime, you can see some examples of how PR could work for state legislatures in OR and WA here: http://www.sightline.org/2016/05/02/three-ways-oregon-and-washington-could-vote-better/

Also, I think it is the fact that two parties dominate in the US that leads to party polarization, not the existence of parties at all. Parties should simply be a way for like-minded people to organize themselves, have a voice, and contribute to policy solutions. For more about the problem of polarization and how an American form of PR could solve it, I recommend this article: https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/4/26/15425492/proportional-voting-polarization-urban-rural-third-parties

Kelly Gerling

If a referendum vote for an executive with a top-two runoff favors two major parties, how did the recent French presidential election show otherwise?

What is the effect with IRV/RCP denying a debate between the top two as the French election allowed?

What do you think about an option not mentioned: electing executives out of a dominant coalition in a parliamentary system? I know many Americans who prefer that, including economist Michael Hudson.

Kristin Eberhard

Hi Kelly — My understanding is that the French election, sort of like the 2016 US presidential election, was a bit of an anomaly reflecting public unrest. Past French president usually came from one of the two major parties.

IRV with, for example, a top-four primary in the US presidential election would allow more Americans to hear about more policies during the debates. Imagine if Bernie Sanders had been on the stage during the debates–we would have heard about more issues that are important to voters.

I’m a fan of the parliamentary system! But that would not involve a public election, so these systems would not be relevant.

Sara Wolf

“If people in the reform community spend energy tearing down those who are fighting for reform…” -Kristin Eberhart

Kristin, this gets to the heart of the problem. Reading your article and response to Clay’s concerns on Loomio shows that you are taking the feedback about IRV and these concerns personally. Please don’t! You’ve put a lot into supporting IRV in your career but as election science evolves and new solutions emerge it’s important to look at these systems objectively. Reading this article *feels like* you are trying to mischaracterize SRV (Star Voting). As you know there is a scientific system that can measure voting system’s relative accuracy across all criteria. This is called Bayesian Regret and the inverse, Voter Satisfaction Efficiency (VSE). Omitting this key information makes no sense in a guide to comparing voting systems. Why do it? Condorcet and VSE are the two best tools we have for establishing measurable accuracy. Accuracy is our most important criteria for a new voting system.

Saying that in SRV people would “bullet vote” and only score their top 2 makes no sense for tons of reasons and scenarios I’m sure you are aware of.

“Later No Harm” is a criteria that I disagree with because it directly prevents a voting system from electing a strong compromise candidate if there is no strong majority winner candidate. That is a negative outcome for the electorate and I believe we should revisit this criteria. The ideal here should be that a voter doesn’t hurt the best possible outcome for the electorate as a whole by honestly rating or ranking the candidates. If voters honesty show that they would be okay with a candidate other than their favorite and show how much they would support that candidate and under which circumstances, that is a good thing. This is a key tenant of consensus decision making and is one of the reasons that SRV (Star Voting) is able to out preform IRV in situations where there is not a simple majority winner with just the first choice votes counted.

Many of us think the inverse of “Later no harm” is a better criteria and that it should be called something like “Compromise Criteria”. That a voting system should allow and encourage voters to express themselves with enough detail to help find the winner that can make as many voters as happy with the outcome as possible. This is what SRV (Star Voting) offers and this is one reason that it outperforms IRV in Voter Satisfaction Efficiency (VSE).

The other reason SRV (Star Voting) outperforms IRV in VSE is that in IRV if your 1st choice is eliminated in a later round your other rankings may never be looked at. Ignoring some of the voters preferences on the ballots directly causes less accurate results.

At Equal Vote we compare voting systems using 6 criteria. Accuracy, Honesty, Equality, Simplicity, Expressiveness, and Viability. http://www.equal.vote

Clay’s point by point critique of this article can be found here. Clay Shentrap is a co-founder of the Center for Election Science: https://www.loomio.org/d/IhpoMgkt/new-sightline-article-by-kristin-eberhard

Kristin Eberhard

Hi Sara,

Thanks for your comment—I think it actually underlines what I said in the article: no system is perfect, so people will reach different conclusions based on what is most important to them.

This article lays out explicitly what is important to Sightline. Different things may be important to you, or to others. For example, you and others find “utility,” the philosophical basis of the Voter Satisfaction Efficiency model, to be important. In a voting system, “utility” means that some voters count more than others if they feel more intensely about their opinions. This is a perfectly valid model in other contexts, for example when choosing where to go to dinner it should matter more that the vegetarians in the group would intensely prefer a place with vegetarian options. But when electing a president or governor or mayor, I don’t think a small group who feels intensely should count more than other voters. You and other fans of VSE disagree.

