If you’re a coal junkie, you’ve probably read quite a few press accounts touting the bright future for Powder River Basin coal. This story from Gilette, Wyoming, for example, predicts a resurgence in demand for the low-rank coal produced in the region. This one argues that coal is making a comeback, after years of losing ground to natural gas. This one forecasts “tremendous” demand for the region’s dirtiest fuel. I could go on and on.

Articles of this ilk generally offer breathless quotes from coal industry executives, and point to a few factors, such as rising natural gas prices or the cold winter, that make a rapid rise in coal demand seem plausible.

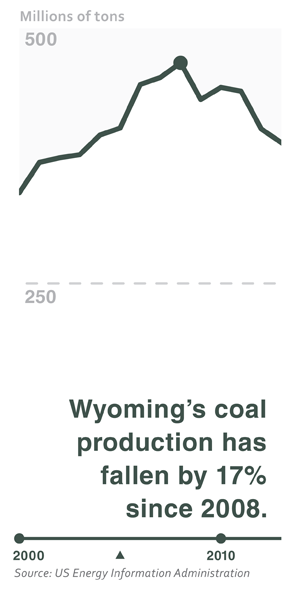

But what these articles don’t do is provide much supporting data. And when you look at the actual production figures from Western coal country, a very different story emerges. After peaking in 2008, coal production in Wyoming has fallen by 17 percent.

And if I’m right, those trends won’t be reversing themselves any time soon.

I should be clear here: it’s quite possible that Wyoming coal producers will boost production over the next year or so. Many of the nation’s coal-fired power plants burned down some of their coal stockpiles during the exceptionally cold winter, and are now buying extra coal to replenish their stocks. And we already see higher coal prices, which could lead to a modest boost in coal output.

But the longer-term trend isn’t looking good for the major producers in the PRB.

Take Cloud Peak Energy, the only major coal company that operates exclusively in the Powder River Basin. The company has announced that it will start trimming production at its Cordero Rojo mine by about 10 million tons per year, starting in 2015. The company plans to redeploy some of the equipment from Cordero Rojo to its better-performing Antelope mine. Even so, executives have all but ruled out significant production growth at Antelope; the equipment moved from Cordero Rojo will merely help to stem production declines, not boost output.

Cloud Peak’s management projects that the cuts at Cordero Rojo will reduce Cloud Peak’s annual output from about 90 million tons per year down to about 80 million tons. In short, Cloud Peak has begun to prepare the company’s shareholders to accept shrinking coal volumes as the new normal.

Arch Coal, another major PRB producer, is sending out similar signals. In their most recent 10-K filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the financially troubled firm admitted that the coal reserves at its largest Wyoming mine, Black Thunder, will only hold out for another six years at present mining rates, but could begin tapering down even sooner than that:

Without the addition of more coal reserves, the current reserves could sustain current production levels until 2020 before annual output starts to significantly decline, although in practice production would drop in phases extending the ultimate mine life.

Industry observers point out that the new reserves near Black Thunder may be as much as 400 feet underground—which would entail sharp increases in mining costs that could squeeze Arch’s profits, or simply make the coal uneconomic to mine.

As with Cloud Peak, Arch is preparing its shareholders for flat or declining coal production. Back in February Arch’s CEO said: “I don’t think there’s the excess capacity on the PRB that maybe people think there is.” And referring to the increasing difficulty and cost of mining in the PRB, Arch’s COO added: “[T]his isn’t the basin I left 7, 8, 10 years ago. It’s not quite as easy to turn up the production as it was then.” And like Cloud Peak, Arch is proud to point out that it’s keeping capital spending to a minimum—as clear a sign as any that the company has no plans to spend the considerable sums needed to boost output.

As if we needed more evidence that Wyoming’s production is well past peak, consider the nearly unprecedented failure of two federal coal lease offerings last year. In one, officials from the Bureau of Land Management rejected the sole bid—a paltry 21 cents per ton for federally-owned coal—as too low. The other lease offering received no bids at all. Apparently, the major PRB producers believe that the coal that’s now on offer is simply too expensive to mine profitably. So even as production at existing mines is flat or declining, the industry is doing very little to find new supplies.

So while it’s possible that Wyoming’s coal production could rise a bit this year, the long-term trends bear little resemblance to the coal “renaissance” that credulous reporters sometimes talk about. Looking just a few years out, the prospects for Wyoming coal productions still look quite dour…and a return to the seemingly endless boom of PRB coal production is looking more and more like a pipe dream.

David MacLeod

Nice to see a post on Peak Coal, which is not much talked about. I believe coal export terminals, if constructed, will quickly beocome stranded assets. Richard Heinberg’s 2009 book “Blackout: Coal, Climate, and the Last Energy Crisis” is a good place to start when looking at this topic. Reviewed by David Roberts at Grist: http://grist.org/article/2009-07-27-blackout-heinberg-on-dwindling-coal-reserves-and-the-siren-song/