There’s been a fair bit of ink spilled lately about whether the new and proposed vehicle license fees in Seattle and King County are regressive or progressive. In fact, even local advocates for low income people disagree. John Fox says they’re bad, but Tim Harris says they’re good.

What’s the right answer?

It depends what you mean. But with new census data out, I’ve got an excuse to make some charts. Take a look.

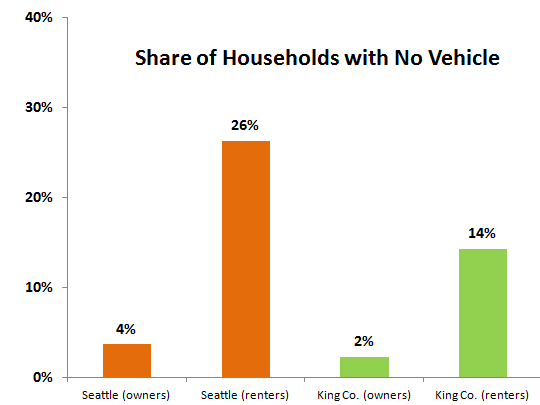

Not surprisingly, households that rent are drastically more likely to be carless than households that own. I was surprised, however, to find that more than 9 percent of all King County households—over 74,000 households—do not have a vehicle. In Seattle, carless-ness is even more prevalent: nearly 1 in 6 households in the city do not have a car.

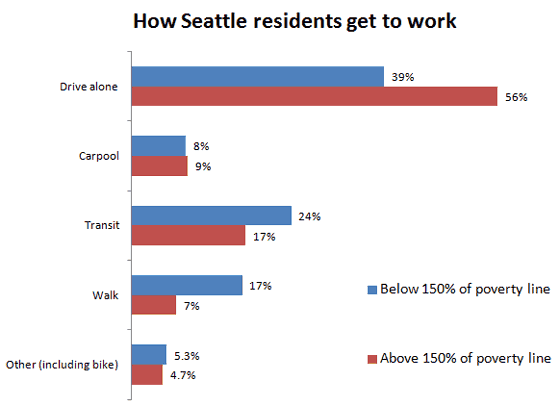

In Seattle, non-poor residents are far more likely to drive. They drive alone to work in much greater numbers and, in fact, are also slightly more likely to drive with someone else in the car. Low income people, by contrast, are far more likely to rely on buses or sidewalks to get to their jobs. Low income people are also a hair more likely to be counted as using “other” modes of transport, a category that includes bicycles, motorcycles, and taxi cabs.

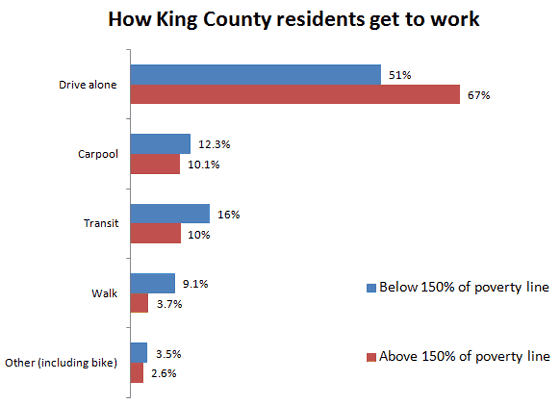

A similar story plays out in King County. Non-poor residents are much more likely to commute in their cars, while low income people are more likely to carpool, take transit, walk, or use other modes of travel.

The problem, I suspect, is that people mean somewhat different things by “regressive.” We normally think of flat fees as regressive, but there are limits to that way of thinking. A flat fee on caviar, for example, would hardly fit the definition. Cars aren’t exactly a luxury good for many people, yet there’s every indication that low income households in Seattle and King County are less likely to own vehicles or to rely on them to get to work. Low income residents are far more likely than the non-poor to rely on transportation alternatives for their commutes.

By my way of thinking, determining whether something like a vehicle license fee is “regressive” depends a great deal on how the revenue gets spent. If it’s plowed into car infrastructure, I’m tempted to say it’s a bad deal for low income folks. But if the funds supplement bus service, walking, and other options, I’m more likely to believe that the net effect is economically progressive.

*** Postcript: Please see my follow-up post that digs in a bit more. I think it makes the point a bit more clearly!

Notes: All data come from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey 2010 data set. Figures for King County are inclusive of Seattle. Big thanks to my colleague Jennifer Langston who did some of the research for this post.

Also, Seattle councilmember Mike O’Brien had the city’s demographer produce some fascinating income-based pie charts of car ownership. I wasn’t able to reproduce that analysis (either because the most recent data don’t allow it or because the city’s demographer has better Census data-crunchin’ powers than I’ve got), but it’s worth checking out.

Comments are closed.