Editor’s Note 5/3/16: Does the record-warm spring have you craving to hop back on your bike… but still a bit nervous to navigate busy city streets? In this popular article, former Sightliner Jennifer Langston shows how you can get around on neighborhood greenways, a network of family-friendly roads. Read (and ride) on!

I haven’t used a bike to get across town in six years. I know because that’s how long it’s been since I had a baby.

It wasn’t entirely the baby’s fault—options and resources for family biking in the Northwest have exploded. But having less time, a rotting garage door (now fixed!) and an inconvenient daycare in automobile-choked Amazonia were barriers to using my bike more often.

I’m somewhere on the spectrum between the “enthused and confident” and “interested but concerned” bike user that so many cities are trying to win over. During the pre-baby year I spent in Cambridge, Mass., my bike was a main mode of transportation. Since then, I’ve bought a used Burley trailer, biked recreationally, and occasionally hauled my kid a few blocks to the grocery store or playground. But I assumed Seattle’s bike infrastructure was too unintuitive and stressful to meet my needs for getting around. From my pre-baby days, I recalled bike lanes to nowhere, frequently having to pull over to check a map, not being sure I was in the right place, thinking sharrows were a mean joke, and being thankful if you had a white stripe that separated you from oblivious drivers in cars that were moving pretty fast.

So I was genuinely surprised last week when I discovered it was relatively easy to take a mapless bike ride from my house near Woodland Park to I-5 to Puget Sound, with only a vague goal of testing the two neighborhood greenways in my neck of the woods.

Children give you an easy benchmark by which to measure how much things change. And I can unequivocally say that in the last six years, Seattle’s bike infrastructure has gotten noticeably better for someone like me. In this post, I’m going to focus on neighborhood greenways—a tool that Portland has used widely (which I’ll discuss in a future post) and that Seattle is now banking on to attract left-out bikers, create a family-friendly network of calmer streets, and make the city safer for people of all ages and abilities.

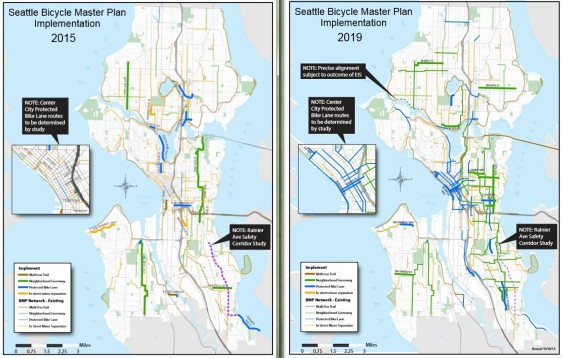

Seattle is planning to build lots of them—52 miles in the next five years (presuming that voters renew some version of the Bridging the Gap levy that mostly funds them) and 250 miles in all. They’re the green lines on the two maps below.

To be sure, neighborhood greenways are just one part of what needs to be a much more complete network of streets that put people on a more equal footing with cars. We still have streets that are abominably unsafe for kids, and plenty of the problems that I outlined above. But I now realize we are making slow progress towards a city where I might feel less skittish about letting my young daughter develop her own sense of independence and wonder on a bike.

For instance, there happens to be a new bike lane and road diet on Green Lake Way, which provided a missing chunk of connectivity in my neighborhood. On my recent ride, that led me to discover there’s also a short bike lane (hidden under leaves) on N. 50th Street as it passes the zoo, thereby answering my longstanding question about the best way to get from my house to the other side of Hwy 99.

Wayfinding signs led me off Phinney Ridge and down via a twisty route that I probably never would have discovered on my own. But it was very well-marked, with a sign at every turn. This makes a huge difference to casual or spontaneous cyclists who want some confidence that they’re generally headed in the right direction but don’t necessarily like consulting maps or researching the best routes ahead of time.

The signs guided me to the new(ish) 2-mile Ballard greenway along NW 58th Street. There wasn’t an earthshattering difference between it and other residential streets. But there were enough small changes to make me feel like the person who designed the street clearly thought about my needs as a person on a bike, valued them, and was doing something to lessen the chances that I would wind up on the wrong end of a crash with a distracted driver. I was surprised by how it made me feel: better, safer, in-the-know, and also a little bit empowered, like I actually had some rights in the world.

What is a neighborhood greenway?