As the article says, Sightline cares about a variety of candidates running for office and running civil, positive campaigns. VSE explicitly states that it cannot measure who decides to run for office nor can it measure effects on campaign behavior. So it is not mysterious why I didn’t rely on VSE: it measures something I disagree with in this context and doesn’t measure the things I care about. Just because something uses math doesn’t mean it is the objective truth; models are based on assumptions and value judgments, and the article is clear about what those are for Sightline.

You don’t like the “Later No Harm” criterion because you believe that voters will vote in a way that allows for the best outcome for the electorate as a whole, even if that hurts their personal favorite candidate. The evidence I have seen suggests that when the stakes are high, people most voters won’t vote for (or give an honest score to) a compromise candidate if they know that vote (or score) will hurt their favorite.

And, btw, I have not spent my career promoting IRV. I’ve spent my career fighting climate change. As it became clear that climate action, and other popular and broadly beneficial actions, were blocked by broken institutions of governance, I started working on democracy reform. Last year I did a lot of work on money in politics, as well as automatic voter registration and the electoral college, and now I am working on voting systems. These articles reflect my deep dive into what researchers, advocates, and experience says about each system. I came to it with an open mind. I was initially interested in score voting—one of the first things I read was Gaming the Vote, at Clay’s suggestion. But my conclusion, based on my research and Sightline’s values, is what’s published in this article. IRV has a track record of performing well in single-winner elections and momentum in North America, so we support its spread. SRV seems like it would perform well, so we support SRV getting some actual election experience.

Clay Shentrup

> Sightline cares about a variety of candidates running for office and running civil, positive campaigns.

Kristin,

Would you rather have a civil campaign with Trump/Duterte winning, or a negative campaign with Angela Merkel (or Trudeau or Macron) winning?

My point is, it should be obvious that election _outcomes_, which affect years’ worth of policies, are vastly more important than the nature of political campaigns. And that’s what VSE measures—voters’ satisfaction with outcomes. Of course they are imperfect models of a complex world, but they are quite robust and fill a huge missing gap that cannot be addressed through empirical means (because you can’t precisely measure or quantify real humans’ utilities).

Of course we want _substantive_ and _policy-focused_ campaigns (though whether they are “negative” is IMO far less important). But there are sound reasons to expect that virtually any alternative voting method will help in this regard, as well as with the issue of having a diversity of options, by addressing vote splitting.

> You don’t like the “Later No Harm” criterion because you believe that voters will vote in a way that allows for the best outcome for the electorate as a whole, even if that hurts their personal favorite candidate.

No, that’s not the argument Score Voting advocates are generally making at all. Warren Smith has specifically addressed Later-no-harm in great detail here, albeit in a harsh critical tone. I’ll try to put that into layperson speak.

The Later-no-harm Criterion is badly misnamed, because the “harm” is harm to a voter’s favorite candidate, to the voter per se. But voters care about harm to _themselves_, not necessarily to any particular candidate—even their favorite candidate. This is massively evident from our experiences with Plurality Voting, in which voters often betray (i.e. intentionally harm) their sincere favorite in order to maximize their own expected happiness by helping to get an “electable” candidate they can at least tolerate. The canonical oft-cited example is the Nader supporters who voted for Al Gore in an effort to prevent Bush from winning in 2000. This “spoiler” scenario is precisely what IRV proponents (including you) often cite as a major cause to support IRV.

To make this concrete, imagine a voter who’s honest rating for some of the recent Seattle mayoral candidates is as follows: Jessyn=5, Durkan=3, Moon=2, Oliver=0. Assuming she can pick up on the fact that Durkan and Moon are the frontrunners, what should her strategy be? Under the status quo, she wants to vote for Durkan. This STRATEGIC VOTE means she _actively harms_ her favorite. Okay?

So now, what should she do with Score Voting or Approval Voting? The optimal strategy is rather complicated (you’d want a calculator), but to a close approximation, it’s simply to push Durkan and Moon apart like beads on an abacus, so that the strategized ballot becomes: Jessyn=5, Durkan=5, Moon=0, Oliver=0 (or just approve Jessyn & Durkan with Approval Voting).

Now, notice how the voter had absolutely no reason not to support her sincere favorite, Jessyn? This ability to essentially support anyone you prefer to your favorite frontrunner is part of what makes Score Voting and Approval Voting so resistant to strategic behavior. We say that these systems satisfy the (much more important) Favorite Betrayal Criterion. And to reiterate the obvious, it is absolutely not the voter’s best strategy to “bullet vote” only for her favorite, same as with the Plurality Voting system we have now.

