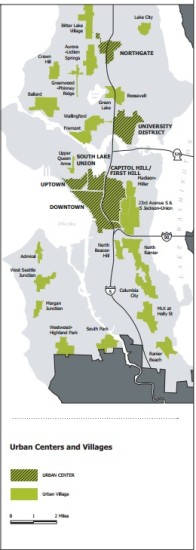

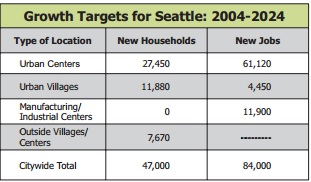

At last count, Seattle ranked as the fastest growing major city in America. The city’s growth has easily outpaced the projections of its decade-old Comprehensive Plan, which foresaw 47,000 new households (as well as 84,000 new jobs) between 2004 and 2024. Between 2005 and 2012 the city added 29,330 net new housing units—roughly 62 percent of its 2024 target in just 7 years.

This rapid growth has stemmed in large part from the city’s relatively robust economy. From March 2013 through March 2014, for example, King County (which includes Seattle) ranked fifth among all US counties in net job growth, trailing only the likes of Los Angeles County and Manhattan.

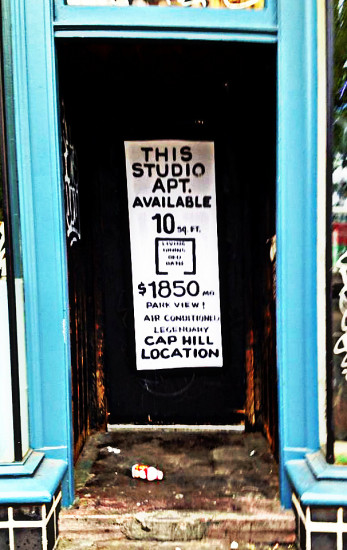

But the population boom has sent housing prices and rents trending upwards—creating real anxiety among many renters, and fears that Seattle’s housing market will price out residents that once could afford to live in the city.

One city councilmember has described today’s housing market as being in “crisis,” and the mayor has launched a housing affordability advisory committee aiming to make affordability recommendations by next March. (Full disclosure: Sightline Executive Director Alan Durning will serve on it.)

Zoned Out?

Very little in municipal policy creates as much controversy as zoning. Attempts to relax exclusionary housing rules—through upzones, unregulated microhousing development and other forms of inexpensive housing, or reducing the requirements to build parking for new housing—typically encounter resistance from existing residents. Because it’s often hard to change these exclusionary housing rules, municipal governments often turn to inclusionary zoning to try to soften the impact of exclusionary housing policies. But many developers (and some credible academics) view inclusionary zoning largely as a tax that adds to housing construction costs and stunts supply, which can ultimately boost rents rather than reducing them.

Discussions of housing affordability often revolve around questions of zoning—rules about who can build what kind of housing, where, with what sort of restrictions or requirements attached. Which raises some questions: where did zoning come from, and how do different places use it?

Zoning: Exclusionary and Inclusionary

Today zoning stands as the biggest blind spot of urban greens. But zoning of any kind is a relatively new practice in the United States. The nation’s first zoning codes originated in New York City in 1916, spurred by neighbors who opposed new high-rises. The use of zoning quickly spread to other municipalities. In 1926 the United States Supreme Court upheld the practice of zoning, ruling that the zoning laws of Euclid, Ohio, passed constitutional muster.

Many (but not all) of these early zoning programs were both racist and classist. They were largely created to keep “undesirable” people and development away from higher-income neighborhoods, by restricting both the types of housing that builders could build, and by restricting the kinds of people who could live in them. Over time, municipalities used zoning to reserve large swaths of their total land area for single family houses with ample yards—a particularly expensive form of housing, and one that limited the number of lower-income people who could afford to live near the well-off.

As a reaction to this sort of “exclusionary” zoning, in the early 1970s US municipalities began to adopt “inclusionary” zoning policies, which attempt to ensure that when new housing is built, developers provide low-cost housing for at least some residents. The first inclusionary zoning policy, passed in Fairfax County, Virginia in 1971, mandated that developers of more than 50 units of multi-family housing provide 15 percent of their units at prices that were affordable to residents within 60 to 80 percent of median income. In 1973, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned the ordinance, asserting that it was a “taking” of property rights without fair compensation. (See Fairfax County v. Degroff.) Nonetheless, in 1973 nearby Montgomery County, Maryland, passed a “moderately priced dwelling unit” ordinance, which required developers of more than 50 residential units to set aside 12.5 to 15 percent of total units, dispersed throughout the property and available to families with 50 to 80 percent of the area median income. It is still active.

The Montgomery County, Maryland, ordinance is the oldest in the United States. But California, with over one hundred ordinances and 30 years of experience, has the most familiarity with inclusionary zoning. The Bay Area standard bearer is Palo Alto, which first instituted its program in 1973. Today, more than 100 communities in California have similar zoning statutes. Nationally, the ordinances can also be found in Colorado, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, amongst other states.

Since 1999, Oregon jurisdictions have been prohibited from enacting mandatory inclusionary policies. Passed by the Oregon legislature, the prohibition was favored by home-builders and realtors who worried that inclusionary policies would hurt local housing markets. Oregon and Texas are the only two states that prevent municipalities from having a mandate on developers to provide subsidized housing in new construction.

Municipalities in British Columbia were among the first in Canada to adopt inclusionary zoning policies. Since 1988, Vancouver has required 20 percent of the units in major residential projects to be set aside for subsidized housing units.

Today, inclusionary zoning programs come in all shapes and sizes. Some offer incentives, such as the right to build more housing on a given property, provided that developers set aside some units that will be offered to lower-income people at below-market rates.

The Sunset Electric Apartments in Seattle’s trendy Capitol Hill neighborhood were one of the first major projects in the area that took advantage of Seattle’s 2009 preservation incentive program, which granted developers a fifth floor of residential units in exchange for keeping the original 1926-constructed outer facade.

Other programs require developers to include below-market units in every new housing development. Some give developers a choice between building new units and paying into a municipal fund dedicated to building low-rent units. Inclusionary zoning programs differ in the types of development covered, the share of new units required, the required price for new rental units, who can obtain low-cost units, and the length of time that “affordable” units must be offered at below-market rates.

Many of these zoning programs require below-market units to be of similar size and quality as the market-price units, and also spread throughout the project to avoid creating conspicuous public housing or “projects”. However, New York City developers recently have generated national opprobrium by offering affordable units accessible only through “poor doors” separated from main entrances for market-rate units.

Seattle, like other cities grappling with rising home prices, is right to publicly discuss the merits of its various housing incentive programs. But leaving aside questions around inclusionary zoning, it’s clear that exclusionary housing policies still have a major effect on housing costs. No robust and honest debate on urban housing issues can avoid a thorough discussion of the ways that existing housing, parking, and zoning policies restrict the supply of low-cost housing—raising housing costs for everyone in the city.

Comments are closed.