In its ideal form, a neighborhood greenway is a residential street that’s designed for pedestrians, cyclists, and local vehicle traffic. It’s not for cars whizzing by on their way somewhere else and using neighborhood streets to avoid main roads. Greenways use a variety of traffic calming measures to discourage cut-through vehicle traffic, as well as signage and signal improvements to help cyclists and pedestrians get across the busy intersections safely.

When a city gets a critical mass of neighborhood greenways, they begin to form a usable network of streets that are more safe and comfortable for bikers, kids, parents, wayward pets, senior citizens—basically anyone who isn’t moving at 30 miles an hour. Sharrows painted along the greenways are primarily used as wayfinding tools to show people where to go and how routes connect, not as ineffectual warnings on high-traffic streets that a bicycle might be trying to share the road.

To be honest, I didn’t actually get what greenways were supposed to be until I saw this video from Portland:

That’s largely because Seattle built its first greenway—along N 43rd and N 44th streets—in my neighborhood. When I checked it out after it was built, it was distinctly underwhelming—definitely not worth traveling eight blocks out of my way to ride on it.

There are some sad little sharrows painted on the road and the occasional sign confirming that you are indeed on a neighborhood greenway, but that’s about it. The mile-long greenway actually connects to bike lanes on Latona and Stone Way, but there’s no obvious signage at either end to tell you that.

Most of the smaller intersections have traffic circles with no stop signs (which this study from Vancouver BC found was actually one of the more dangerous intersection types for cyclists.) And there’s not much to help cyclists or pedestrians get across the busier intersections, except some road paint, yellow signs, and a median island of questionable utility.

In fact, when I biked it last week, it looked suspiciously like a car had run over the small island in the Stone Way intersection designed to give bikers and pedestrians a “safe” spot to rest. Here’s the guy fixing a flattened crosswalk sign:

Since that first unfortunate example, though, SDOT has begun designing better greenways, based largely on the model that Portland developed. That’s largely due to the effective advocacy of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways groups, who have begun identifying and lobbying for neighborhood-specific safety improvements that will create a network of family-friendly infrastructure across the city.

One key difference on the newer Ballard greenway is that stop signs have been flipped or installed at every minor intersection—even when there’s a traffic circle—so that people walking or biking along NW 58th Street have the clear right of way.

This makes intersections safer by forcing the cars traveling north or south to stop and look before crossing the greenway. It also makes the route a more efficient thru-way for bikers because they don’t have to slow down (quite as much) to check for oncoming cars at every block. The downside is that can also make the greenway a more efficient route for cars traveling east or west, which is why it’s important for cities to aggressively calm and divert vehicle traffic from neighborhood greenways. As Portland has learned from one of its early experiments, a greenway with a lot of through traffic is unsafe and unattractive to everyone else.

For greenways to feel comfortable to wary bikers, kids tossing a football, or neighbors chatting in the street, Portland has determined they should carry no more than 1000 cars a day, and ideally less than 500. And the people who do drive on them—residents, carpools, visiting friends, garbage trucks, postal workers, delivery drivers—need to travel at a slower speeds that are appropriate for a residential street with lots of foot-powered activity.

The NW 58th Street greenway uses speed humps to slow cars through some neighborhood stretches. And the major intersection with 15th Avenue NW includes this traffic diverter that forces eastbound cars to turn right or left off the greenway:

Side note: If aesthetics are important and money is no object, traffic diverters can be way more charming. Like this one from Vancouver BC:

Greenways also include improvements to help pedestrians and cyclists get across busy intersections. This often represents the biggest chunk of a greenway’s price tag, since traffic signals are more expensive than speed humps, paint, or signage. On the Ballard greenway they include a traffic light at 8th Avenue NW that pedestrians can activate to stop cars (though a less experienced biker like myself or someone hauling cargo or a kid probably has to dismount and walk over to the sidewalk to do it).

This intersection treatment at 15th Avenue NW is more convenient for bikers because this nifty bike button lets you turn the traffic light from red to green without getting off your bike.

At the intersection of 24th Avenue NW, there’s a flashing crosswalk sign that pedestrians and cyclists can trigger. Based on my experience, it’s not super effective at stopping cars right away, but it does get drivers’ attention quicker than a crosswalk sign alone.

Once I got near the end of the greenway, I followed the sharrows up 32nd Avenue NW (which I still probably wouldn’t love doing at rush hour) and headed home via N 77th street where the hill up Phinney Ridge is more manageable. It’s mostly an “umarked, unsigned connector” on Seattle’s bike map, and it isn’t radically different than a neighborhood greenway. But I did miss the stop signs—one driver speeding around a traffic circle clearly didn’t see me in time to slow down. And more wayfinding help would have been nice, since I was mapless and couldn’t quite remember which cross street in the 70s I was aiming to be on.

