It’s tempting to blame politicians. If only Obama were warmer, he might be able to win over Republicans. If only Doug Ericksen weren’t captured by fossil fuel money, he would find a way for Washington state to take action on climate change.

But gridlock is now the norm in Washington, DC, and it may be spreading to state legislatures. The problem is not that we keep electing representatives who stink at compromising. Rather, our voting system fosters gridlock. The apples (politicians) are fine when they go in; the barrel itself (winner-take-all voting) makes them rot.

I have explained that winner-take-all voting creates unrepresentative government that gives short shrift to women, racial minorities, and third-parties, while also encouraging negative campaigns and voter apathy. Proportional representation voting elects women, racial minorities, and political minorities in numbers proportional to their strength in the populace, and it generates civil campaigns and engaged voters. In this article, I show that winner-take-all voting produces gridlocked legislatures, but multi-winner ranked-choice voting creates more effective legislatures.

Problem: Legislatures are partisan, polarized, and gridlocked

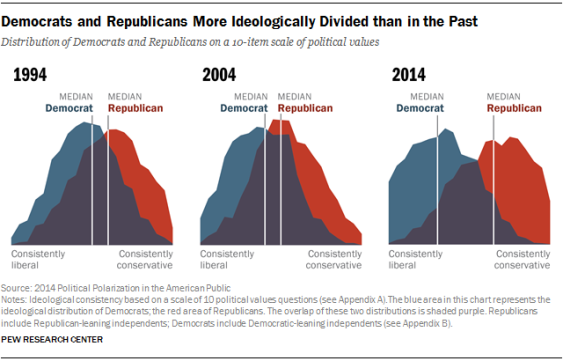

In the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties are pulling away from each other ideologically. In 10 years, Democrats have moved seven points to the left, and Republicans have moved 22 points to the right. They are leaving a chasm in the middle. Only four percent of the members of the US House are moderate. Only six percent are crossover representatives: Republicans in a Democratic-leaning district or vice versa.

Democrats and Republicans More ideologically Divided than in the Past by Pew Research Center, Washington DC (June, 2014) (license) (Used with permission.)

Not only have the parties moved apart, but party members increasingly see the opposing party as a “threat to the nation’s well-being.” Such venomous distrust is a recipe for gridlock.

Beyond Dislike: Viewing the Other Party as a ‘Threat to the Nation’s Well-Being’ by Pew Research Center, Washington DC (June, 2014) (license) (Used with permission.)

Intensifying partisanship has several causes in the United States.

1. The two parties have sorted themselves along ideological lines.

In previous eras, the two parties were ideologically mixed: some southern conservatives were Democrats (“Dixiecrats”) while some liberal Northerners were Republicans. Mixed parties could form bipartisan coalitions. But the parties have straightened themselves out. Modern, ideologically consistent parties have little opportunity to reach across the aisle.

Polarized House, 1879 to 2014 by VoteView (Used with permission.)

2. Voters are sorting themselves geographically, creating safe districts for the two parties.

Democrats want to live in dense, walkable, cultural centers. Republicans want to live in big houses with stores and restaurants driving distance away. As fivethirtyeight.com statistician Nate Silver summed up: “if a place has sidewalks, it votes Democratic. Otherwise, it votes Republican.” This self-sorting has inflated the number of safe districts in the United States—districts where one party has a nearly unbeatable advantage. In 2014, nearly two-thirds of US congressional districts were safe for one party.

Contrary to popular belief, Machiavellian partisan gerrymandering is not the main cause of safe districts. Washington’s bipartisan redistricting commissions create nearly as many safe districts as does gerrymandering. In 2014, 100 percent of US Congressional districts in Washington were fairly safe, and 60 percent were very safe. Self-sorting creates increasingly monolithic forts of liberal urban legislators and rural conservative legislators with no one able to cross between.

3. Party primaries empower the most extreme and partisan voters.

Because most Congressional districts are safe for one party or the other, that party’s primary becomes the real election. Primary voters are more partisan and more conservative than the general electorate. (GOP primary voters are also much older and whiter.) By the time the general public votes, the race has already been won, often by a candidate who is more extreme than the general electorate would have preferred. Because turnout is often half as high in primaries as in general elections, and because one party usually has a lock on the general election, a tiny percentage of highly partisan primary voters is effectively electing the candidate.

In 2014 , some 71 percent of Oregon voters cast general election ballots, but only 36 percent voted in the primary. Because almost every district is safe for one party, that party’s primary voters effectively selected the winner. For example, Oregon’s state House District 2—

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

covering parts of Douglas, Jackson and Josephine Counties—is a safe Republican seat. In the 2014 primary election, Dallas Heard won 4,708 votes and went on to win the general election against a Democrat by a landslide. Because the Republican candidate is all but guaranteed to win that district in a general election against a Democrat, Heard’s primary voters—less than 15 percent of registered voters and about 10 percent of the district’s voting age population—effectively elected him.

