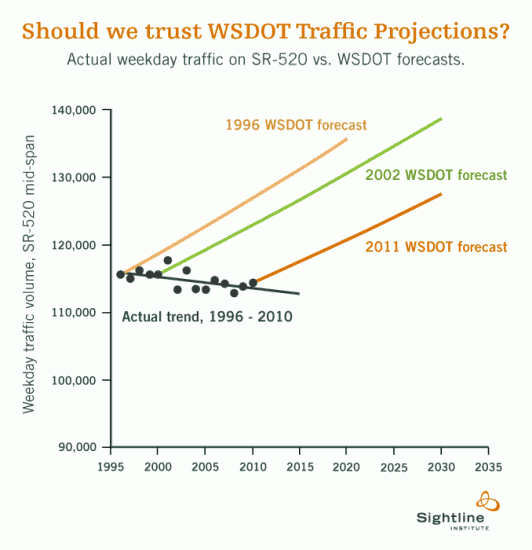

I wish I were making this up. The Washington State Department of Transportation continues to insist that traffic volumes on the SR-520 bridge across Lake Washington are going up up up—even though actual traffic volumes have been flat or declining for more than a decade! Here’s a chart that makes the point.

In a charitable mood, you could forgive the 1996 projections. Back then, rapid traffic growth on SR-520 was a recent memory: up through about 1988, traffic growth was both steady and rapid.

By 2011, however, it should have been perfectly obvious that the old predictions were proving inaccurate. Yet WSDOT just kept doubling down on their mistakes—insisting that their vision of the future remained clear, even as their track record was looking worse and worse. So now they’ve wound up with an official traffic forecast, in the final Environmental Impact Statement no less, that doesn’t even pass the laugh test.

It would be funny—if the state weren’t planning billions in new highway investments in greater Seattle, based largely on the perceived “need” to accommodate all the new traffic that the models are predicting will show up, any day now.

In case you don’t believe me about the numbers, feel free to check out the sources directly. I’d be happy to be corrected.

The data on recent traffic volumes—the dark green dots—come from three sources. I start with WSDOT’s biennial Ramp and Roadway Report. Then, to add in the missing years I factor in data from the Annual Traffic Report series and Seattle’s Traffic Flow Data. The blue trend line is just the basic linear regression of the blue dots, as calculated by Excel.

The light orange line is based on a projection that dates back to 1996, which was mentioned in WSDOT’s 1999 Trans-Lake Washington Study. Since that report is only available on CD-ROM, but not online, I’ll quote the report directly:

Under the No Action solution set, Trans-Lake travel [on SR-522, SR-520, and I-90] is expected to increase by about 168,000 daily person-trips…in the year 2020…Because capacity is limited on SR 520, only about 20,000 additional vehicle…trips are expected there.

(If current trends hold, the projections of 20,000 additional vehicle trips will be off by about 20,000 additional vehicle trips.)

The green line is from the 2002 Trans-Lake Washington Project report, also available on CD-ROM, which projected that traffic under the “No-Action Alternative” would grow by 20 percent through 2030.

The dark orange line—127,400 cars by 2030—is from the recently released Final Environmental Impact Statement for the SR-520 bridge replacement project. It’s based on the projections described in part 1 of the “transportation discipline report” (see Exhibit 5-3 on p. 92 of the pdf, and the projections for SR-520 at Midspan under the 2030 No Build Alternative: 127,400 vehicles by 2030).

I could have included another projection from the 2006 Draft Environmental Impact Statement—127,860 vehicles per day by 2030, as claimed in Exhibit 10-8 in Appendix R part 6. But it was getting hard to fit all the wrongness on a single chart.

Now, I know that total traffic volumes aren’t the only traffic trends worth paying attention to. The traffic models make projections about peak-hour delays as well, which are probably what commuters care most about. But given that the models have proven so stubbornly and preposterously wrong about traffic volume trends, it’s hard to believe that they have much of value to say about future traffic delays.

[Thanks to Jake Kennon and Pam MacRae for help with the numbers!]

Cheryl dos Remedios

This is WSDOT’s reality: a 12-lane highway cutting through the Arboretum’s wetlands, from Montlake to Foster Island.

It breaks down like this: 3 lanes of traffic + 2 lanes of ramps + 1 lane of shoulder x 2 = 12.

I’m not sure how to reconcile the traffic data above with what I know about this project, so Clark, I could use your help.

During peak hours, my understanding is that I-5 cannot handle the increased traffic of a 6-lane bridge, so WSDOT is planning 4 lanes of ramps in the Arboretum’s wetlands to store cars as they try to merge onto I-5. This will prevent back-ups into the Montlake neighborhood and at the I-5 interchange itself.