Now what is the voter’s best strategy under IRV? She still wants to maximize Durkan’s advantage, by giving Durkan the greatest support possible. But because IRV doesn’t allow equal rankings, this means she’s strategically forced to move Jessyn down to 2nd place. The math is quite simple: If the voter believes Jessyn has little chance of winning, then she knows Jessyn is more likely to be a spoiler (like the Republican in Burlington, VT’s last IRV election) than to win.

So upon correct analysis, Score Voting and IRV actually perform in the exact same way than the misleadingly named Later-no-harm Criterion would lead people to believe. And no, we are not saying that Score Voting relies on selfless angels, who sacrifice themselves for the greater good. We are saying that Score Voting works well in a situation where voters are being optimally strategic, just like those Nader-betrayers were with Plurality Voting. And due to the same underlying strategy of voting for one’s favorite frontrunner as the first priority.

Now in addition to all this, it’s been shown that a sincere Score Voting ballot has about 91% as much power as an optimal strategic vote (using a calculator). And it requires no math. So actually, we can expect a lot of voters to lazily-strategically cast sincere Score Voting ballots, just as a lot of IRV users do.

Clay Shentrup

> when electing a president or governor or mayor, I don’t think a small group who feels intensely should count more than other voters. You and other fans of VSE disagree.

I hate to violate some analog of Godwin’s Law here, but think about slavery. If a majority wants to enslave the minority, that doesn’t make it good. Because the utility benefit to the majority will be small compared to the harm caused to the minority. Again, all throughout public policy we see clear examples of the fact that people really are utilitarians when the rubber meets the road.

Further, it’s amazing how immune you are to the basic fact, that has been pointed out to you on numerous occasions, that this is mathematically proven. I repeat, mathematically proven. See yet another example here.

http://scorevoting.net/XYvote.html

Clay Shentrup

And to really twist the proverbial knife on this particular point, bear in mind that IRV can elect X instead of Y, even in cases where Y gets more first-place votes than X _and_ is preferred to X by an arbitrarily large majority.

So, please. Let this majority rule point go. It’s a paper tiger.

Aaron Wolf

Kristin,

You wrote:

> The evidence I have seen suggests that when the stakes are high, people most voters won’t vote for (or give an honest score to) a compromise candidate if they know that vote (or score) will hurt their favorite.

Could you please clarify what that evidence is? It’s directly opposite to the evidence I’ve seen, and I’d like to broaden my perspectives.

From my view, it seems far more people betray their favorite (e.g. Nader in 2000) in order to vote for the more viable lesser-evil. The number of voters who refuse to betray their favorite because they care most about expressing their support of their favorite seems far far smaller from what I’ve seen.

Sara Wolf

Re: “For example, you and others find “utility,” the philosophical basis of the Voter Satisfaction Efficiency model, to be important. In a voting system, “utility” means that some voters count more than others if they feel more intensely about their opinions.”

Absolutely not! IRV plays favorites by not counting some voters down ballot rankings. Irv favors those that prefer the non-viable extremist candidates or the front runners while putting viable underdog voters at a real disadvantage. STAR Voting (SRV) takes all of the rankings into account and gives everyone an equally weighted vote. You are way off base here.

Sara Wolf

Here is a link to my article draft that looks at leading voting systems and gives the pros and cons of each.

https://wordpress.com/post/dreamtimecompass.wordpress.com/1120

Sara Wolf

Please also see “The Quest for Election Reform: Comparing Voting Systems”

https://dreamtimecompass.wordpress.com/2017/02/24/the-quest-for-election-reform/

Clay Shentrup

> when electing a president or governor or mayor, I don’t think a small group who feels intensely should count more than other voters.

This is well trodden ground, and all I can say is that this intuitively sensible view doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

First, it’s logically proven that intensity of preference has to matter. This stems from some unassailable axioms like Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives. This is so counterintuitive that it essentially won Kenneth Arrow the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Another example: it’s possible for a majority of voters to want referendum X to pass, and to want referendum Y to pass—even though a majority of voters would rather have NEITHER pass than have BOTH pass. You might shake your head in disbelief at that, but that link shows a simple proof of concept.

When people say they believe in “majority rule”, they generally have no idea about these logical pitfalls. They think they’re holding a logically tenable position, but they’re not.

