Today’s Vancouver Sun gives some ink to a cluster of issues that I’ve been pondering of late: how BC’s carbon tax shift fits with Cap and Trade. I’m famously infatuated with carbon tax shifting. I’m also a zealot for auctioned Cap and Trade.

The good news is that with careful policy design, Cap and Tax can be better than either Cap or Tax. The Tax toughens the Cap, the way steel rebar strengthens concrete. The bad news is that without careful design, the two could weaken each other.

The challenge for policy makers is gaming—firms’ aptitude for subverting market rules established with good intentions. Remember how Enron and its ilk manipulated the California electricity market in 2001? The interaction of a carbon tax in British Columbia with a regionwide carbon Cap-and-Trade system in the West could open channels for such profiteering. In the worst case, gaming could both undermine and discredit the policies, risking their political survival. Fortunately, such gaming is preventable, as I’ll explain in a moment.

First, though, the upsides:

The pros of carbon taxes like British Columbia’s are their administrative ease and their certainty about price. The upside of auctioned Cap and Trade is its certainty about emissions reductions.

The difference between tax and cap is, in fact, small. Under a carbon tax, the government sets the price of carbon and the market determines the quantity emitted; in auctioned Cap and Trade, the government sets the quantity of carbon emitted and the market sets the price. A tax is a sort of variable cap, and an auctioned cap is a sort of variable tax.

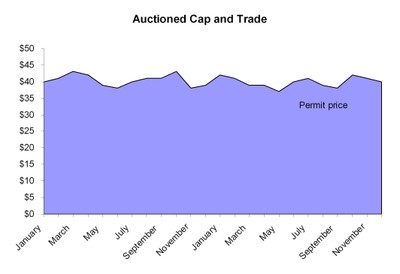

Moreover, Cap and Tax readily blend and hybridize. Imagine this case: To reduce emissions by 2 percent in a certain year, let’s say that the price must rise to $40 per ton of carbon dioxide emitted. Under an auctioned Cap-and-Trade system that targets a 2 percent reduction, permits will sell for $40 on average. Here’s a chart of one possible outcome, with the price of auctioned emissions permits varying around that price.

Imagine the same case, but this time assume we first levy a tax of $30 per ton of carbon dioxide. The market price of permits (whether at auction or in after-auction trading) will average $10. Notice: carbon emissions bring the same total price of $40 per ton, which keeps emissions under the cap. But three-quarters of the proceeds are now collected by the tax. The remainder will be collected through the auction. Here’s a chart of one possible outcome.

Why bother with a tax at all? Because the auctioned price might vary more widely, as in this chart, where permit prices swing from high to low. When the prices are high, everyone will pay attention to their emissions; when prices drop, so will attention. The variability of prices could weaken the incentive to invest in efficiency and renewables. (With good auction design that allows many participants to bid on permits and allows them to “bank” or stockpile permits in low-price times for use in high-price times, such price gyrations are unlikely. But they’re possible.) Here’s one possible outcome.

A carbon tax, shown below, puts a floor under the price of carbon and tells everyone in advance what that floor will be. It ensures that our attention won’t stray, that the incentive for clean energy remains strong.

In fact, there’s a way to build a carbon tax right into a Cap-and-Trade auction, eliminating administrative duplication. It is to set a minimum bid, or “reserve price,” for permits. As Ebay users know, nothing gets sold unless its reserve price is met. If we set a reserve price of $30 per one-ton permit, we’ve effectively implemented a $30/ton carbon tax.

That’s the updside of Cap + Tax. The downside is the risk of gaming. It comes in at the geographic boundaries of the states and provinces. The tax applies only in British Columbia at present (and I’m not optimistic about others emulating soon). (Quebec also has a carbon tax, but it’s minuscule.) The Cap-and-Trade system will span seven states and three provinces. That mismatch creates challenges.

Well, actually, a promise that the province made its businesses creates the challenge. BC’s Minister of Finance promised BC firms that they won’t get dinged twice by carbon pricing. That is, they won’t pay both for Cap-and-Trade permits and the carbon tax. Or, more specifically: the sum of carbon taxes and carbon permit prices will not exceed what their WCI competitors pay for carbon permits alone.

BC’s commitment makes some sense. If the Cap and the Tax cover the same fossil fuels and sectors of the economy, double-charging BC firms for emissions wouldn’t reduce emissions by extra amounts. Or, rather, it would diminish emissions in the province, but it would not trim emissions overall. Under a regional Cap, the more any one jurisdiction reduces emissions, the less every other jurisdiction needs to reduce emissions. So BC’s carbon tax might relocate emissions reductions into the province, whether or not that’s the least expensive place to make them. Of course, it will bring money into the province too, because taxed BC firms won’t be buying as many permits, which will leave them on the auction block for non-BC firms.

Because WCI has yet to decide what form of Cap and Trade to adopt and what climate pollution sources to cover with it, the possible ways it might interact with BC’s carbon tax shift are too numerous to explain in less than a book.

Instead, I’ll just illustrate the kinds of pitfalls along the path to Cap + Tax.

