Cloud Peak Energy—a major coal producer in the Powder River Basin, and one of the top coal exporters in the western US—will release its third quarter financials in a few weeks. And even though international coal prices have been in free-fall for almost three years, I expect that Cloud Peak’s financial reports will show that the company’s export (or “logistics”) division made money from June through September 2014.

Yet I also expect that, just beneath the surface, the firm’s financials will show that Cloud Peak lost money exporting coal to Asia, just as it has for the last four consecutive quarters.

Just beneath the surface, Cloud Peak’s financials will show that the firm lost money exporting coal to Asia—just as it has for the last four consecutive quarters.

So how is it possible for a coal company to report profits from its export division, but losses from actual export sales? The answer: even though Cloud Peak’s coal export sales are bleeding red ink, the company is still benefiting from big bets that the company made years ago on the coal futures market.

But I believe that those lucky bets are poised to run out, starting in 2015.

According to the company’s financial records, as well as public statements by executives, Cloud Peak used the futures markets in 2012 and 2013 to “hedge” against the possibility that coal prices could fall. Back then, before the Asian coal bubble had deflated, coal prices were still high enough that Cloud Peak was virtually guaranteed to profit from selling coal. So the company used futures contracts to, in effect, lock in the prices they’d receive in the coming years.

In some ways it was a risky gamble: if prices were to rise instead of falling, those futures contracts would turn into a liability, limiting the firm’s profits from exporting coal to Asia.

But as it turned out, hedging was a smart strategy. As we’ve reported before, Asian coal prices have tumbled in fits and starts for three and a half years. And as coal prices fell, Cloud Peak’s “hedges” started yielding greater and greater returns.

At first, for 2012 and half of 2013, Cloud Peak’s hedging gains simply represented extra profits; the company was still reporting making money selling coal to Asia.

But starting in the third quarter of 2013, those hedges saved Cloud Peak’s bacon: without them, the firm would have started reporting losses. That’s because prices in Asia’s coal markets had fallen so low that Cloud Peak coal—which can cost $50 or more per metric ton to move from the mine mouth all the way across the Pacific—simply couldn’t earn a profit in Asian markets.

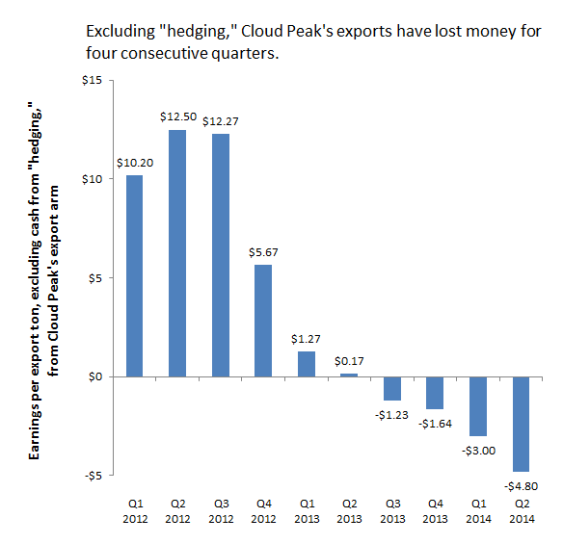

The chart below shows Cloud Peak’s reported earnings per export ton from the company’s logistics division, excluding money earned from hedging.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

As you can see, after excluding cash gains from hedging, Cloud Peak’s export division started reporting losses in the third quarter of 2013. That’s when prices for comparable Indonesian coal started to fall below $60 per ton. (It’s worth noting that Cloud Peak started exporting coal to Asia back in 2010, when the price for Indonesia’s so-called “Envirocoal” brand was just poking its head above $60 per metric ton. “Envirocoal” is very close in energy and sulfur content to Cloud Peak’s coal.)

For the second quarter of 2014, Cloud Peak’s export division reported nearly $5 in losses per ton of coal exported. And international prices have only fallen lower since then—strongly hinting that Cloud Peak could be facing even steeper losses in the the third quarter.

Still, the company has a substantial “hedge” position that should carry them over through the end of 2014. As of mid-year, the company’s hedges for the remainder of 2014 were worth nearly $15 million—which should be enough for Cloud Peak’s export division to report a profit for the second half of the year, even if it’s selling coal at a loss.

But Cloud Peak maintains a far less robust set of hedges for 2015, and fewer still for 2016. At last count, Cloud Peak’s hedges were worth only about $2.7 million per quarter in 2015—a level that will probably leave the company’s export arm losing roughly $2 to $3 million per quarter, and possibly more. And unless the Asian coal bubble somehow reinflates, Cloud Peak’s export losses could only deepen in 2016.

Cloud Peak’s export strategy worked when prices were high, because the company could use futures contracts to lock in prices and guarantee profits. But as prices have fallen back down to earth, the company’s exports could start weighing on the company’s bottom line. And the firm has run out of room to hedge: hedging only works if it lets you lock in high prices, but in today’s coal futures market the best that Cloud Peak can hope for is to use hedging to limit the firm’s export losses.

Yet even with prices as low as they are, Cloud Peak may have no choice but to continue exporting coal at a loss: Cloud Peak has locked itself into long-term commitments with rail and port operators which will guarantee that the company will lose even more money if it stops shipping coal to Asia. That would put the company in a Catch-22—they could lose money whether they export or not.

And if that happens, as is looking increasingly likely, many of Cloud Peak’s investors will wish the company had never embarked on its risky export strategy.

Michael Riordan

What’s the current price per metric ton of thermal coal, FOB Newcastle, as of today?

Clark Williams-Derry

The October futures price (which is basically the same as the spot price), along with all other FOB Newcastle futures contracts, can be found here.

Clark Williams-Derry

At the moment, the October Newcastle contract price is $64.10. That’s at least $16 per ton below the price point at which Cloud Peak has said that the company can break even on coal sales to Asia.