Carbon pricing’s time may have come. California Governor Jerry Brown is crusading for climate regulation, Washington Governor Jay Inslee is considering cap and trade, and government leaders in Oregon are contemplating a carbon tax. New US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) carbon regulations may drive states across the country to join the Northeast’s well-established cap-and-trade program.

What’s that you say? You didn’t know the Northeast has the oldest carbon pricing program in the US?

Despite years of seamless market operations and nearly $1 billion in auction revenue reinvested in the local economy, the Northeast’s Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI—pronounced Reggie) has gone largely unnoticed out here in the Northwest.

So here are four things that will help you understand RGGI.

(1) RGGI has been operating seamlessly for years.

RGGI was established in 2005, held its first auction of CO2 allowances in 2008, and the cap was implemented in 2009. After a 2012 program review, the states agreed to an Updated Model Rule in 2013. RGGI has held 24 quarterly auctions to date, selling more than half a million allowances and collecting nearly $1 billion in auction revenue. All that, with nary a hint of market manipulation or price volatility.

(2) RGGI is a multistate cap-and-trade program.

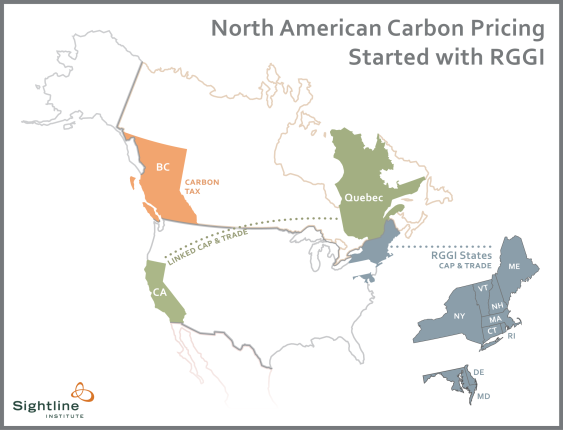

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

Nine Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states participate in RGGI (currently: Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. New Jersey was originally a member but dropped out in 2009. That withdrawal was overturned in court, so New Jersey may rejoin). To participate, each state signs a memorandum of understanding and then enacts its own statute and regulations—modeled after the RGGI Model Rule—establishing a state cap-and-trade program. Although states may distribute their own allowances (tradable in every participating state), most just use the central quarterly auction.

(3) RGGI only covers CO2 emissions from in-state electricity generation.

RGGI covers emissions from in-state power plants that are at least 25 megawatts. Electricity emissions are only 22 percent of CO2 emissions in the nine states, compared with the national average of nearly 40 percent. If new EPA rules drive other states to join RGGI, its impact will grow.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

RGGI also does not cover imported electricity—electricity generated outside the RGGI states but used by homes or businesses inside the RGGI states. This raises the concern that RGGI states could cut in-state dirty power but increase imports of dirty power from out of state, in effect “leaking” emissions across the border. Only about 10 percent of RGGI electricity sales come from imported power, and the Congressional Research Service says RGGI has not leaked yet.

RGGI does not cover other greenhouse gases, such as nitrogen oxides, both of which are covered in California.

(4) RGGI is designed to keep the price low and steady.

Cap-and-trade programs and carbon taxes use the market to cut carbon pollution. With cap and trade, the pollution limit is certain but the price is not; with a tax the price is certain but the reductions are not. Cap-and-trade programs use “cost containment” mechanisms to give emitters more certainty about the price and more flexibility in responding to it. RGGI’s cost containment mechanisms include:

- Three-year compliance periods. Complying every three years rather than every year lessens price volatility by smoothing out annual variations in the weather or the economy.

- Soft price ceiling. If the auction price exceeds certain price triggers ($4/ton in 2014, rising to $10.75/ton in 2020), allowances are released from the “cost containment reserve” (CCR) to dampen the price. This feature, added with the 2013 update, was triggered in the March 2014 auction, but not in the June auction. Unlike California’s reserve, which takes allowances out of future periods, the CCR allowances are extra, so they raise the cap. Because they are limited (only 5 million in 2014—about 5 percent of the cap—and 10 million per year thereafter), they don’t increase emissions as much as a “hard” price ceiling would by releasing unlimited allowances to keep the price below the trigger.

- Price floor. RGGI’s minimum auction price (currently $2/ton) and its soft price ceiling create certainty that allowances will likely trade within a fairly narrow range.

- Banking. Emitters can hold allowances and use them later. (RGGI prohibits borrowing allowances from future periods. This prevents procrastination, forcing emitters to start cutting pollution from the outset.)

- Offsets. Power producers can use offsets—greenhouse gas reductions from other sectors, such as landfills and forests—to account for up to 3.3 percent of their emissions. California is more generous, allowing offsets for up to 8 percent of compliance obligations.

Tomorrow, in Part 2, I’ll list six lessons Cascadia can learn from RGGI.

Charts designed by GoodMeasures.biz with data from EPA State Energy CO2 Emissions.

Sam Bliss

Thanks for writing this post! It’s amazing how little I know about the Northeast’s (sort of) cap and trade (at prices guaranteed low enough not to move the market).

Is $4 a ton really enough to make businesses think they’re doing something good, just enough to make policymakers believe their region is a leader, just enough to make everyone exhale and say “if only every state could be just like us”? It’s not quite enough to change prices markedly and thus consumer behavior, not quite enough to make polluters (jobs) flee New England — which would allow policymakers to see the flaw, that a localized cap-and-trade system encourages ‘exporting’ pollution to places without strong climate policy. Basically, even the 2020 ceiling $10.75/ton is not nearly enough to reduce emissions at the rate necessary to beat climate change.

But what would happen if carbon were taxed at $100/ton? This would be closer to what an economist might call the ‘true’ social cost of carbon (this is not to imply that there are ‘right’ answers in economics, only that economists seem to think so). $100/ton would do a better job getting us toward an ‘efficient’ level of greenhouse gas emissions (again, the notion of an efficient amount of pollution is a myth). Gas would go up $1/gallon, electricity and food would cost more, businesses would find their production less profitable when without a free atmospheric waste dump, and jobs would be lost. Increase unemployment, raise prices on everything — what would that bring about? An uproar!

The only reason our society can function at all with such wide wealth inequality is because our economy runs on artificially cheap dirty energy. We can have a large underclass of poor people because things are cheap — not just dirty energy thanks to fossil fuel subsidies both implicit (no carbon tax, free natural resources) and explicit (direct payment), but also cheap processed food thanks to corn and soy (and oil) subsidies, cheap clothes thanks to under-compensated labor in horrible working conditions in Bangladesh. If all this ‘cheap’ stuff — cheap in price but not cost to society, mind you — became more expensive overnight, it would be clear very quickly that we need to spread the money around a bit more evenly, even if only to avert a revolt much bigger and angrier than the Occupy movement.