[prettyquote]“Should an incident occur within or near a densely populated area … an incident … has the potential to be truly catastrophic and result in billions of dollars in personal injury and property damage claims. The damages potentially resulting from an exposure could risk the financial soundness and viability of the rail transportation network in North America.” The Association of American Railroads (AAR), Submission to Transport Canada, January 2014. [/prettyquote]

Bakken crude oil production has many of the classic characteristics of an economic bubble. It looks likely that, as with every bubble before, it will end. Whether it ends catastrophically or just badly depends on how regulators act.

Some of the primary features of a bubble include a very rapid market expansion based on an unrealistic assessment of underlying risk, lax regulation, and an overly optimistic belief in continued rapid growth. In hindsight, it should have been obvious that hundreds of billions of dollars of poorly hedged sub-prime loans that depended on ever-rising housing prices were a huge risk. When the sub-prime mortgage bubble burst, the entire financial system was so distressed that a government bailout was required to save it. On a smaller scale, the same might be said for shipping huge amounts of explosive shale oil in unsafe, poorly insured tank cars through hundreds of populated areas: the risks are obvious but poorly hedged, and the enterprise can result in tremendous negative consequences for communities. In a realistic worst-case scenario, the Bakken oil train bubble bursting catastrophically could jeopardize the viability of the North American rail transportation network.

The mechanism most likely to pop the Bakken bubble is an Emergency Order issued by the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) that immediately removes unsafe legacy DOT-111 tank cars from use in oil trains. An executive order like that—already thoroughly justified and well within USODT’s authority—would severely curtail oil production in the Bakken region because there is no alternative method for shipping the volumes of oil currently being produced.

The real question may be “when,” not “if,” USDOT will issue the order. Deborah Hersman, the recent chair of the National Transportation Safety Board urged regulators not to wait for “a higher body count before they move forward.”

Regulatory authority and an imminent hazard

The US federal government regulates railroad safety via agencies under the USDOT umbrella. (Local and state government laws are preempted from regulating railroads.) The Secretary of USDOT has the authority to impose Emergency Orders on railroads upon determination that “…an unsafe condition or practice, constitutes or is causing an imminent hazard.” In other words, USDOT Secretary Anthony Foxx has the authority to skip an extended “rulemaking” process and simply issue an Emergency Order banning the use of legacy unsafe DOT-111 tanks cars for transporting crude oil.

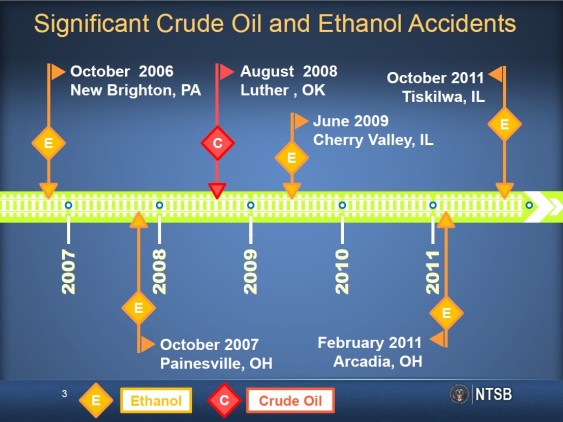

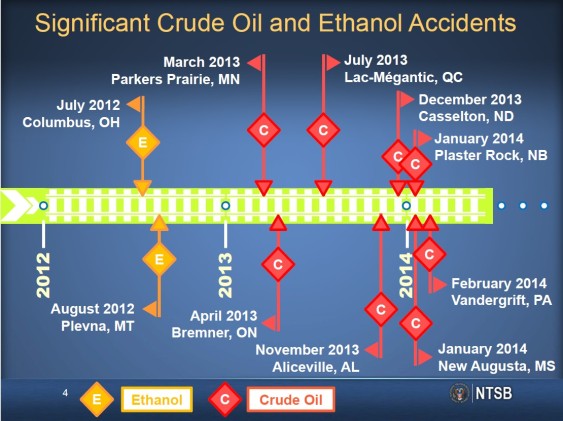

Hersman’s former agency, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), conducts independent crash investigations, but lacks regulatory authority. And since the 1990s, the NTSB has investigated and documented accidents involving legacy DOT-111 tanks cars. According to the NTSB, legacy DOT-111s can ”…almost always be expected to breach in derailments that involve pileups or multiple car-to-car impacts.”

So why are these older unsafe cars still on the rails? In part because a provision in federal law making railroads operate under a “common carrier obligation.” Railroads are, in fact, actually prohibited by law from refusing to haul any legal load, even if would be inconvenient or unprofitable. Or dangerous. So oil companies load unstable crude into legal (but unsafe) tank cars and the railroads must haul them, and they will continue to until federal regulators determine these tank cars are no longer okay to use.

