More than 50 years ago, Rachel Carson’s 1962 environmental classic, Silent Spring, urged tighter regulation of pesticides. Among the pesticides she identified of particular concern were “organophosphates,” chemical cousins of nerve gas that are neurotoxic to insects and that have side effects on other animals, including humans. Many of them are still with us, but a major one, Chlorpyrifos, may soon be revoked for use on food crops—and the window for the public to weigh in is closing fast.

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposal to cancel all uses of the pesticide Chlorpyrifos on food crops was a long time coming.

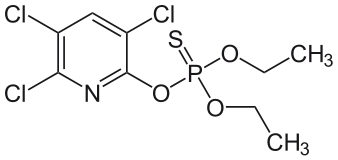

Chlorpyrifos by Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain.)

Chlorpyrifos was first used on crops in the US in 1965 (even three years after the publication of Silent Spring), and the chemical continues to be widely used on food, particularly in the Midwest. Yet according to its manufacturer, Dow Chemical Chlorpyrifos is also used in Western states on some of our trademark Northwest crops, including apples, pears, and cherries, as well as sugar beets, lentils, and wheat. In California, Chlorpyrifos is still applied to citrus fruits, wine grapes, tree nuts, and sweet corn. But perhaps for not much longer.

Chlopyrifos Use Map in the Western US by US Geological Service (Public Domain.)

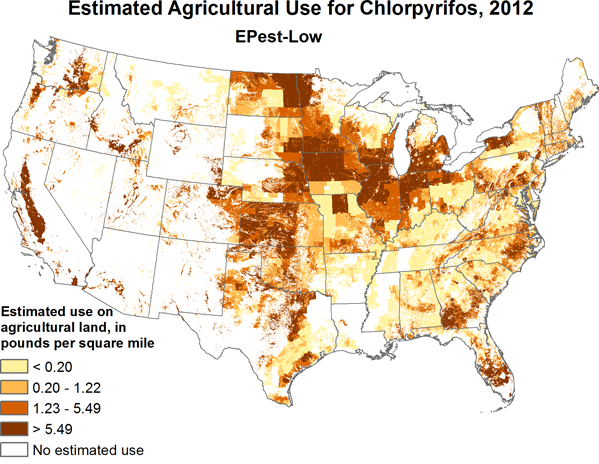

Chlopyrifos Use Map in the US by US Geological Service (Public Domain.)

In the 1980s and 1990s, Congress strengthened federal laws regulating pesticides, and accordingly, EPA has already implemented some controls on Chlorpyrifos.

In 2000, acknowledging the neurotoxic properties of the chemical, EPA reached an agreement with the chemical’s manufacturers to voluntarily restrict the use of Chlorpyrifos spray cans in places where children may be exposed, including homes, schools, and day care centers. The move effectively eliminated most of this chemical’s household uses.

Then in 2006, EPA took further steps. To reduce dietary risk, especially to children, the EPA revoked the use of Chlorpyrifos on tomatoes and reduced the applications on apples and grapes. Other restrictions were designed to reduce pesticide exposures to farm workers. At the same time, EPA confirmed that Chlorpyrifos remained “one of the most widely used organophosphate insecticides” and that American farmers were annually deploying over 6 million pounds of it on their crops.

In 2007, frustrated by EPA’s lack of progress, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Pesticide Action Network (PAN) filed a petition to ban all uses of Chlorpyrifos. The groups noted among their arguments that EPA failed to consider some pathways of pesticide exposure to the children of farmworkers, such as “spray drift,” from fields. They also argued that EPA had discounted recent scientific studies in peer-reviewed journals that linked pre- and post-natal Chlorpyrifos exposures to IQ and memory deficits in children and that researchers could identify no safe level of exposure in early life. They concluded by noting that adults and children would continue to be exposed to unsafe levels of Chlorpyrifos as long as the chemical was used on food crops.

In 2012, partly in response to the petition, EPA expanded Chlorpyrifos “no-spray buffers” to protect areas adjacent to agricultural fields. Such buffers reduce exposures from spray drift to bystanders, including workers, their family members, and others. Buffers around land and streams also protect wildlife, including fish and other aquatic life.

Yet by mid-2015 EPA still had not provided a final response to the PAN and NRDC petition, a failure to act that the groups argued placed them in “regulatory limbo.” The two groups sued, requesting that the US Court of Appeals order EPA to make a final decision or adhere to a timeline for making one.

The Appeals Court acknowledged “the scientific complexity inherent in evaluating the safety of pesticides and the competing interests that the agency must juggle;” but nonetheless found that the delays on Chlorpyrifos were “egregious.” The judges ordered EPA to respond to the petition by the end of October.

The US is now on the cusp of revoking all use of Chlorpyrifos on food crops. The public has one opportunity to weigh in: public comments on the proposal are due by January 5, 2016. They can be submitted via this link.

EPA’s proposal for the Chlorpyrifos revocation can be found here, along with a detailed summary of the scientific information.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material that Sightline staff members turn into articles.

rl

I was doing pest control in the 80s and early 90s. This pesticide was commonly used. I searched online and at conferences regarding its safety, and a friend who was an industrial hygienist searched. NOTHING raised any safety concerns. I now suspect that the industry may have been hiding information.

John Abbotts

Hello rl,

Thank you for your comment. Well, I have no evidence that the industry withheld information from EPA. But the industry certainly fights tooth and nail against any attempts to reduce their profits by regulation.

In fact, according to Wikipedia, when Rachel Carson began to investigate pesticides, and attended federal hearings in the 1950s, “she was discouraged by the aggressive tactics of the chemical industry representatives, which included expert testimony that was firmly contradicted by the bulk of the scientific literature she had been studying. She also wondered about the possible “financial inducements behind certain pesticide programs.” (link at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silent_Spring)

When NRDC and PAN filed their petition in 2007, they based much of their arguments on studies published in scientific journals by independent researchers. (Our article contains an embedded link to the petition, which I repeat here: http://docs.nrdc.org/health/files/hea_10072201a.pdf )

This underscores the value of providing federal funds for university research by scientists unbiased by financial temptations. In addition to the situation with pesticides, it was not the automobile industry that warned of the dangers of smog, nor the tobacco industry that warned of the dangers of smoking. Much of the research that raised alarms was conducted by independent scientists. And then there is always climate change, where the evidence now is that Exxon was aware by the 1980s of the potential for climate change, but only looked for ways to delay regulations and continue profiting. (link at http://grist.org/climate-energy/exxon-has-known-about-climate-change-since-the-70s-and-is-still-trying-to-block-climate-action/)