Word on the street is that the “ramps will be removed from the Arboretum,” but this just isn’t true. It is true that the existing ramps that peel off and connect to Lake Washington Boulevard (LWB) will be eliminated, yet the negative impacts to the Arboretum increase. Here’s how: WSDOT is planning for the new ramps placed in the wetlands to connect back into LWB, just at a point that is technically outside of the Arboretum. WSDOT expects highway traffic to increase through the heart of the Arboretum along LWB.

Under current federal regulations, we should not be able to bisect a historic park with highway traffic at all, but WSDOT leans on the site’s “pre-existing conditions.”

Watch this video and please pay especially close attention to 3:40 – 3:50 and 4:14 – 4:30: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCV7COUSs0k

And next time you are on I-5, count the lanes and imagine that swath pavement cutting through the Arboretum. Imagine kayaking in the Arboretum with 12 lanes of highway overhead.

12 lanes of highway to store idling cars in Seattle’s most pristine wetlands. . . this is WSDOT’s reality? This is insane.

Randy

Bottom line, Seattle and WSDOT have no clue what they’re doing. If you think effective traffic management is creating HOV lanes in on ramps and going from 6 lanes to 2 lanes downtown is effective, you’re high. Even the express lanes aren’t express any more. When it takes 45 minutes to get across either the 90 or 520 bridge, it is obvious there is no planning. There was no plan for traffic management in Seattle and I’ve lived in much larger cities where traffic wasn’t half as aggravating. Add to the poor planning drivers who have NO clue how to drive and it all becomes a pile of mess.

I challenge anyone to figure out how to get the appropriate amount of traffic across any highway in this town all the while focusing on the environment. It can’t be both ways. We can’t expect to fix traffic issues and keep ALL environmentalists happy. It seems to me all the idling I do on the highway is worse for the environment.

archie

Congestion pricing.

Clark Williams-Derry

bingo.

G-Man (Type E)

No one will pay for congestion. They get plenty of it for free already.

How about “De-congestion price” or “free-flowing lanes charge” or “guaranteed travel time price” or anything else that accurately conveys that concept? How about instead of saying we want to toll or price a highway, we say we would like to sell commuters access to guaranteed free-flowing lanes. Focus on the benefit, and to support projects like pricing I-5 express lanes, let’s trot out the evidence from other cities that this actually improves traffic flow in adjacent non-tolled lanes as well.

Randy,

If we add an extra lane you will pay more taxes or tolls for 30 years on an improvement that alleviates your idling for maybe 5 years max. After that congestion would be back to today’s levels but with a higher cost to clean air, water and land. If we used variable tolls you would pay daily at your own discretion. A sign could say – this lane $5 / 15 minutes, that lane free / 30 minutes and you make your choice. How’s that for freedom? (for the 520, your free alternative would be I-90 and any smartphone now can tell you the time difference). Variable tolls that assure travel time also mean faster, more reliable buses – means more people using them – means less competition on the road from other drivers – means lower tolls and a faster commute for you – a virtuous circle! You’re wrong to think there isn’t a solution – there is always a path to progress if we are bold enough to act without fear, grounded in solid evidence of the real relationships that shape our world.

Danny

WSDOT already has some congestion pricing in place, why not bring it to Seattle?

http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/NR/rdonlyres/A43B9DD4-4228-482E-BF82-CEE31B315A0E/69595/2ndAnnualReport_167HOTLanes2.pdf

Paul Birkeland

Well, Clark, as Kurt Vonnegut might have said, “Hi ho!”

I actually derive some hope here. If in the face of explosive growth in Redmond and at Microsoft over the last 16 years, and in the face of such moderate gas prices and overall population growth we still managed to reduce traffic volume, it makes me believe that there is some fundamental dynamic driving us (no pun intended) to drive less. Not sure what it is, but its impact is a positive one, and perhaps unstoppable.

As far as the DOT models go, I would wonder exactly how they were built. Typically models like that are not just linear extrapolations from the past. They are usually ‘build ups’ of various economic projections – this much freight traffic, this much commercial traffic, this much commuter traffic, etc. You add them up and get your total.

So what in the DOT models didn’t happen, and why? Are we telecommuting more? Is freight going somewhere else? Is commercial activity developing in a different geographic pattern than projected?

Answers like that would substantiate the fallacy of the models, and perhaps lead to improvements that might yield more accurate estimates of future traffic.

Nice work here, Clark.