Second, most people readily acknowledge the need for “anti-majoritarian” outcomes that help the greater welfare. At the risk of violating something akin to Godwin’s Law, consider slavery. If 90% of voters want to enslave the other 10%, we generally accept that this would be a moral atrocity. To the utilitarian, this is obvious: The harm caused to that 10% vastly surpasses the marginal benefit caused by the leisure afforded to the other 90%.

Third, just practically speaking, what are the odds that an unambiguous majority-favorite candidate would lose with Score Voting? Vanishingly small. So for all intents and purposes, this is academic. Meanwhile, there are much more practical issues where Score Voting excels, like precinct summability, compatibility with existing voting machines, transparency of results, spoiled ballot rates, ease of escaping duopoly, etc. So it’s hard to give much credence to these majority rule concerns.

Clay Shentrup

> You don’t like the “Later No Harm” criterion because you believe that voters will vote in a way that allows for the best outcome for the electorate as a whole, even if that hurts their personal favorite candidate.

Suppose the obvious frontrunners are X and Y, and I prefer the candidates in this order: WXYZ.

With Plurality Voting (the status quo), my best strategy is to vote for X.

With Approval Voting, my best strategy is to vote for X and W.

With Score Voting, my best strategy is to give X and W a 10, and Y and Z a zero.

With IRV, my best strategy is to vote: XWYZ — though many voters will intuitively push Y all the way down, creating XWZY.

This shows that “Later-no-harm” is a red herring. LNH says that ranking X after W can’t hurt W. But that’s irrelevant here, since the best strategy is to rank X ahead of W.

> The evidence I have seen suggests that when the stakes are high, people most voters won’t vote for (or give an honest score to) a compromise candidate if they know that vote (or score) will hurt their favorite.

With our present choose-one system (Plurality Voting), this should be even more true, and yet we all know that “strategic voting” means voting for someone who is not your favorite. So I don’t know what evidence you could be referring to.

Sara Wolf

Thanks for the work you are doing on election reform and have done on climate change! A few clarifying points:

1. I have huge respect for people who have spent years working on IRV! Until there was a clearly better option IRV was my preferred system too. It was the best we had IMO. Star Voting (SRV) is brand new and solves a lot of the major complaints with both Score and IRV that came before so I want people to get where it doesn’t fall into the same old pitfalls and not lump the good in with the bad.

2. Star Voting (Score Runoff Voting) and Ranked Choice Voting (IRV) *both* do a great job of encouraging positive campaigning and outreach to other candidates supporters!

3. About VSE: VSE is about measuring overall voter satisfaction with the election result and asking the question “is there another winner that the people would have been happier with?” I think that the big picture is the best perspective for looking at overall accuracy in an election. That in NO WAY means that we value some voters over others! That is NOT what I’m saying and that’s NOT what VSE or Utility means. That’s NOT what it means to accept that some degree of compromise in an election system might be a good thing.

Star Voting (SRV) is *specifically* all about giving every voter an Equal Voice and making sure we have a voting system that doesn’t favor some voters or candidates over others! Every ballot has equal weight in that for every vote I cast you could vote in an equal and opposite way. This is the legal definition of Equality in voting and this key principle is the reason that our group is named Equal Vote!

IRV doesn’t fully meet Equality criteria and the fact that some voters rankings are never looked at while others have all their ranking counted means that IRV gives some voters more voice than others. This is the root of my problem with it and also the root of the Spoiler Effect in IRV. It’s important to note that this spoiler (split vote) effect in IRV isn’t just a center squeeze effect. It can happen to any viable candidate if there are 3 or more strong contenders.

4. Just as we use VSE and Condorcet for an overall perspective we look at other criteria for a voters perspective. Later-no-harm (LNH) states that a voter shouldn’t hurt their favorite by giving some support to another. This is an important concept to look at, it just isn’t a black and white idea that is all good or bad. Since there is no perfect system where 100% honesty is always the best strategy, Honesty and LNH are at odds. You can’t be perfect at both. Star Voting does a good job with LNH, it’s just not 100%. It encourages voters to give honest ratings to all the candidates because this helps them have a say in the runoff if their favorite doesn’t make it that far.. even though it could help another knock their favorite out of the runoff. The thing is that if their favorite didn’t have enough support to make the runoff they didn’t have enough support to win. This honest rating is a trade off that sacrifices basically nothing (since voters aren’t all knowing and can’t know the slim edge cases where they could/should be slightly less honest or more strategic,) but then this honesty creates huge gains in honest voting and overall best outcomes!