Railroad workers generally do an excellent job of moving cargo through cities without incident. Yet accidents do occasionally happen. And oil trains will derail just as freight trains derail, except the consequences can be much more severe. In May, Grays Harbor County in Washington, the location for a proposed oil-by-rail train terminal, experienced three freight train derailments within a two week period. Sightline mapped every derailment in the Northwest from June 2011 to December 2013 and found that on average one freight train derailment occurs every three-and-a-half days.

And derailments and releases of crude oil have increased dramatically as oil-by-rail traffic has increased.

There is a well-documented risk of imminent hazard from oil train derailments. And to a certain degree the USDOT recognizes this. On May 7, on the heels of yet another oil train explosion-–-this one in Lynchburg, Virginia—it issued a voluntary safety advisory urging that Bakken crude not be shipped in legacy DOT-111 tank cars. Transport Canada, the Canadian railroad regulator, has moved somewhat more assertively. It recently issued its version of an emergency order to immediately prohibit the use of 5,000 of the least crash-resistant legacy DOT-111 tank cars for the shipping of hazardous material including crude oil. Though prohibited in Canada, these tank cars are still perfectly legal for shipping hazardous materials and crude oil in the US. In addition, Transport Canada will require that all legacy tank cars used for the transportation of crude oil and ethanol be phased out of service or retrofitted within three years.

It doesn’t take much imagination to believe that USDOT’s passivity so far results from push back by the oil industry that fears losing shipping capacity.

Systemic risk and a catastrophic oil train accident

“Systemic risk” is a term for the risk of a collapse of an entire market caused by the failure of one big institution. After the searing experience of the 2008 financial meltdown, the federal government put into place regulations ensuring that financial institutions had the capitalization they would need to handle their own potential losses in a worst case scenario event, instead of depending on the government for a bailout.

Yet today’s railroad industry is every bit as exposed to systemic risk as the finance sector was then due to a combination of their common carrier obligation and a liability regime that imposes all costs from a worst-case oil train derailment on the railroad. The billions of dollars in personal injury and property damage claims from a catastrophic derailment in a populated area could, according to the American Association of Railroads, “risk the financial soundness and viability of the rail transportation network in North America.”

At most, a Class 1 railroad has $1 to $1.5 billion in liability insurance — far less than what is needed for a worst-case accident. “Insurance should be recognized for what it is; an inadequate secondary layer of protection,” the Canadian Pacific railroad told Transport Canada in its investigation of systemic risk in the railroad industry. Right now, the primary layer of protection is the taxpayer.

The oil companies profiting from the Bakken boom are creating this systemic risk by shifting all risk and costs from a crude oil train derailment onto under-insured railroads and the public. When questioned about this, oil companies like Valero blithely respond that a railroad “bears this responsibility and has the duty to ensure carrying a sufficient insurance coverage. Should insurance premiums increase, the market will adjust and the ‘user pays’ principle will continue to apply.”

But the oil companies well know that even if a railroad wanted to buy insurance for a truly catastrophic accident—a 300 foot-tall fireball in downtown Spokane, say—no one would sell it to them.

“There is not currently enough available coverage in the commercial insurance market anywhere in the world to cover the worst-case [train derailment] scenario,” according to an industry expert quoted in the Wall Street Journal.

Taxpayers will inevitably be forced to pick up the billions in uninsured costs from a catastrophic oil train accident to prevent the bankruptcy of a Class 1 railroad and maintain the viability of rail transportation in North American.

The systemic risk produced by each and every trip a crude oil train makes through a populated area certainly should be a reason to prohibit the use of legacy DOT-111s.

The Bakken Bust

The rapid increase in oil-by-rail has largely been to serve shale oil production out of the Bakken region where there is a lack of pipeline infrastructure.

According to the oil industry, there are about 26,000 legacy DOT-111s in crude oil service now, making up 70 percent of the current fleet. Based on oil industry statements, shippers are not planning to pull even a single one of these from service by the end of 2015. To the contrary, the oil industry expects that legacy DOT-111 tank cars “could be needed for the next decade if the industry is going to meet the challenge of moving booming crude production to markets.”

If legacy DOT-111 tank cars are eventually prohibited by Emergency Order – whether before or after the next disaster—it will inevitably reduce crude oil shipping capacity. In fact, industry representatives have warned “that the railway supply industry will have a hard time meeting the rising demand for new cars while retrofitting existing ones.” Shippers looking to buy rail cars are already facing a two-year backlog in some markets.

Without the nearly 26,000 older, unsafe legacy tank cars, Bakken production will be forced to decline dramatically simply because there will be no way to move the crude to refineries in sufficient volume. So right now, the oil industry is doing everything it can to prevent an Emergency Order including, ordering up a study alleging that, despite all the online videos of oil train derailments and resulting fireballs, Bakken oil is actually no more flammable than other commonly shipped hazardous materials, and it is perfectly fine to ship in legacy DOT-111s.

It’s very likely that an Emergency Order on legacy DOT-111s is coming—whether proactively issued by USDOT out of regard for public safety, or after the next big oil train accident. And if it requires an immediate phase-out of all the legacy tanks cars, the Bakken bubble will burst.

Comments are closed.