Thomas Jefferson believed that “[e]very constitution… naturally expires at the end of 19 years.” As “new discoveries are made, new truths disclosed… institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times.” But Jefferson did not manage to insert a 20 year reset button into the US Constitution; instead, the nation ended up with the most difficult to amend or update Constitution in the entire world. The United States is number one!

The US Electoral College is a poster child for Jefferson’s fear that a constitution may linger beyond its natural life. When the Founding Fathers conceived of the Electoral College as “a small number” of “men most capable of analyzing” the “complicated” question of who should be president, there were fewer eligible voters in the whole country than there are now in just the city of Portland (there were only 2.5 million people in the whole country, and only a tiny fraction of those—white, wealthy, Protestant men—were allowed to vote). The Electoral College has always been a rubber stamp rather than the deliberative body the Founding Fathers imagined.

[prettyquote align = “left”]”The United States is the only country in the world still inserting an Electoral College between voters and the presidency.”[/prettyquote]

While the United States has tried to bring the Constitution out of the 18th century by amending it to allow men who aren’t white to vote (14th Amendment, 1870), to allow women to vote (19th Amendment, 1920), and to let voters elect their own Senators (17th Amendment, 1913), the country has not been able to escape from the dead grip of the Electoral College. The United States is the only country in the world still inserting an Electoral College between voters and the presidency. This creaking anachronistic scheme anoints the less-popular candidate president one time in seven (ignoring landslide elections). A candidate could win just 22 percent of the popular vote and win the presidency, and a candidate has won the presidency with just 31 percent of the vote. The Electoral College lingers because small states and swing states that loom larger than life in the Electoral College system can easily block Constitutional amendments.

Luckily, amending the Constitution is not the only path to change. The Constitution lets states decide for themselves how to assign their Electoral votes. The National Popular Vote Compact, already passed in Washington and now pending in the Oregon legislature, would use the power of the Constitution to modernize US presidential elections. Over the past 200 years, states have experimented with different ways to exercise their Electoral College powers. At present, most states award their Electoral votes on a “winner-take-all” basis: the presidential candidate who gets the most votes in the state gets 100 percent of the state Electors’ votes. This system results in a host of ills for the country:

- Counterintuitively, the candidate who gets the most votes does not necessarily win the presidency. In 2000, the state winner-take-all system chose George W. Bush, despite Al Gore’s half-million vote lead in the popular vote. But the mismatch between people’s votes and Electors’ votes may not always favor the Democrat. There have been six other near-miss elections since World War II, including in 2004 when a shift of just 59,393 votes in Ohio could have awarded the presidency to John Kerry, even though George W. Bush would still have won the popular election by nearly 3 million votes.[prettyquote align = “right”]”Presidential candidates ignore four-fifths of Americans and spend all their time and money campaigning in just a few battleground states.”[/prettyquote]

- Presidential candidates ignore four-fifths of Americans and spend all their time and money campaigning in just a few battleground states. In 2012, presidential and vice presidential candidates only held post-convention public campaign events in 12 states, including 73 visits to Ohio alone. They spent $463 million on TV ads in just 10 states. Candidates held exactly zero public campaign events in the Pacific Northwest and spent almost no money advertising in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Sure, they were happy to do quick stops in Cascadia to collect checks from large donors, including $10.5 million from Oregon donors; but they left without holding any public events or listening to voters’ concerns, and they whisked the money off to enrich the economies of other states.

- Favoritism towards battleground states doesn’t stop after the votes are counted. By the time they are elected, presidents and their staff members have spent a lot of time listening to and thinking about the issues important to people in battleground states, but no time on the issues important to people in “spectator” states, including Oregon. They continue to have an interest in wooing battleground states, either for themselves or for the next candidate from their party. Not surprisingly, the few battleground states receive more federal funds than the many spectator states, more grant dollars, twice as many presidential disaster declarations, more Superfund enforcement exemptions, and more No Child Left Behind exemptions.

- Voters in spectator states correctly sense that their votes for president do not matter. Voter turnout in battleground states is about 11 percent higher than in less competitive states. Voter turnout often trends upward as a state gets more campaign attention, and downward if a state gets none. Oregon has worked to be a leader in voter turnout, but being ignored by presidential campaigns doesn’t do any favors for Beaver State voter motivation.

But states have the power to release themselves from this peculiar historical bondage.

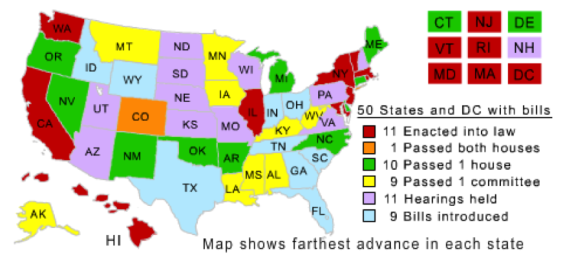

Ten states plus the District of Columbia have signed an interstate compact agreeing to award all their Electoral College votes to the presidential candidate who wins not the election within their own borders but instead the national popular vote. If enough states sign on to elect the most popular president, the compact will take effect. These states will then send their Electoral College representatives with instructions to cast ballots for the national vote winner, and the US presidential campaign will suddenly be a national one, not a swing state affair. So far, the compact has 165 electoral votes—61 percent of the 270 electoral votes necessary to activate it.

Seventy-six percent of Oregonians and 77 percent of Washingtonians want to change the current system and elect the presidential candidate who gets the most votes. In 2009, Washington legislators affirmed the will of the people and enacted a bill signing Washington on to the interstate compact for a national popular vote. Similar Oregon bills passed the House in 2009 by a 39-12 margin and again in 2013 by a 38-21 margin. They never made it out of the Oregon Senate partly because Senate President Peter Courtney opposes a popular vote. But Oregon is trying again, with 16 representatives sponsoring HB 3475 and 13 Senators sponsoring SB 680. If Oregon succeeds this time, it will bring the compact to 65 percent of the way to electing the most popular president.

Oregon’s efforts have some bipartisan support—five out of 29 sponsors are Republicans. At a hearing this month, the head of Oregon College Republicans joined Common Cause, The Bus Project, and League of Women Voters in urging Oregon legislators to pass a bill. The College Republicans leader told legislators that young Republicans want their votes to count, and under the current winner-take-all allocation of Electoral votes, they don’t.[prettyquote align = “right”]”#OR has the power to improve the way presidential elections work.”[/prettyquote]

Interestingly, despite strong national and bipartisan support for the idea of electing the most popular president, so far only “blue” states have joined the compact. The 24 bluest states, including 8 purple states, could join together to enact the compact. But spectator red states whose interests are ignored have more to gain than purple states. In red Oklahoma, a bill passed the Senate last year by 28-18 and this year the House is trying again. The Arkansas House passed a bill in 2009 and the North Carolina Senate passed one in 2007. If a bill passed in each of the 11 states where one has already passed at least one house, and in four of the nine states where one has already passed at least one committee, the compact would take effect.

The Founding Fathers may not have installed the Constitutional reset button that Jefferson wanted, but they did give states the power to improve the way presidential elections works. Oregon could be part of that proud tradition.

Comments are closed.