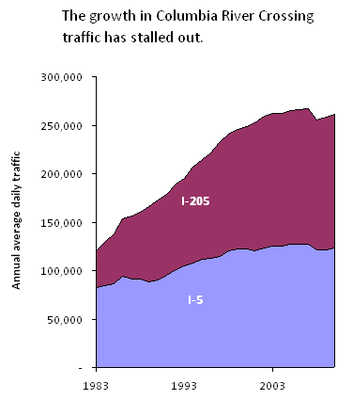

Continuing my obsession with the ever-mounting evidence that traffic volumes are growing much, much slower than transportation planners had expected, I present to you: Traffic volumes on the I-5 and I-205 bridges across the Columbia River, with data courtesy of the Washington State Department of Transportation’s Annual Traffic Report series.

In case it’s not obvious from the chart, traffic on the two highways combined was a wee bit lower in 2010 than it was in 2003. Much of that decline was due to the sharp drop-off in 2008, when gas prices were high and the economy tanked.

But if you look even closer at the numbers, you’ll see something else: in about 2000, the growth in traffic over the Columbia started to stall out. Before then, traffic grew by an average of about 5 percent per year. Since the new millennium, though, annual traffic growth has averaged about 0.5 percent. Even if you exclude the declines in 2008, traffic grew at only about 1 percent per year starting in 2000.

That’s for the two highway bridges together. If you look just at the I-5 span across the Columbia, traffic volumes in 2010 were just a hair above what they were in 1999. That’s more than a decade with essentially no growth in traffic!!

Of course, even slow growth can add up, if you wait long enough. Still, the oft-cited rational for the Columbia River Crossing megaproject—an expansion of the I-5 span that’s projected to cost between $3.2 billion and $3.6 billion—is that traffic is growing so rapidly and so inexorably, that we have to spend exorbitantly to prevent congestion from miring the Portland metro area in perpetual gridlock.

But the projections of rapid traffic growth come primarily from transportation models. And those models essentially have rapid traffic growth built in as core assumptions—which means that rapid traffic growth isn’t so much a conclusion of these models as a premise.

Up through the 1990s, that premise was more or less true: year after year, you could count on steady increases in traffic volumes across the Columbia. But for the last decade or so, the world just hasn’t worked that way. And as a result, the idea that we have to build more and more lanes to accommodate the crush of new traffic is looking shakier with every passing year.

constraints

A flat growth of driving demand is not the only possible explanation for a flat growth of cars crossing the Columbia River.Other possible explanations – during peak driving times, maybe the bridges are at maximum capacity, and drivers are either choosing to wait for longer periods of time to cross (thereby contributing to greater traffic congestion elsewhere in Portland), or, they are decreasing their personal reasons to cross the bridge and sacrificing their mobility below an optimum level.

John Niles

This is a very interesting data set. Are we perhaps seeing a case of “don’t build it and they won’t come” on this infrastructure segment? Lousy congestion on the two bridges over the river during peak has perhaps been enough to cause people to rearrange their jobs and housing and shopping so they don’t cross the bridges so much. While writing this note “Constraints” has made this same point in a previous comment.Would be good for Sightline to explore traffic volumes where we know there has been strong growth in housing and jobs. How about to and through Snohomish County? What’s the story up there? I’ve noticed a big expansion of HOV lanes through Everett in recent years, and the northbound I-5 exits at Smokey Point and Stanwood have been expanded. Have volumes stayed up since 2000? That might be “build it and they’ll come.” Has been true of housing.

Craig Beebe

Even if John’s assertion is accurate—that people are rearranging their jobs, housing, and shopping to avoid crossing the bridges—would that be a bad outcome? Americans have come to assume that free-flowing freeway infrastructure should just be a “given,” but reductions (or even just stagnation) in the number of cars crossing the Columbia translates into that much less air pollution as they pass through North Portland.Clearly we need to move freight more efficiently through the region, but I remain unconvinced that the traffic volumes (actual and likely) justify the size and cost of the CRC as it currently is envisioned.

Jim Howell

The CRC Project as proposed will induce the traffic that is projected, create huge traffic backups on other parts of the Portland freeway system, encourage further sprawl in Clark Count and create more oil use,air pollution and greenhouse gases.Please Google “CRC A boatload of questions” and “CRC Common sense alternative” animated by Spencer Boomhower.

Clark Williams-Derry

Costraints:I agree with you. There are all sorts of reasons why traffic might have leveled out. Reaching max peak hour capacity is one of them; so adding capacity might induce new traffic by releasing pent up demand for peak-hour travel.Yet at the same time gas prices, demographics, and other trends appear to be reducing the overall appetite for car travel. It’s not just the CRC, it’s happening in lots of ways throughout the Northwest states and British Columbia.Still, the point I’m really trying to make is that the CRC traffic projections—see, e.g., figure 4.1 in the traffic technical report to the CRC EIS don’t match up with reality. The traffic technical report’s models predict that I-5 volumes will grow almost 40% by 2030. Yet traffic on I-5 has remained roughly flat for a full decade. That suggests that the EIS methods—and traffic models generally—are doing something wrong. They’re projecting massive gridlock, based on traffic volumes that don’t seem to be showing up.