Paul

Clark Williams-Derry

Paul – I don’t pretend to be an expert on the models. But the PSRC travel model is basically a “4 step” model. Step 1 is to estimate demand for trips, based on projections of population, income, employment, fuel costs, and other economic/demographic factors. Step 2 is figure out where the trips go, based on a “gravity model” of the attractiveness of various destinations. Step 3 is to assign mode, and step 4 assigns routes.

My working hypothesis — which is really no more than a guess — is that step 1 isn’t working well. Despite income & growth, we’re not generating as many trips per person as we used to. I agree, that’s a good thing overall, but some of the big causes aren’t all good: high gas prices that cause economic hardship to families; lower-than-anticipated employment, particularly in certain demographics; etc. Regardless of the reasons, total VMT trends aren’t moving the way people were anticipating they would. Things have changed. Will they change back? Who knows!!

But I also sense that there’s something broken in Step 2. That is, the models overestimate the “attractiveness” of crossing 520. The models suggest that people should be lining up earlier & earlier to get to jobs & stores on the other side of the lake. Maybe they are — but if so, it’s not reflected in total traffic volumes. And it seems to me that the flaws with the trip distribution step of the model surfaced long before the mid 2000’s, when gas prices started to rise in earnest.

DJStroky

Step 4 is where the bulk of the error comes from in my opinion. Most models won’t immediately stop assigning traffic onto a road if the volume/capacity ratio goes over 1.

I think the real reason traffic hasn’t grown on 520 is that it has been completely at capacity for the last 10 years or more. And not just 520, wherever there are roads that are completely clogged no growth ought to be expected.

Carl

Then when we create new capacity on 520, there will be induced demand to drive it since it will be easier.

I wonder whether DOT has modeled the effects of tolling, or whether people understand that it is $7 round trip in peak times

Clark Williams-Derry

Carl –

I agree. I think that it’s likely that if the bridge were widened and had no tolls, it would quickly get saturated with additional traffic.

Eric Doherty

If I remember correctly it was General Motors that funded the development of 4-step traffic models.

Someone less polite than me might say that computer assisted BS is still BS. Good thing I am so polite and would never say such things.

Clark Williams-Derry

DJStoky –

Good point. Maybe a synthesis: the results of step 4 don’t get fed back into step 2. When roads get full (step 4) the increased travel times aren’t properly factored back into the “attractiveness” of the affected destinations (step 2).

Levin Nock

What will it take for the transportation planning industry to update the industry standard of modeling to include things like feedback loops, verification and calibration? A masters student would be flunked for a thesis with such woefully inadequate modeling, yet we continue to invest billions of dollars based on this “guidance”.

Levin Nock

Based on Rob’s message below, it sounds like the actual models are quite sophisticated, but the results are usually labeled incorrectly. Has anybody seen a traffic forecast chart labeled “Number of trips that people wish they could take, in the absence of any congestion or congestion pricing”? I’ve never seen it. The word “forecast” suggests that the forecaster expects something to actually happen–not that they expect people to wish for something that will never happen.

Erin

As you calculate the width of the new Floating Bridge (Stage 1, said to be funded) and the new West Approach Bridge (Stage 2, unfunded), note the additional 14-foot lane for the bicycle/pedestrian path, 10 foot shoulders, 11-foot general purpose lanes, 12-foot HOV lanes, all capable of being restriped for more lanes, and a gap ranging from 35 to 40 or so feet reserved for Light Rail between the “North Bridge” and the “South Bridge.” WSDOT’s Request for Proposals (RFP) is for a “Future Six-Lanes Plus Two HCT Configuration, not for a Four-Lanes Plus Two HOV Lanes to be converted to HCT later. See the RFP on WSDOT’s site.

Rob

This is a good observation, but not difficult to explain in modeling terms. Transportation models (all of them, not just WSDOT’s, which is also the PSRC’s) attempt to model demand, not throughput. In real life, traffic on both I-90 and SR 520 has been constrained by capacity for a long time. Eastbound and westbound traffic is about equal, not because there’s equal demand each way, but because capacity limits have been reached in both directions. So yes, traffic’s not likely to grow a lot more with the current facility – but that doesn’t mean there aren’t lots of people who would cross the lake if it weren’t so onerous.

There is a volume-delay curve in the model that attempts to show how traffic will slow if demand exceeds capacity, but it’s not perfect. When the model is calibrated to current conditions, it’s tweaked until it produces results that match current volumes, so it’s forced to show demand equal to throughput. But as population and employment grow in the future, the model will try to add trips incrementally throughout the network, so it’s likely to show some growth. This effect is most pronounced for cross-lake trips, since there are no alternative routes to the two cross-lake highways. In other places the model is more successful finding other routes to move the demand to.

