Grab the issue you care most about—climate change, sustainable cities, a fair economy, or something else—sit it down, look it in the eye, and tell it there will be no Christmas this year. Or next year, or the next—we cannot fix important problems until we fix democracy.

[prettyquote align=right]”Remove #corruption from elections, and #democracy will become responsive to citizens.”[/prettyquote]

Climate change should be imminently solvable. We know which policies work. We have clean technologies, and people want to fix it. But none of that matters if government doesn’t represent the people. If government is implementing policies and propping up industries because they are lucrative for a small group of plutocrats, then no amount of public demand or technology solutions will help us solve climate change. Or any other issue that we care about.

We need a government that represents the people.

Professor Larry Lessig eloquently explains that the root of the problem, the fundamental corruption of US democracy, is elected officials’ dependence on the tiny number of wealthy funders who control elections. Remove corruption from elections, and democracy will become responsive to citizens.

But there is more than one root.

Lessig raised an $11 million PAC to elect anti-corruption candidates to the US Congress in hopes of getting enough votes to pass a nation-wide Anti-Corruption Act. The support of 95 percent of Americans plus a big chunk of money should win a few elections, right? Wrong. Lessig’s first effort flopped, yielding an important lesson: in a two-party system, partisanship trumps everything. Even dearly held issues. Even money.

You can prove the primacy of partisanship to yourself right now: say you are a Democrat. In the next Congressional election, you have to choose between voting for a Democrat who has not come out in favor of campaign finance reform, or for an anti-corruption Republican (yes, this hypothetical is less likely than the reverse situation—ten out of 300 Republican Congress members are anti-corruption, compared to 138 out of 236 Democrats). You care deeply about campaign-finance reform. You know we can’t solve anything else until we solve it. Do you vote for your only anti-corruption option, the Republican? No! That guy could tip the majority to a party that is going to limit women’s reproductive health, legalize concealed guns, and abolish the estate tax. Hell no. You vote for the Democrat. And elect one more member of Congress who is not going to pass a bill to oust corruption. Sigh.

In a two-party system, partisanship trumps all.

The outsized influence of money is a root problem, but there is another root: the structures of democratic representation in North America disenfranchise voters. I already explained the horrors of the Electoral College and how we can help make it irrelevant. Gerrymandered, single-member, winner-take-all districts are worse. They elevate fundraising above all other political skills, entrench a bitterly partisan two-party system in the United States, and, in Canada, enable rule by factions that often do not command a majority of public support and force voters to cast votes tactically, because real representation is unattainable.

[prettyquote align=right]”Allowing voters to break free of partisanship and elect candidates who more accurately reflect their views would result in a Congress that looks a lot more like the people.”[/prettyquote]

Picture that Congressional election again, but this time imagine that instead of being forced to choose either the Democrat or the Republican, you could elect three out of six possible candidates. You rank six possible candidates for Congress, and the top three vote-getters will win a seat. Your choices: a typical Democrat, a typical Republican, a Warren-wing Democrat, a Tea-Party Republican, a Green Party member, and a Libertarian. Let’s say every candidate other than the typical Democrat and Republican are anti-corruption.

What do you do? You rank the Warren-wing Democrat first because we need more Elizabeth Warrens in office. You rank the Libertarian second because he is committed to making the tax system simpler and fairer, and your third ranking goes to the Green Party member because she will fight for social justice and sustainability. If your top three choices win, you elected three anti-corruption members of Congress instead of none (in the two-party scenario).

If you are in a “safe” Republican district, then under a two-party system you have no shot at electing a candidate, but in this “elect three” election you are guaranteed to put at least one candidate you support in office. Isn’t that satisfying? Conversely, if you’re a conservative in urban Cascadia, your vote will never count in a two-party system, but you and your fellow urban conservatives would have a voice in an “elect three” system. In Canada, instead of choosing to throw your vote away on the Greens, or sacrificially vote for the Liberals, you could vote your true preference and know that everyone’s preference will be reflected in Ottawa.

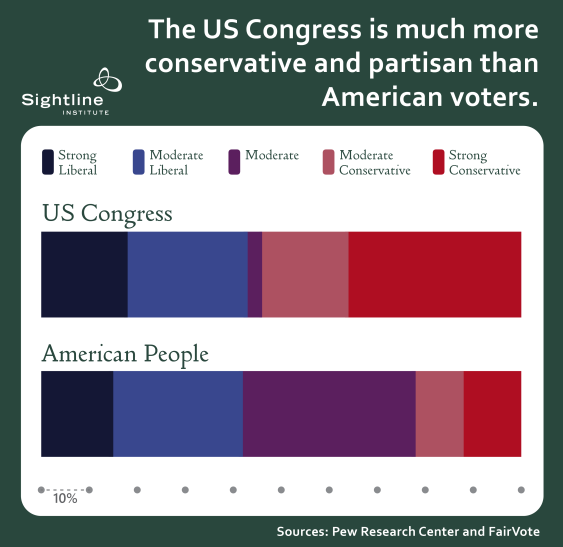

Now imagine the US Congress that would emerge from such an election. In the current gerrymandered, two-party system, Congress is much more conservative and partisan than the American people it is supposed to represent. Look at that large swath of unrepresentative red swallowing up the purple in the current Congress: that’s what “no Christmas” looks like. Allowing voters to break free of partisanship and elect candidates who more accurately reflect their views would result in a Congress that looks a lot more like the people. Look at the big purple middle of the American People and the small minority of Americans who hold uniformly conservative values: that’s what potential for progress looks like.

Maybe you are thinking this sounds like a nice pipe dream. Sure, we could use multi-member districts and ranked-choice voting and elect a legislature that actually represents the people—hah, yeah, or maybe we could all sprout wings and fly through the halls of power in our capitols and sprinkle magic fairy dust that makes sustainable policies pass.

[prettyquote align=right]”It won’t be easy. But nothing this important is. And it will be worth the fight because a functioning representative democracy is a prerequisite to a sustainable Pacific Northwest.”[/prettyquote]

It’s not a pipe dream. It’s a realistic dream. Alan has been describing the ways to get a grip on money in politics and reform the initiative process. He’s even helping to launch a first-ever democracy voucher program in the city of Seattle, as a proving ground for broader reform. I’ve described how to dramatically expand voting. With this article, I launch a new series of articles that unveil how we northwesterners can have representative democracy. It’s within our grasp. We don’t need a Constitutional Amendment. We don’t need a revolution. We just need to increase the use of voting methods that many American states, Canadian provinces, and cities are already using or have used in the past. Experience with these voting methods shows that a few modest changes mean the difference between bitter partisan campaigns plus a gridlocked legislature, and constructive campaigns plus a representative democracy.

It won’t be easy. But nothing this important is. And it will be worth the fight because a functioning representative democracy is a prerequisite to a sustainable Pacific Northwest.

There will be no Christmas until we succeed, but once we do, every election will feel like Christmas as Santa finally delivers the government we asked for.

Note: In the chart, for the classification of Congress, I used FairVote’s analysis. For the classification of the American People, I used Pew Research Center’s 12 Political Typologies and broke them down as follows: Strong liberal includes Pew’s Solid Liberal; Moderate Liberal includes Pew’s Faith & Family Left and Next Generation Left; Moderate includes Pew’s Hard-pressed Skeptics, Young Outsiders, and Bystanders; Moderate Conservative includes Pew’s Business Conservative; Strong Conservative includes Pew’s Steadfast Conservative.

Comments are closed.