Stacey W-H

Is “Constraints” arguing that not building the CRC would force people to make sub-optimal transportation choices? That we should build endlessly so no driver is ever restricted about where or when they want to drive? Perhaps there is a socialist engineering plot to infringe on the driver’s personal freedom to travel unimpeded? I would argue that the cars have had it their way for most of a century and the result has been disastrous for pocketbooks and the environment. The folks who would rather live in a walkable community, pocket their gas money and take mass transit have lived sub-optimally for decades. We have no idea how pent up that demand is, but we know we are close to providing an ideal world for cars. This argument has been made many times over the years but it is worth repeating again: we have a limited amount of time and resources to make the transition to a low-carbon future. Massive transportation projects damage our ability to respond to the climate crisis by 1) building long-lived infrastructure that increases rather than decreases emissions, 2) consuming exorbitant public resources which should be focused like a laser on the low-carbon transition. If those reasons aren’t enough, think of how diversifying our transportation system enhances our ability to stand tall in the face of uncertain global energy markets, lessens our contributions to foreign dictatorships, reduces the need to spend billions of dollars and thousands of lives on military activity designed to protect our inefficient transportation system, reduces the dollars we send out of the region and out of the country (increasing our foreign debt), supports a broader range of safer and more active lifestyle choices, frees up land for other uses—the list goes on and on. The CRC project presents a fabulous opportunity to build the future we want, rather than the one our past has been telling us does not work.

Constraints

Is “Constraints” arguing that not building the CRC would force people to make sub-optimal transportation choices?No, I’m not saying that’s definite. I’m saying it is possible.That we should build endlessly so no driver is ever restricted about where or when they want to drive?No, I don’t recall saying that.Perhaps there is a socialist engineering plot to infringe on the driver’s personal freedom to travel unimpeded?Wow. No, I have not made any such claim above.My agenda in posting the first comment was that I enjoy analyzing causal relationships in a logical manner. Clark wrote back, nice exchange. Clark’s belief is that the flat growth of bridge traffic is an indicator of flat growth of traffic demand. I pointed out it’s also a possible indicator of other causes. Clark pointed out other possible indicators that further reinforce traffic demand actually possibly being flat. It’s interesting.From what I can tell, your opinions are different. You would prefer to create a reality where people would have to adapt to a less car-friendly world, in the name of transitioning to a low(er)-carbon future. Even if the growth of traffic demand would otherwise increase, you would prefer to not widen vehicular bridges. Is this fair to say?Let me ask you an unfair question. Are you in favor of demolishing all the vehicular bridges into and out of Portland, and creating tolls or gates for all land roads into Portland? I would assume not.But I would submit that anyone who isn’t in favor of creating gated communities out of cities accepts that there is a level of mobility in and out of cities that is desirable and required. The question is how to define that level of mobility.I think it is fair to say that if traffic demand increases and capacity doesn’t, then overall mobility will decrease over time. Maybe ten years ago it was possible to live in Vancouver and work in Portland, get off at 5 and be home by 6. And maybe now that is not possible, and family life suffers, or they can’t take a job in Portland, or they move away, or they move to Portland with higher expenses. And maybe that’s an acceptable loss, and maybe it isn’t.The question is measuring at what point that decreased mobility becomes unacceptable, and how much right we have to decide that for other individual people. That’s where the a lot of the opinions diverge.

Constraints

I should also point out that if you believe that building a wider bridge will result in greater traffic (a spike of growth), then it means that pent-up traffic demand actually has happened. If Clark believes that there is no such pent-up traffic demand, then building the wider bridge won’t lead to a measurable increase in traffic flow across the bridge.I understand that this depends on how you define demand. Some may feel they “need” the increased mobility, whereas others may just take advantage of it while they don’t now. (A wider bridge could also attract others to move here that prefer that level of mobility, leading to a homogenization of culture.) But the point is that if it happens, it means that there has been a growing demand that is currently “hidden”, even if it is at a slow rate.And what is important about that is that if it’s been growing in the past, it will continue growing in the future. And as mentioned above, it will decrease mobility. And the question is at what point does that slowly degraded mobility start to hurt a population too much, and how would one measure that.