Demand has also been slowing recently because of the prolonged recession. The most effective transportation demand management strategy remains to wreck the economy – but it’s not clear that’s a good strategy to plan for over the longer term. Also, if 520 is widened, even for HOV, there will be more throughput because (1) there is a ton of latent demand there, and (2) in addition to increased capacity, just having shoulders will stop breakdowns and wrecks to bring traffic to a halt.

I think the take-away from this should be that model results should always be accompanied with a primer on modeling limitations. They aren’t perfect, and every modeler will be honest about that. In real life traffic probably won’t increase if the bridge isn’t expanded, and it will get only marginally more congested. But more people will *wish* they could cross the lake than will be able to, and whether it’s a good or bad thing to accommodate them is a policy choice, not a technical issue.

Clark Williams-Derry

I totally agree with you about the limits of models — and that responsible modelers are always careful to respect those limits. If only we could get everyone to read a treatise on modeling limits (along with examples of obvious failure) before they were even allowed to contemplate model outputs, the world might be a better place.

But unfortunately, I’d argue that’s not even close to the role that modeling plays in the public debate. Instead, politicians and project boosters treat model outputs as near-certain predictions of perpetual gridlock. In fact, I’d argue that the models underpin & prop up a broad and deeply flawed consensus about how travel habits change over time.

Which brings up a question — should we even bother to use models in a case like 520? The current crop of models is simply useless at predicting actual traffic trends, and the near-universal misinterpretation of model outputs deeply distorts the debate.

If politicians had the courage to say “we are building a wider bridge because we think that a lot of people would like to drive on it,” we’d have an honest debate about the costs & benefits. But instead they say “ZOMG you’ll all be stuck in traffic armageddon!!! I know it’s true because….models!” And we wind up building more megaprojects than we need, paid for by people who don’t see much benefit from them.

Levin Nock

It appears that the calibration process fudges the model, to pretend that the model is related to reality. Since 1996 and before, there have been plenty of people wishing they could travel more on 520: even in 1996, 2002 and 2011 when WSDOT pretended there were none. Since WSDOT wants to model wishes, rather than actual traffic, they should draw a horizontal line up around 200,000 or 300,000 or somewhere above, sloping gently upward, to make crystal clear that the only way to address this demand is with light rail and commuter rail, or possibly complete networks of free-flowing bus lanes and cycle paths.

Jessica

Clark, do you have data (and free time) to add actual traffic volumes from earlier years? I’d like to see when the downward trend started and whether the slopes of WSDOT’s estimates have ever matched actual traffic growth. That is, has traffic ever grown that fast? If so, how long ago?

Thanks for this post–it’s exactly why I donate to Sightline every month!

Jesse

I know we need some increased capacity, but I’d rather that errored on the side of shoulders and HOV lanes. Those by themselves would double the size of 520 and probably greatly increase throughput.

But as I love to quote an Orlando traffic engineer: “Widening roads to solve traffic congestion is like loosening your belt to cure obesity.”

Levin Nock

Here’s a corollary:

“Forecasting Seattle traffic while assuming there’s no congestion is like forecasting Seattle weather while assuming there’s no rain.”

It’s not very useful, and it just might be misleading.

Southender

People have commented that the translake connections are capacity constrained, which may have some merit with 520, though volumes and hours of delay are decreasing. Latent demand would likely absorb the freed up capacity if that were true.

Also, the I-90 bridge was forcast to have significant increases in traffic volume, which it has the capacity to sustain. Likewise, the models have significantly overestimated the ADT and peak-hour volumes there as well.

With the trends begining a long-term reversal in 1996, especially when compared to regional population growth, it’s also hard to argue that the effect of either of the two recessions that happenend over that time-period is solely or even largely responsible for the decline.

Bryan

I would think it would be readily apparent to everybody (but apparently it is not) that the reason traffic has been trending down is because natural changes to the structure of growth occured due to the restrction that seattle traffic placed upon that growth.

In most other cities you would see the core grow as whole local economy grew. Financial, shopping, etc would typically grow in the core as the outer businesses grew. So compare those traffic projects to Bellevue growth during that time. The growth of Bellevue could largely be attributed to the utter lack of access to downtown Seattle provided by the capacity of 520 and 90 (as well as horrible I-5 connections at their western termination).

Ralphus

Using a linear regression to predict future traffic volumes from historic ones is a deeply flawed methodology. In fact, it is the almost assuredly the same methodology WSDOT used to generate the inaccurate growth predictions you’re discussing (although perhaps using a longer time frame or area-wide figures). Maybe volumes really will not display much growth, as you predict, but a linear regression is not much proof of that.

