Size is one of those things that can be measured but is still very subjective. A child might think their teacher is tall, even though he’s only 5 feet 6 inches, while Manute Bol might think someone who stands 6’6: is short. The size of back yard cottages or laneway housing can determine their acceptance or rejection in single family neighborhoods—but, again, size is in the eye of the beholder.

Height, bulk, and scale of buildings can make or break a project or proposal. But, when does a building get too tall or too bulky? When does a house become a McMansion? What factor decides whether my neighbor and I can agree on a house that’s just right? What size is right depends on who you talk to.

So, to help us decide the right size for new housing options, the most important questions to ask focus on the outcomes we want—for families, neighborhoods, the environment.

There seems to be some consensus that backyard cottages are a good idea. In hours of discussion on laneway housing (called backyard cottages or detached accessory dwelling units—DADUs—in the US) in Vancouver and at the most recent hearing about it in Seattle, most of those who testified spoke in favor and cited affordability, flexibility as the main reasons cottages make sense. Cottages combine easy access for an aging family member with cost-savings, independence, and privacy, for example.

Portland has again demonstrated its progressive mindset in this area. Unlike Seattle, Portland has allowed detached accessory dwelling units for years in all parts of the city. Seattle, on the other hand, is proposing a rather modest 50 DADUs beginning sometime in the next year, in addition to the less than 2 dozen built under a pilot program started a few years ago.

Portland is also decoupling the size of the DADU from the size of the existing home. According to Eric Engstrom, Principal Planner at the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, this limitation would often require home owners to seek variances from the code because they could only build a DADU 1/3 the size of the existing house. This just isn’t big enough to make many projects worth doing. The Portland planning commission is considering a recommendation that would simply limit all DADUs to 800 square feet. Vancouver allows 750, and Seattle’s proposal is currently at 800 square feet as well.

But some Seattle city councilmembers expressed concerns about the size of cottages at the recent hearing. Sally Clark, the chair of the Council’s land use committee felt that the height, massing, and size of the cottages were bigger than anticipated, maybe too big. However, the Seattle planning commission has wisely recommended keeping the cottage proposal at 800 square feet and removing the limit on permits. So while Portland is moving toward bigger, Seattle is considering going smaller. Again, the subjective nature of size makes this a tricky political issue. Some neighbors wouldn’t be pleased with a cottage even it was Lilliputian. How can policy makers make find a middle ground?

One option would be to try and outsmart themselves by developing yet another seemingly objective formula of height bulk and scale like the one proposed by architect Seymour Auerbach, called the Bulk Factor. The Bulk Factor is an invention that Auerbach suggests would get around the problem of personal taste or fears of overbuilding. The Bulk Factor establish a ratio of volume to lot size to determine how big new buildings should be. This approach would establish the appropriate ratio based on a comparison with existing buildings. Auerbach’s Bulk Factor would create regulation based on the ratio to limit the size of DADUs. I think this would just lead to yet another formula, like the one Portland is dispensing with, that would stymie good projects.

How about a solution that is more performance-based, like the standard that Jason McLennan of the Cascadia Green Building Council suggests?

In the natural world, it is commonly understood that are limits to the density of any one species on a given area of land. These limits are never hard and fast rules, but are based on the carrying capacity of the land that varies through time and location. Too many of one animal in any one place results in less than ideal conditions for the whole. There are limits, but we believe our cleverness removes these rule on our behalf.

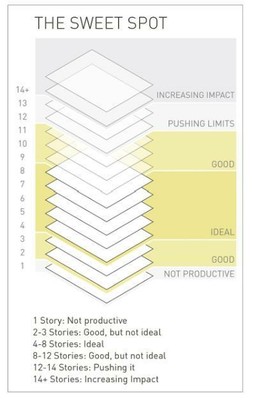

Now, McLennan is writing about the ‘sweet spot’ of mixed use buildings, which he places at 4 to 8 stories and densities of 30 to 100 dwelling units per acre.

McLennan’s excellent article, Density and Sustainability, is focused on a different type of development, but his point applies to cottages too. Building tall doesn’t automatically lead to sustainability. But McLennan’s fundamental performance-based question, “what building heights and urban densities result in the maximum benefits to culture, society and the environment?” is the right one to be asking when the size question comes up. True, culture, society and environment are pretty slippery terms, but a community could reach consensus on public benefits like access for families, and affordability. Hearing real people talk about the positive difference right sized backyard cottages would make for elderly family members or young families just starting out is convincing.

It is much easier for bureaucrats to administer a formula like the Bulk Factor. But looking for solutions that focus on outcomes makes more sense. One case study that is worth reading was put together by a team at Weber Thompson architects who created a site plan for Fairhaven Heights in Bellingham that all at once reduced the footprint of a proposed development, increased protections for critical areas, increased density and avoided height increases.

The newer proposal for Fairhaven Heights kept the same number of units, 739, and created a smaller foot print without increasing height. This was largely accomplished by reducing th

e number of detached single family units.

Size matters, but so does context. It’s our job to ask first what outcomes we want from rules governing land use.

Thanks to Joshua Curtis of the Seattle Great City Initiative and to Weber Thompson for background on Fairhaven Heights.

michael geller

I agree, size does matter when it comes to Laneway Housing. An interesting story in today’s Vancouver Sun suggests that in order to create more family rental housing in Vancouver, the maximum size of laneway units should be increased above 750 sq.ft. I do not agree, since I fear that this could increase community opposition. However, I do agree that a formula that relates the size of a laneway unit to the size of the existing house, and lot is worth exploring.

Joshua Curtis

Roger – Great post. I was at the Planning, Land Use, and Neighborhood Committee’s meeting yesterday and had the opportunity to listen in on the discussion about height limits. They were wavering between 23′ (the proposed height limit) and proposals to reduce it to 21’/22′ in order to prevent cottages that were overly imposing (both from the street and from neighbors’ back yards). I couldn’t help wondering if a 1′-2′ difference was really the right conversation, or if something like a bulk factor or another more performance-related solution would help with the issue. Overall, though, I am happy to see the city tackle this issue. It’s an important one. As a small aside, Seattle Great City Initiative is now simply “Great City”.

Beth

Over the past five years working as a green building designer in Portland I have found the ADU regulations irrational to the point that I know of few people who pursue building ADUs…legally. There are many issues, but basically it is legal to build an accessory structure not used for living (read: one with no stove) of much greater proportions, with many fewer design restrictions, and considerably fewer development fees than an ADU. The regulations on ADUs are restrictive to the point that adjustments of some kind seem necessary in most of the cases I’ve seen which adds expense, uncertainty, and time to the project. Smaller homes (600-1500 sf) are inherently much more resource efficient and often cover less of the lot and these are the homes that are penalized by the 33% rule that limits ADU size to a third of the house size. If the goal is to make quality housing situations for the US market, then I think 500 sf is a rough minimum (I’ve lived in Japan and other places where the acceptance of microhousing is greater). I am much more concerned with height and set back requirements as they impact privacy and solar access. I’m not a fan of ADUs above garages in the back third of lots for this reason (something that is currently allowable.) Also, the height of non-ADU accessory structures are tied to zoning which means that these can be two stories and more. Building an ADU is further complicated by the fact that there is no standard means of valuation for these structures and bank financing is difficult to nonexistent. These issues need to be addressed as well if ADUs are to be a viable strategy and policy. Small infill housing that is homeowner driven could be a great way of creating affordable, low impact housing. Ultimately I’d like to see some design charrettes with homeowners, designers, planners, developers, appraisers and financiers whereby they work together to create a form based code for ADUs in Portland.