Clark Williams-Derry

Constraints:Just to be clear: my gut instinct is that if the CRC is widened and not tolled, and if speeds do increase as projected, traffic volumes on I-5 across the Columbia WILL increase. And I think it’s very likely that total, combined traffic volumes on I-5 and I-205 will increase. I think that will happen due to a combination of pent-up demand (that is, trips that existing residents would like to take if only they could get across the Columbia faster) and because of induced demand (people & businesses who gradually shift destinations, or choose to locate in different places, because of the faster travel speeds offered by a wider highway).However, I think that tolling throws all this into a cocked hat. With high tolls on I-5, you could see significant diversion to I-205, or even reductions in travel demand. Yet just as the cost of the tolls isn’t known now, the effects of CRC tolling are unknowable.But also, my gut instinct is also that if the CRC is not widened, traffic volumes on I-5 across the Columbia won’t increase nearly as much as the traffic models predict. This is based on the observation that traffic volumes on I-5 haven’t budged since 1999, and the fact that driving costs (including congestion, gas, etc.) and demographic changes appear to be shifting the demand curve for driving—though I have no idea if those costs will remain high or if the demographic shifts will continue.In my mind, the question of whether the CRC is a “good” public investment is an entirely separate matter. I think that’s the question you discuss in your second response, above—and I agree that there are pluses and minuses to faster peak-hour travel across the CRC. People have different opinions.My hunch—or perhaps my bias, you choose!—is that the minuses to widening the CRC probably outweigh the pluses. This is based on 2 facts: first, the CRC costs so much more than users are willing to pay for it; and second, there are big externalities to driving (shipping money out of the region to pay for oil & cars, committing greater Portland to dependence on an unreliable and diminishing natural resource, traffic accidents, greenhouse gas emissions, other pollution, etc.) that aren’t fully borne by users. Users aren’t willing to pay for cost of the bridge expansion itself—let alone the externalities. So why subsidize those trips? (I say this, fully recognizing that the light rail expansion should probably be judged with similar criteria, and that there are positive externalities as well as negative ones to faster cross-Columbia trips.)

Steve Erickson

I think this is just one manifestation of a larger phenomenon, namely, that the population growth-growth-growth model is just not reflecting reality anymore.The recently released census data for Island County (where I am) reflects this. Viewed in decadal (10 year) increments since 1970, the rate of increase of population has dropped by about 50% in every succeeding decade. That is, the rate of increase from 1980-1990 was about half what it was from 1970-1980; 1990-2000 was about half of 1980-1990; etc. Note that this consistent trend includes the boom years of the 80s, 90s, and 00s. If the trend holds, by the late teens there will be essentially zero population increase occurring in Island County. In fact, Whidey Island actually lost population (about 2,000 people or approximately 2.5%) between 2000 and 2010. This is extremely encouraging and suggests that at the local level in at least some places population stability or even decrease towards sustainable levels may be in the offing. Of course, this is anathema to the boomers, but the physical reality is that the sooner we move to a steady-state economy, including in population, the sooner we’ll get to a situation of sustainability in terms of consumption of resources and excretion of waste. -Steve EricksonWhidbey Environmental Action Network

Todd Litman

Thanks Clark. This is one more bit of evidence that automobile travel demand is stabilizing or declining, what British Transport Guru Phil Goodwin calls “peak car.” This has important implications for transport policy and investment decisions:* Traffic congestion will be less of a problem.* The justification for roadway expansion is declining.* The justification for other types of transport improvements will increase. * Road tolls will provide less revenue than projected.Many recent toll road projects have experience far less traffic and revenue than what was projected, leading to revenue shortfalls and bankruptcies, including the Clem Jones Tunnel project in Brisbane, Australia and the South Bay Expressway (SR 125) in San Diego County, California. Here in British Columbia, the new Golden Ears Bridge, is experiencing far less traffic than projected, leading TransLink to reduce the toll from $2.80 to $1.95 during off-peak times in order to attract more motorists.================For more information see:Phil Goodwin (2011), “Peak Car: Evidence Indicates That Private Car Use May Have Peaked And Be On The Decline,” RUDI, Urban Intelligence Network (www.rudi.net); at http://www.rudi.net/node/22123. Todd Litman (2006), “The Future Isn’t What It Used To Be: Changing Trends And Their Implications For Transport Planning,” Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at http://www.vtpi.org/future.pdf; originally published as “Changing Travel Demand: Implications for Transport Planning,” ITE Journal, Vol. 76, No. 9, (www.ite.org), September, pp. 27-33.David Metz (2010), “Saturation of Demand for Daily Travel,” Transport Reviews, Vol. 30, Is. 5, pp. 659—674 (http://tris.trb.org/view.aspx?id=933522); summary at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/news-articles/1006/10060306 and http://www.eutransportghg2050.eu/cms/assets/Metz-Brussels-2-10.pdf. Adam Millard-Ball and Lee Schipper (2010), “Are We Reaching Peak Travel? Trends in Passenger Transport in Eight Industrialized Countries,” Transport Reviews, Vol. 30 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2010.518291); previous version at http://www.stanford.edu/~adammb/Publications/Millard-Ball%20Schipper%202010%20Peak%20travel.pdf. Stuart Ramsey and David Hughes (2009), “The Challenge of the Oracle: Optimizing Transportation Infrastructure in a Changing World,” ITE Journal, Vo. 79, No. 2 (www.ite.org), pp. 69-73. http://www.transportplanet.ca/WriteTheChallengeOfTheOracle.pdf.