Also, I thought clarification on the actual base-data in your graph might be pertinent. WSDOT’s Ramp and Roadway Report provides Average Weekday Traffic (AWDT) volumes reflecting Tuesday through Thursday. This data is almost exclusively drawn from electronics in the roadway that are primarily purposed for real-time traffic management. However, most statistics in the Annual Traffic Report are Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) volumes reflecting Sunday through Saturday. This data is drawn from the WSDOT HQ traffic counting program, which is designed to collect data for planning purposes. Because weekday volumes are almost always higher than Sunday through Saturday averages, the statistics found in these two sources are not comparable. The only exception would be for the 150 or so permanent traffic recorders for which data is provided in the Annual Traffic Report. For these recorders (which are the most accurate that WSDOT has at its disposal) both AADTs and AWDTs are provided. One of these is on the 520 bridge, and is listed in the Annual Traffic Report as recorder D10. The AWDTs for this recorder are listed below, although the older ones need to be requested from WSDOT since AWDTs were not carried in the report until 2001.

2009 : 106599

2008 : 105994

2007 : 107040

2006 : 108237

2005 : 111035

2004 : 110293

2003 : 110524

2002 : 109719

2001 : 110541

2000 : 111786

1998 : 112671

1997 : 111281

1996 : 108719

1995 : 110094

Clark Williams-Derry

Ralphus–

It seems like you think that the dark green line is a prediction. This line is nothing more than a regression, describing the past trends. I’m not offering my own predictions here — only an observation that past predictions haven’t held up.

Ron Richings

I don’t have a problem with your basic critique, but the graph that you used is really a bit misleading by virtue of eliminating the scale below 90,000. If you presented the full graph down to the zero base what now looks like a fairly vast discrepancy would instead look, correctly, like a relatively small proportion of complete traffic estimates.

I know, I know, people often use only sections of graphs to help illustrate their points, but it is really bad practise when used to give an overall impression for general public consumption.

Rhys Roth

On the other hand, what really matters in terms of rationalizing expansion of the bridge is how much ADDITIONAL traffic is expected when. From that standpoint, Clark’s graph focuses exactly on the essential information and does put it in proper perspective.

Stu Ramsey

Wow, it’s not everyday you see an extened discussion of the weaknesses of transportation models! I used to make a comfortable living running this exact type of model, and I agree with many of the concerns raised. The models inherently assume that people will make the same decisions in the future that they did in the past. And that all trips will be completed, no matter how congested the network gets.

By and large, modellers spend a lot of time agonizing over small modelling questions (will this road have a capacity of 600 or 700 vehicles per hour?) and ignoring the larger ones (will there be carbon pricing? will the built environment encourage more active modes?).

For the truly dedicated student, I discuss these questions on my web site. You can go to http://www.transportplanet.ca/presentations.htm and scroll down slightly to the various links for “Of Mice and Elephants”. Your choice of PowerPoint file, 40-minute video, or peer-reviewed technical (but still readable) article.

Among other things, I concur with Clark’s statement that there are times when we would be better off to not run the model at all.

political_incorrectness

They are trying to pull a George Massey tunnel with 520. 6 lanes to 2 never works and ends up forming one giant queue. Also, this might have negative consequences with I-5 soutbound which suffers from chronic congestion from Lake City Way to the Ship Canal Bridge after the express lanes change over. Realisitcally, I-5 will probably need to be rebuilt for a 4x2x2x4 configuration in order to get the best throughput. It will be damn expensive but I think that is probably the best way to do it if I-5 is rebuilt. If they are expecting Eastside growth, they should probably allow transit expansion across the bridge. I find it disturbing that some believe the express lanes on I-90 provide valuable capacity when they are merged at the very end and only cause congestion later.

Dave

I think the heart of the matter here is a questions of how one manages the uncertainty of the future. Forecasts are not predictions of the futrue so much as they are risk management tools.

I completely agree that the trendline forecasts typically assume future trends will basically match the past. I’m working on the update to the GMA Transportation Element guidebook right now and one of the main new themes I’m trying to devleop is how to manage uncertainty. Many have observed that our ability to predict the futrue based on the past is significantly less now that it was 20 years ago. If any of you care to visit the project webe site, I’d be very interest in your comments. We are releasing preliminary drafts chapter-by-chapter, with a final draft coming after that.

Barb Chamberlain

Take a look at the new modeling being developed at PSRC. I just sat through a presentation on it and the direction sounds as if it will get at more information on what people really DO, which is not just home-to-work trips and back again at the end of the day.

It still won’t adjust quickly to new ways of thinking about how to get somewhere. As someone noted above, those history-based assumptions are breaking down now faster than ever before.

Doug McClanahan

Care to revisit your criticism now?