Even Washington’s top-two primary has not solved the problem of primaries as arbiter of partisanship: voter participation in primaries is low (albeit higher than the national average), and the “top-two” almost always are a Democrat and a Republican. In only 1 out of 56 elections has the top-two primary advanced two Republicans. So even with a top-two system, partisan primary voters are selecting two representatives from the two major parties, often handing the win to the candidate from the dominant party in a safe district.

4. Scorched earth, not compromise, builds party power.

In a parliamentary system, like that in British Columbia, one party (or coalition) can actually govern: it has the responsibility and the power to enact an agenda. At the next election, voters can decide whether they liked that agenda or not. Partisanship doesn’t lead to gridlock; rather, it leads to starkly defined choices.

The United States’ system of government is not parliamentary: it’s a presidential democracy, with separately elected executive and legislative branches. This system worked well enough at fostering compromise when the two parties were fluid and included a diversity of views. At times, the United States has functioned effectively like a parliamentary system because the same party won control of the presidency, the Senate, and the House, empowering that party to enact its agenda. For example, the super-majority Democratic 89th Congress under President Johnson was very productive.

But two rigid parties splitting control of the presidency and Congress leads to gridlock. Most Americans believe the president is in charge of the country’s direction and expect him to deliver results, just like in a parliamentary system. In the 1990s, Newt Gingrich successfully exploited this quirk of our system: Republicans embarked on a strategy of blocking the Democratic president at all costs. Voters blamed the inaction on the President and instead voted for Republicans. Deliberately bringing the federal government to a standstill works: the base turns out to vote, and plutocrats open their wallets to fund the partisan battle. Compromise is a fool’s errand. Obstructionism wins.

5. Legislators must hew to the party line.

In a strong two-party system, candidates have little chance of getting elected if they run outside the established two parties. The major parties help select, groom, and fund most successful candidates. Once elected, the candidates are beholden to the party establishments, and individual legislators often toe the party line, as demonstrated in record numbers of party-line votes. This dynamic dampens honest legislative discussion in favor of straight partisanship.

Solution: Defuse partisanship by electing more crossover representatives, more independents, and third-party representatives, and by creating incentives for bridge-building.

Multi-winner ranked-choice voting elects a greater diversity of representatives, defusing the power of partisanship. Just ask Illinois legislators. They can testify, from experience, that a legislature elected by multi-winner voting is more concerned about representing all viewpoints than about playing party politics. From 1870 to 1980, Illinois used multi-winner voting to elect members of the Illinois House of Representatives. In 1980, Illinois reduced the size of the house to save money, and as part of that “cutback,” it changed to single-winner districts. (A bipartisan task force has since unequivocally recommended that Illinois return to a multi-winner system to “provide greater representation to the minority political party in districts dominated by one party” and create “richer deliberations and statewide consensus.”)

1. Ideologically diverse representatives emphasize ideas, not partisanship.

Greater diversity of voices lessens the power of party politics because discussions no longer split along party lines. Jeff Ladd, former Illinois constitutional convention delegate, said that multi-winner districts reduced partisanship in the Illinois House. “It resulted in a much less partisan legislative body, one that was much more open to dealing with members on the other side based on the strength of ideas, rather than the party relationship. I think that’s absent today [with the switch to single-winner districts]. Almost everything is a partisan vote.”

John Porter, an Illinois Republican who served in both the state house and US Congress, agreed that Illinois’ multi-winner districts “led to a much more independent and cooperative body that was not divided along party lines… it allowed individual legislators to pursue the ideas that they had for improving government apart from party considerations and to work with members on both sides of the aisle.”

Independents are the largest block of voters in Washington, and independent, unaffiliated, or third-party members together make up a bigger group than Republican voters in Oregon. Yet every single one of the 256 elected representatives in the two states’ federal Congressional delegations (Oregon, Washington), state houses (Oregon, Washington) and state senates (Oregon, Washington), is either a Democrat or a Republican. Oregon and Washington voters would certainly elect more independent and third-party representatives, creating more effective and less partisan legislatures, if the voting system gave them a chance.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

2. Crossover representatives elevate voters’ interests above party interests.

Winner-take-all elections leave urban conservatives and rural liberals with no representation in the legislature. For example, Republicans in Oregon’s Congressional District 3 (east Portland, Gresham, and Troutdale) haven’t had a representative in Congress since 1955. Liberals in eastern Oregon have only elected two Democrats in the history of the state and none since 1981. No one in the Democratic caucus talks about suburban or rural issues, and no one in the Republican caucus represents urban issues, so the parties never have to talk about the diversity of voters they supposedly represent.

Multi-winner elections would enable conservative urbanites and liberal rural-dwellers to elect representatives reflecting their views, creating a richer and more accurate discussion about all voters’ needs. Dawn Clark Netsch, former Illinois state senator explained how this worked in the multi-winner Illinois House: “[W]hen the Republicans went into their caucus in the House, there were a couple of people who were from Chicago. That was very important. I think by the same token it was important to have suburbanites… in the Democratic caucus who could say ‘Hey wait a minute, you guys from Chicago, you don’t own the whole world, people are going to the suburbs and here’s something you ought to be taking into account.'”