In order to find the best winner overall we need to have all the info from every voters honest opinions. I want a voting system that does the best possible job of encouraging voters to give us that information and then does the best job of taking all that and finding the best winner! We use 6 criteria: Accuracy, Honesty, Equality, Simplicity, Expressiveness, and Viability. For me personally Accuracy, Honesty and Equality are the most important and a voting system should be as perfect as possible. The other three are important to but don’t have to be near-perfect to be good enough.

Saying that you don’t like VSE because it doesn’t measure positive campaigning is like saying you don’t like your speedometer because it doesn’t measure RPMs. I’m not saying that VSE is the *only* thing that should be looked at here, but we can all agree that accuracy and electing the candidate preferred by the people is a key goal for any voting system. It should be at least considered and mentioned! In the *vast* majority of cases VSE and Condorcet agree on who the best winner is. I’m gathering that you don’t like either?

So if you made it this far Kristin thank you! Sorry to be so long winded. I hope that I’ve cleared up some big misunderstandings and that we can understand each-others positions better for it by the end of this thread. Looking forward to working together on this! Appreciate you!

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks, Sara, for all your work on electoral reform.

I’m not sure what you meant when you said “the legal definition of Equality in voting” is “every vote I cast you could vote in an equal and opposite way.” Because that is not the legal definition in the sense of the definition that the American legal system uses.

In courts, equality is measured by “one person, one vote” and IRV meets that definition. Two state courts and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (which covers Oregon) have upheld IRV because of the fact that IRV only counts one vote per person per round. One vote per person per round is the thing that makes IRV legal, and that makes it safe to rank additional candidates, but it is also the thing that advocates for Score, Approval, and Score Runoff don’t like about it. Those methods all count up all preferences at once which, if everyone votes honestly, gives a more accurate overall picture of preferences, but it is also the thing that makes it unsafe to score additional candidates and makes it questionable whether it would be upheld in court unless someone can convince the courts to abandon their current definition of “one person one vote” and adopt your definition instead.

I agree with you that “electing the candidate preferred by the people is a key goal,” but as the previous article and all this discussion make clear: when there are more than two strong candidates, it is not at all straightforward to figure out who that is! There are many approaches to figuring out who the people “prefer.” Condorcet is one reasonable approach, but none of the methods guarantee the Condorcet winner, and VSE doesn’t even agree that the “right” winner is always the Condorcet. In 99.3% of actual public elections in the US using IRV, the Condorcet winner won. Majority and Mutual Majority are other reasonable approaches to figuring out who the people prefer, and IRV guarantees majority winners will always win, but SRV does not. VSE offers another approach: assume that people’s preferences are based on fixed policy positions—each voter has a fixed position on a range of policies and each candidate has a fixed position, and the “right” winner is the one with the smallest mathematical distance between their policy coordinates and the voters’ average policy coordinates. I find the set of assumptions to be questionable (voters have fixed policy preferences? Why did Republicans, who were previously opposed to cozy relations with Russia, suddenly change their mind? Because politics is tribal).

Since there is not a single uncontroversial way to identify or guarantee the undisputed “right” winner, I set a lower–but achievable!–bar of finding a system that guarantees it will not elect the “wrong” winner, which is easier to agree upon (though, VSE doesn’t necessarily agree that someone who a majority did not want would not win)

I think who runs and how they run are of the utmost importance to engaging people in productive elections, but VSE is completely silent on those important topics. Asking VSE to tell me how an electoral method will change who runs and how they run would be like checking my speedometer to see whether I need to pick up milk on the way home.

Let me put it another way: if there were a model that 1) incorporated recent developments in game theory and behavioral economics, 2) modeled behavior across repeated rounds, so it could make some predictions about how voters and candidates would actually respond to different electoral methods over time (this is what game theory models do), and 3) tested itself against real-world experience to see whether it was getting it right and making useful predictions about the methods for which there is no real-world experience (this is what climate models do), I would be totally interested!! But VSE doesn’t do any of that. The only thing it can tell me is one controversial definition of who the “right” winner and whether that person could win if voters vote in a few different simplistic patterns that are not at all informed by game theory or behavioral economics.

I hope that helps explain some of what I see as the shortcomings of VSE. Thanks again for fighting for a better democracy!

Clay Shentrup

Kristin,

There are numerous problems with your comments on Bayesian Regret aka VSE.

