Editor’s note January 2017: Are you participating in this morning’s #ClimateFacts “Twitter storm” (details here)? We are! And we’ll look forward to keeping up the drumbeat for climate science and activism in years to come, on our Twitter feeds and elsewhere. Of course, how we message is just as important as what we message, so we’re re-posting this helpful one-pager of best practices for powerfully communicating our climate priorities. Onward, fellow climate messengers!

Sometimes those of us who are very deeply immersed in climate communications become so focused on crafting messages that effectively convey certain complex issues, ideas, and policy measures that we forget some of the most fundamental communications rules.

I speak for myself. I should probably stick a Post-It note on my computer screen with a checklist: Is it first and foremost about people? Emotions!! Are you going for the gut or brain? Did you say it in plain language? (In fact, I’m making that sticky note right now).

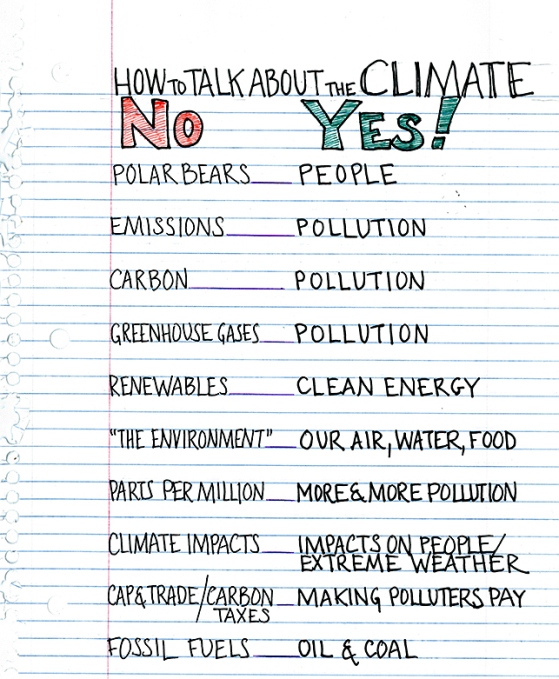

Based on those most basic, simple yet powerful rules of thumb, Jeremy Porter, a super-smart freelance communications strategist (Jeremy Porter Communications), has summed up nicely how to talk about climate change so that people will care. Noting that most people don’t care at all or very much (or don’t have the time or energy to), Porter insists that it’s not a matter of piling on more facts nor a question of saying “global warming” instead of “climate change.” Instead, we can make global warming more relevant to people by talking about why it matters to them, their families, and their daily lives. One of Porter’s examples really hit home: People don’t want a “safe climate” or a “healthy climate”. They want to be safe and healthy.

Porter reminds us that the language we use to communicate about climate change needs to be simple and uncontroversial. A word like pollution, for example, works better than “carbon emissions.” A person does not have to believe in or understand global warming to care about these things. “People understand pollution,” he explains, “They don’t like it, they think there should be less of it, and they understand it’s bad for their health.”

Porter’s cheat-sheet could almost fit on a sticky note, but a Flashcard works better. (I invite you to stick it somewhere front and center, so you’ll see it as you work.)

The guide is adapted from Jeremy Porter’s guide. His communications recommendations are based on research and recommendations by Drew Westen, professor in the Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry at Emory University and founder of Westen Strategies, LLC, and partly based on research conducted by Jeremy Porter with Alex Frankel & Associates.

Download Jeremy Porter’s original one-page guide here: How to talk about the climate. And check out his blog here: jrmyprtr.com.

Comments are closed.