3. Multi-winner districts thwart the partisan power of gerrymandering.

Multi-winner districts provide a durable solution to gerrymandering and safe districts. Because voters have self-sorted, even bipartisan commissions will create safe party districts. It’s not the districting commission’s fault; it’s the winner-take-all system—the dominant party in the district gets to elect a representative, and the minority gets no representative. But in a multi-winner district, most voters will cast at least one vote for someone who wins. No matter who draws the lines and how they draw them, most votes will count.

4. Constructive compromise—not extremist obstructionism—becomes a winning strategy.

Multi-winner voting enables candidates to run a successful campaign with less money, diminishing the importance of the major parties in selecting and financing candidates. As former Illinois state senator Arthur Berman explained: “Today you see the very, very powerful role that the legislative leaders play in raising money and diverting that money to candidates that they want to support. Back under [multi-winner] voting, the power of the leadership wasn’t what it is today because candidates for the House only needed one-quarter of the vote. They could concentrate on the people they wanted to have vote for them, and they didn’t have to go and get Big Money from the leadership. They could do it primarily through their own resources.”

Because proportional representation allows more variety within party representatives, and also would elect more independent and third-party representatives, the incentive for the minority party to obstruct the majority party would be lessened. If the majority party could craft solutions that attract enough independents, third-party voters, or moderate members of the smaller party, it could move forward with its agenda and leave the extremists in the dust. Extremists could no longer derail action by refusing to come to the table. They just wouldn’t be at the table.

Indeed, other countries—such as Germany and New Zealand—that use proportional representation do not experience partisan gridlock.

A Better Barrel

Many Oregonians and Washingtonians yearn for a better political process, sometimes wishing candidates could just be kinder to each other, or that the parties could just compromise instead of gridlocking, or that independent commissions could re-draw district boundaries to avoid gerrymandering.

But as long as deep partisanship defines elections and party primaries elect extreme partisans, the parties will have to play to their bases. As long as self-sorted safe districts elect just one partisan representative and render other voices within the district mute, we couldn’t overcome partisanship even if we got Mother Theresa to draw the district boundaries. As long as winner-take-all voting creates two strong, ideologically distinct parties, neither of which has the power or responsibility to enact an agenda, the party that is not in control of the executive branch will benefit more from unadulterated obstructionism than from constructive compromise.

Multi-winner ranked choice voting can defuse partisan gridlock by electing a more diverse and representative legislature that can find common ground and move forward.

Thanks to FairVote for its research on proportional representation and ranked-choice voting. This article relies heavily on it.

John Gear

Again you are on fire. It is so, so deeply refreshing to see people move out of their single-focus silos and start to explore the root causes of the problems. Well done, keep it up!

I love your metaphor of the barrel turning the apples bad — everyone has seen great people run for office and win and become unrecognizable in no time flat. That makes some people cynical, but the wiser choice is to do as you are doing and examine what is going on to turn these people against what they believed as candidates. The way we stock our “barrel” guarantees that the worst traits in the apples are reinforced and that none of the apples can escape being saturated with the most toxic strains. Luckily, there are better ways, as you are sharing.

Stoney Bird

Thanks for these wonderful articles. I’ve been writing about proportional representation in Whatcom Watch (www.whatcomwatch.org) since last summer, and have been talking with the Whatcom Charter Review Commission since it began meeting in January. PR will actually be on the Commission’s agenda this coming Monday. 🙂 What they decide to do with it is another question.

J. Data Logan

Great job, Kristin, on these recent articles delving into the many issues with winner-take-all elections and the benefits of ranked choice voting and multi-winner voting.

I continue to believe that this root issue is the most important one in (American) politics. It’s nice to see someone else getting the message out–and in much more eligant ways that I could.

Still, I’m still looking for the next step. Now that we have identified the root issue that needs to be worked, just how do we go about fixing it. I have had no real luck finding people or groups actively working on these kinds of election reforms in the Cascadia area. If I could I would certainly want to give them my support, as I have offered Sightline.

In the meantime I am doing want (limited amount) that I can just as a single citizen: meeting with election and legislative officials at county, district, and state levels. (My next meeting is 6 July with state election officials in Olympia.) But there’s only so much I can do as a single concern citizen against the road-block of our existing system.

Please let me know if you are aware of any groups actively working these issues.

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks, J. Data. I plan to turn next to how multi-winner and/or ranked choice voting have worked in North American cities, states and provinces, and then tackle what it would take to start moving in this direction in the Pacific Northwest. Hopefully this next round of research will turn up those who are working on it, and illuminate paths towards change.

Joe Cobb

We support RCV in Arizona because we are numerically small but those numbers are never effectively counted. The Arizona Libertarian Party expects our candidates would receive a significant share of the 1st Choice ballots if a 2nd Choice were more popular in the polls. To be a visible minority is better than being an invisible minority, since “strategic voting” and negative voting dominates the winner-takes-all system.

We linked your article on our facebook page.

Kristin Eberhard

Thanks!