Grant County, Washington has no shortage of food. There’s plenty of land devoted to growing wheat, potatoes, apples, mint, grapes, and peas in a county that ranked second in the state for agricultural sales in 2007.

Grant County, Washington has no shortage of food. There’s plenty of land devoted to growing wheat, potatoes, apples, mint, grapes, and peas in a county that ranked second in the state for agricultural sales in 2007.

But, according to the new USDA Food Desert Locator database and mapping program, nearly one in four county residents lives in a food desert with limited access to affordable and nutritious food. Roughly half of those people are low income.

When it comes to addressing obesity and hunger, food deserts are only one part of a much more complicated picture. They may be a problem for a relatively small percentage of households, and it’s easy to overstate their importance. But for someone living in one and having trouble meeting such a basic need as eating, it’s probably a big deal. At least in the US Northwest, new maps show a significant number of people who may lack easy access to affordable and healthy food live in rural areas, including places that grow huge quantities of food.

The new federal Food Desert Locator identifies census tracts that the USDA considers food deserts, which means the population has lower than average income and a significant number of residents (either 20 percent or 500 total) have low access to a large grocery store or supermarket. In urban areas, that means living more than a mile away from the grocery. In rural areas, the threshold is 10 miles.

In each food desert, you can zoom in on street boundaries and see how many low-income residents, kids, households without cars, and seniors live in that particular neighborhood.

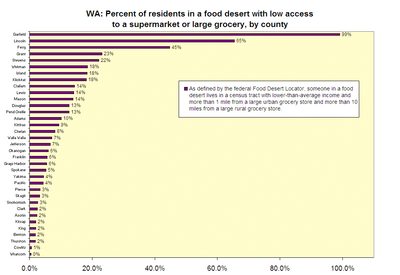

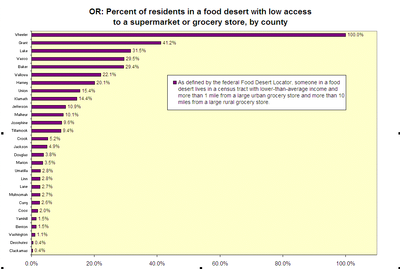

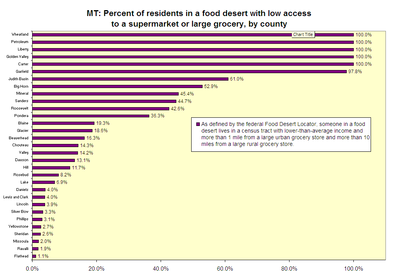

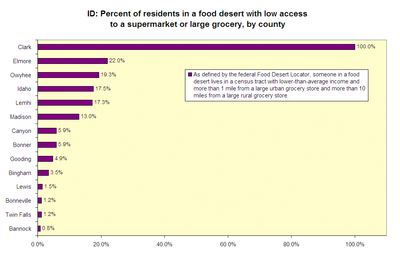

You can certainly argue about whether the USDA food desert definition has any real meaning, and I get into the considerable limitations of the data below. But I was still a little curious about what the maps showed. So here are some charts ranking which counties in Northwest states (Washington, Oregon, Montana and Idaho) have the highest percentage of residents living in the USDA’s definition of a food desert:

Click here for larger version of Washington chart.

Click here for larger version of Oregon chart.

Click here for larger version of Montana chart.

Click here for larger version of Idaho chart.

Here are some other factoids from the Food Desert Locator data:

- In Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana, there were 450,000 people living in the USDA food desert tracts with low access to a large grocery store, or about 4 percent of the population. Roughly 195,000 were low income.

- Dense urban areas like Portland and Seattle don’t have a lot of food deserts (with the exception of some portions of North Portland, West Seattle and south King County suburbs). In those metropolitan areas, neighborhoods near airports and heavy industry look more likely to be considered a food desert.

- Across the region, nearly 40 percent of people living in food deserts with low access to large groceries lived in rural areas.

- There were 11,749 car-less housing units in the food desert tracts.

- In Washington, only four counties (San Juan, Columbia, Wahkiakum and Skamania) had no food deserts at all.

- In Oregon, seven counties (Clatsop, Columbia, Gilliam, Hood River, Morrow, Polk and Sheridan) had no food deserts.

- Idaho and Montana each had dozens of counties without any food deserts (puzzling, given just how rural those states are.)

Now, if your county or neighborhood is colored pink on the food desert map, there are plenty of reasons why things might look different on the ground. For instance, Ashland, OR residents were surprised (and irritated) to learn that part of their city was labeled as a food desert.

You can find more detail about the USDA methodology here, but here’s the gist. To qualify as a food desert, a census tract has to have at least a 20 percent poverty rate or have less than median income. Then it has to have a substantial share of residents with low access to a supermarket or large grocery store, which is defined as food stores with at least $2 million in sales that contain all the major food departments found in a traditional supermarket.

So a rural area with roadside markets or a general store or community gardens could still show up as a food desert in this analysis, which doesn’t acknowledge that there are plenty of other places where people can get nutritious food besides a Safeway. A quick look at the census tract in Ashland suggests that because it’s long and skinny, a number of people might live more than a mile away from the nearest grocery store or food co-op, even though there are at least five within the city’s borders.

The food desert definition also fails to address how easy it is to get to a grocery store on public transportation. If you don’t have a car, living two miles away from a grocery store with a bus line outside your door is quite different than walking or borrowing a car to travel two miles on rural roads.

So the food desert maps aren’t really useful as an exercise in labeling or drawing precise boundaries, but they may still have some value. As Ashland Mayor John Stromberg told the Daily Tidings, he’s inclined to be “wary when presented with an analysis based purely on statistics put together by someone possibly 3,000 miles away.” But he also acknowledges that the numbers might inspire a more fruitful discussion.

They raise an important question, which is ‘Do we know who within our community is having difficulty getting the essentials of life, that is food, shelter, medical care?’ We only have

indirect information at best and, in these times, people can easily fall through the cracks.

Notes on sources: Data used in the county-by-county ranking was downloaded from the Food Desert Locator. For each county, the number of people living in “food desert” Census tracts and identified as having “low access to a large grocery store or supermarket” was divided by the county’s total population. The Food Desert locator does not count or include people who have low access to grocery stores but live in Census tracts that do not meet the USDA threshold for a food desert.

Grain elevator photo courtesy of flickr user afiler under a Creative Commons license.

Comments are closed.