Can’t British Columbia give its firms carbon-tax credit for whatever they spend buying carbon permits? That way, BC firms only get dinged once.

Maybe, but it’s tricky. Say you’re a financial services company in British Columbia. You decide to get into the carbon-permit brokering business; you buy permits and supply them on demand to your clients in the fossil-fuels industry. You realize quickly that as long as the price of permits (imagine it’s $15/ton on the WCI market) is below the carbon tax rate (which will rise to $30/ton in 2012), your clients don’t care what

price they pay for permits. That is, they have to pay the carbon-tax rate anyway, so they’re completely indifferent to prices below $30 a ton. What do you do? You might offer them other, unrelated business and financial services for free—pension fund management, cash management, employee training, golf junkets—as long as they buy permits from you at $30 a ton. You make huge profits, and your clients get sweet perks, too. Who pays? British Columbians: the BC Treasury has already rebated these expected funds to BC firms and households through income tax reductions.

The Treasury might be able to prevent such tax avoidance with the right kinds of auditing practices, and the price of permits might never fall below the tax rate. But why run the risk? Several WCI participants, fearful of such financial chicanery, argue that the carbon market should be limited to energy companies—those who actually bring fossil fuels into the region. But who’s to say energy companies wouldn’t do the same things? Enron, after all, was an energy company. Besides, other gaming and tax avoidance scenarios present themselves within the energy sector, such as complicated transactions between holding companies and subsidiaries or between spinoffs and parent companies that share stockholders.

Anticipating all the possible gaming and tax avoidance strategies that business might invent, devising countermeasures, and testing those countermeasures for new loopholes, is an exercise in infinite regression. Instead, I’ll list some likely solutions, in roughly declining order of preference.

1. Set a Regionwide Price Floor.

BC’s carbon tax shift sets a new standard for all WCI states and provinces. It covers all fossil fuels without exception. It puts a floor under the cost of pollution. It rebates all its proceeds to BC families and businesses through tax rate reductions. It gives climate dividends to low-income families to buffer them from the unfairness of climate change. And it makes prices tell the truth about climate.

By matching those accomplishments, the Western Climate Initiative can close off avenues to gaming. In short, WCI can design a comprehensive, auctioned Cap-and-Trade system with fairness buffers built in and with a minimum carbon price set regionwide. Just as Ebay sellers set a “reserve price” below which they will not sell their items, WCI states and provinces can set a reserve price that matches or exceeds BC’s carbon tax rate. Such a provision would essentially universalize BC’s carbon tax shift, raising the playing field across the West and sealing off the back channels that could otherwise lead to gaming, scandal, and political backlash. If WCI adopts a reserve price, British Columbia could integrate its carbon tax into the auctioned Cap-and-Trade system. That is, it could convert its tax into a reserve price in its provincial carbon permit auction; it could stop collecting its tax separately because the permit auction would generate the same revenue and more.

2. Double Ding.

BC could revoke its assurances against “double-dinging” BC businesses and let them pay both the tax and also the price of permits at auction. This action would cost BC firms something, but it would secure the integrity of the Cap-and-Trade system. In the grand scheme of things, BC’s carbon tax is not high enough to have large impacts on the competitiveness of BC firms. If anything, it will push them into leadership positions in their industries by stimulating innovation and smart energy choices. Remember, the BC carbon tax shift returns every dollar of pollution tax revenue to businesses as corporate tax reductions and to families as income tax reductions. On balance, BC’s economy will probably benefit: spending on imported fuels will diminish; spending on local goods will increase.

Even if WCI were to go astray and distribute permits for free, the carbon tax would actually recoup some of the windfall profits that BC firms would otherwise receive.

3. Set a price floor in British Columbia.

The province could convert its carbon tax into a reserve price in its own permit auction, in all sectors of the economy that WCI caps. This strategy would only work if BC firms are required to buy permits from a BC-only auction. Once all BC permits are sold for an auction period, BC firms would be free to purchase permits from other WCI jurisdictions that have no reserve price. In this way, permits are still tradable throughout the region, but British Columbia protects its carbon tax. Enforcing the rule that BC firms must buy BC permits first would take some attention. What would stop some BC firms from waiting out the BC auction in hopes of getting cheaper permits after its peers have bought up all BC’s own permits? Still, I think this approach could work.

4. Give permits to carbon tax payers.

Rather than auctioning all its permits, British Columbia could hold some permits and distribute them to BC firms in proportion to the carbon taxes they pay.

This strategy would safeguard the public’s revenue, and it’s apparently under consideration in Victoria. A recent Vancouver Sun article notes:

“Large-scale emitters—pulp mills, refineries, cement plants and the like—will have to operate within a cap, purchase credits or pay a penalty. But the government has pledged to avoid double counting, so carbon taxes will have to be credited within the carbon trading system.”

The province could calculate the number of credits to give for each $100 of carbon tax payment based on the average price at the last auction. It could estimate how many permits to auction and how many to hold back in anticipation of future tax payments based on recent energy consumption trends. If the province runs out of credits to distribute to tax payers it can buy permits from outside British Columbia to fill the deficit. If it holds back too many, it can sell them in the next auction period.