> 1) incorporated recent developments in game theory and behavioral economics

What specific developments are you talking about? Warren Smith and I (and others in our camp) have read and cited renown thinkers in this space, such as Kahneman and Tversky. Steve Brams, the NYU political science professor most notable for advocating Approval Voting, is a game theory expert and has written several books on the subject. If you have a specific game theoretical argument to make, we’d appreciate hearing it. But the reality is that the analysis here is chock-full of game theory. It is simply bizarre that you suggest otherwise.

> 2) modeled behavior across repeated rounds

Repeated rounds are useful for determining equilibrium behavior, such as what proportion of voters will be tactical vs. honest after a new voting system has been in place for a long time. But the particularly noteworthy feature of Warren Smith’s Bayesian Regret figures was that Score Voting beat out the alternatives _regardless_ of that proportion. So this actually is not a particularly useful thing to measure.

> 3) tested itself against real-world experience to see whether it was getting it right and making useful predictions about the methods for which there is no real-world experience (this is what climate models do)

As anyone with a basic understanding of social choice knows, this is impossible without a hedonimeter. This is why you can’t use real humans for these calculations.

http://scorevoting.net/WhyNoHumans.html

> The only thing it can tell me is one controversial definition of who the “right” winner and whether that person could win if voters vote in a few different simplistic patterns that are not at all informed by game theory or behavioral economics.

It’s actually no more controversial than the notion that 2+2=4. The underlying math behind “right winner” is unimpeachable.

http://scorevoting.net/UtilFoundns.html

JAMES WALSETH

After an intense immersion in electoral politics 10 years ago, I came out with a great interest in IRV and other concepts discussed here.

Imagine my happiness when I moved back to the NW and learned that Pierce County was implementing this! And then my crushing disappointment when I learned that, it appears, voters just can’t handle it. It’s too complicated for a populace that in larger part cannot manage to get registered and vote, as is. So I find these academic arguments somewhat…. academic.

I will say that would prefer a system that tends to empowers the ‘passionate few’, because that’s who I am. And it’s what this is based on “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

Kristin Eberhard

Hi James – I’m glad to hear about your enthusiasm for electoral change. I hope to do a case study of Pierce County later this year to see what lessons advocates need to learn, but, from what little I know so far, I don’t think it’s just too complicated for voters to handle. Which is good, because voters in Australia, Ireland, and 13 places across the US, and soon the entire state of Maine can handle it, so it would be concerning if Pierce county voters were just less capable.

As to empowering the “passionate few,” unfortunately, our country has a long history of thinking this sounds like a good idea, but it’s usually not the people Margaret Meade had in mind who end up getting the most say. The original passionate few were wealthy, white, protestant males. We’ve slowly expanded to admit others can have a say in our democracy, but the urge to narrow back down is still strong, for example, many feel that if you can’t be bothered to get the right ID and bring it to the polling place then you must not be sufficiently passionate to be allowed to vote.

I’m of the opinion that, for a democracy to work, everyone must have a voice.

Louis

Why not consider liquid democracy? Only being able to vote once every couple of years is still a substantial problem even if we end up with the lesser of evils.

Kristin Eberhard

I’m very interested in liquid democracy! Not sure how to go about implementing in a public setting in the United States, but hope I might look into it more in the future.

Sigh

“only one makes it safe for voters to express an opinion about multiple candidates. … Under Instant Runoff Voting, it is safe to rank a weak third-party candidate like Nader. If you rank him first and he is eliminated, your vote transfers to your next-ranked candidate who is still in the running.”

This is absolutely false. Please stop perpetuating this lie.

Under IRV, if Nader becomes popular enough to actually have a chance of winning, voting honestly for him can cause Gore to be eliminated first and Bush to win. It is NOT safe to vote honestly under IRV in competitive elections. It’s only safe to vote honestly when your favorite candidate is going to lose anyway.

“because this situation so rarely occurs”

It’s already happened in real elections!! Why continue to promote a system that’s been shown to NOT WORK in the real world??

Ornstein & Norman showed that IRV has non-monotonicity problems in 15% of 3-candidate elections, increasing as the number of candidates increases. “Three-way competitive races will exhibit unacceptably frequent monotonicity failures … In light of these results, those seeking to implement a fairer multi-candidate election system should be wary of adopting IRV.”

William WAUGH

What good is “one person, one vote” if the votes do not count with equal weight? I claim a civil right to a vote that counts as strongly as yours, and IRV does not respect this right, but all Score systems (including Approval and Score Runoff Voting) do. The proof for the Score systems is that for every vote that you can cast, I can cast a vote that undoes the effect of your vote. IRV advocates have not brought a proof of the same property for IRV.