The pros and cons of greenways

Neighborhood greenways don’t just benefit bikers. They help pedestrians—particularly the elderly, disabled, toddlers, or anyone else who needs a little more protection when crossing a busy street. They can also make residential streets safer and more pleasant for everyone who lives on them by reducing speeding and inattentive cut-through drivers.

They can be much cheaper than protected bike lanes, cycle tracks, or other solutions that physically separate bikes from cars, though that also depends on how each is built. But greenways can be implemented relatively quickly and inexpensively, and they can make a big difference in just a few short years towards making a city feel more humane.

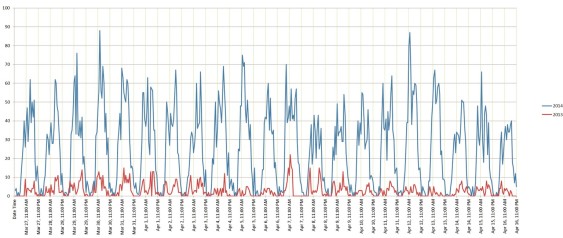

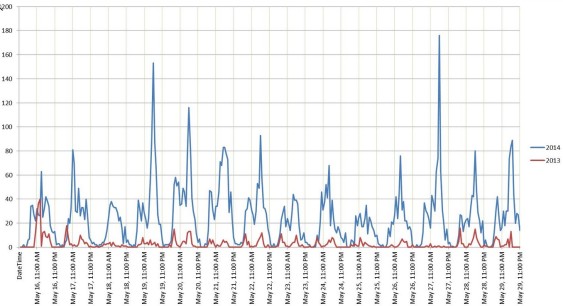

They’re also popular. SDOT recently released data (with more to come) showing that daily bicycle traffic on the NW 58th Street greenway increased by 805 percent in the first year after its installation (from 64 weekday cyclists in 2013 to 579 in 2014).

In West Seattle’s Delridge neighborhood, bicycle traffic increased by 635 percent on the 26th Avenue SW greenway (from 86 weekday cyclists in 2013 to 632 in 2014.)

These numbers alone don’t tell us whether the greenways are attracting new cyclists or whether longtime riders just shifted over from another route. In fact, a recent study from Portland found that living near a neighborhood greenway did not make a parent more physically active or more likely to take a bike trip. (The study does have important caveats, though, primarily that it may have collected data too soon to pick up longterm behavioral shifts.)

That leads to one of the critiques of greenways: That they can make it easy for a city to abandon doing the harder, more expensive, and necessary work of improving commercial streets and busier thoroughfares for cyclists. Why irritate businesses and drivers by removing parking on a busy street when they can point to a neighborhood greenway three blocks away and argue it’s good enough?

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2012/07/12/babes-on-bikes/”,”title”:”Biking with your little ones? Take some inspiration and tips from our reader photo essay.”}’ color=”green”]

Some bike advocates debate whether greenways should even count as quality bike infrastructure. They don’t separate bikes and cars, and they don’t do their job if a city skimps on measures to curb automobile traffic. Plus, cyclists traveling on residential networks may be less visible to drivers, politicians, small business owners, and people who might be on the bubble about biking but want safety in numbers. That can potentially make it harder to build support for other parts of a complete biking network, and possibly even to attract new bikers who aren’t in the know about where greenway routes are.

In a perfect world, building neighborhood greenways vs. bike lanes vs. urban trails shouldn’t be a zero sum game (though when budgets are involved, it always is to some extent.) Portland officials like to compare greenways to a city’s bus network—abundant, utilitarian, cheap—and bike paths and protected bike lanes to a rail network that carries a lot of people on centralized routes. Each serves a different, yet equally important, function in building an achievable and complete transportation network.

If car traffic is adequately addressed, greenways can absolutely improve the quality of life for people who live near them. And if I’m any judge, a connected network of them (which Seattle is still far from) probably can help attract the “interested but concerned” biking demographic. After repairing the garage door that made it hard for me to use my bike, I’m excited to be on it again. I got a kickstand that works, some reflective vests, 24 fully functioning gears, and a new bike seat post so I can now hitch my kid’s trail-a-bike to mine. And thanks to the improvements that Seattle has made since she was born, we’ll actually use it.

Comments are closed.