5. Untax capped sectors.

If a sector of the economy such as transportation fuels is covered by WCI’s auctioned, regional Cap-and-Trade system, the province could exempt it from the tax. This way, BC businesses won’t pay twice and uncapped sectors will still pay the carbon tax. Double dinging and gaming both go away.

Of course, administering this approach may require some problem solving: if the tax applies at the refinery gate and the cap applies down the supply chain at the fuel “rack,” for example, the BC Treasury will need to devise methods for refunding carbon taxes that are already factored in fuel prices. Again, such problems have reasonable solutions, but they’re not always clean and elegant.

Cap and Tax can be better than Cap or Tax, as long as it’s carefully designed. This is good news for the climate, British Columbia, and the Western Climate Initiative. It’s also good news for me: I don’t have to choose between my infatuation with tax shifting and my zealotry for auctioned Cap and Trade.

john nash

I appreciate the concepts for “cap and trade” and for “tax and dividend”. Where it gets messy for me is when tax policy is introduced via tax rebates or the use of earned income credits. I see the use of tax credits for types of vehicles as a means of making the particular “chosen” vehicle to be the one the public should buy. Tax policy is a wonderful thing, but it offers incentives that may not offer an individual the best solution to their situation. Make the actaul cost the determining factor and the best solutions will rise to the top.So why not just add a “fee” or “carbon contribution” to every btu of energy used, and then give it back to the each and every citizen equally. The fee would begin small, but have scheduled increases over time. Everyone can plan for the future; manufacturers, individuals, mass transit systems, car companies……. We could even place the same btu tax on all imported items; the btu’s to ship to us and the btu’s to produce the items. It quite simply would have everyone with skin in the game. Those big svv’ will be passed down to the poor. But now those vehicles are worth a whole lot less because of their increased operating costs; lower trade-in value means a lower re-sale price on the open market. Yes they will be more expensive to re-fuel, but because they are newer vehicles they will have lower maintenance costs associated with ownership. Landlords will have a profit motive too, I am one by the way, to make their apartments more fuel efficient by allowing me to make improvements and charging higher rent. It puts the costs and benefits at everyones finger tips. On every receipt you will see your contribution to the system and every month you will recieve your equal portion of the benefits. Every day you shop, buy gas, pay an electric bill, turn the heat up or down, plant a tree to shade your home, buy an appliance….. nothing and no one will be exempt. Some will not take advantage by turning their heat down or insulate their attic, my guess is that the vast majority will. The race to utilizing energy that produces no co2 will be on. Industry will now have a natural market to produce and the consumers will be clamoring for it! Just my thoughts.

Clark Williams-Derry

Hey there! Good thoughts.I generally agree! The most straightforward climate policy would be to put a price on all quantifiable GHG emissions, and rebate all money collected directly to people on a per-capita basis. Then we could just get out of the way, and let the market decide the optimal mix of emissions reductions; and the rebate would help alleviate the economic impact on the poor and middle class. (And then I could relax and get a new job, or at least a new set of obsessions!)I’d prefer that the price be set via a firm cap and a carbon auction. Three reasons. First, a cap guarantees that we reach our emissions targets: as long as the cap was well-enforced, we’d know exactly how much carbon was entering the atmosphere from the capped sectors. Second, if carbon emissions were capped and politicians ever decided to ease carbon prices, they’d have to do it in a transparent & public way: by breaking the carbon cap by a specficied amount. The public would see the choice clearly. With a tax, on the other hand, politicians could ease the tax & the public would never quite know how much extra carbon was emitted as a result. Third, I think it’s possible that a cap would provide greater energy price stability than a tax. With a tax, the amount of the tax is a given, but energy prices vary with the market. With a cap, energy prices could vary, but (in theory at least) the total cost of energy + carbon could remain somewhat stable. (I’m not convinced that things will work out this way—and the European system may offer counteraxamples.)That said, I’d also be quite content with a carbon tax, as long as I was convinced that it would be stiff enough to do the job over the long term. There are other reasons to favor a carbon tax as well—simplicity, revenue stability, etc. They’re good reasons, but I prefer the certainty of a cap.However, as with all things, I don’t get to set the policy. I wish I did, but I don’t. And there’s reason to believe that “tax and dividend” and “cap and dividend” won’t fly in some jurisdictions. First, there are legal problems with the “dividend” approach in some jurisdictions. For example, the current interpretation of the Washington state constitution sets up some barriers against distributing public funds to people who aren’t “poor and infirm.” Second, there are lots of people who don’t favor the “dividend” approach. I generally do—though I could also be convinced that other sorts of spending would also keep the system fair and efficient—but lots of folks disagree. So, because I don’t get the option of setting policy myself, I think it should be Sightline’s role to point to a number of different ways that a climate policy can be effective, efficient, and fair. Some of those mechanisms won’t be my top choice. Some won’t even be close. But I’d rather offer a bunch of feasible options for policymakers to choose from—based on legal necessity and political reality—than stick with the one perfect solution that I think makes the most sense.That doesn’t mean I’ll abandon my advocacy for a dividend approach, though.