This is part three of a series. Here are parts one and two.

I’m taking a look at a Seattle Timesarticle about a study claiming that regulation has added $200,000 to Seattle home prices. I was skeptical, so I ran the numbers on trends in other cities. It turns out that the numbers tend to give lie to claims that growth management is to blame for unaffordable housing.

In our last installment, the article was using housing bubble appreciation from 2001 to 2006 to imply that growth management makes housing unaffordable in Seattle. Unfortunately for that line of thinking, Seattle’s price increases are pretty modest by national standards. In fact, official US figures (pdf) don’t have Seattle anywhere near the top of cities for appreciation from 2001 to 2006. Where prices spiked was in the Sunbelt, a region notorious for its near total lack of meaningful growth controls. Florida had by far the largest number of super-appreciating cities with a handful of showings by cities in Arizona, Idaho, and California. So what gives? (Could it be lack of regulation causes unaffordable housing?)

The thing is, Seattle housing prices just haven’t appreciated that much by national standards. That’s what the official US government figures show. By 2006, the Seattle metro area ranked in exactly 57th nationally for one-year housing price appreciation. That’s right, 57th. Tacoma, sitting in compartively growth management-lax Pierce County, ranked 49th. Over the 5 year period from 2001 to 2006, Seattle’s rate of appreciation was outstripped by scores of cities from all points of the compass, often by multiples of two or three or even more. (2/15: I did some updating to this para.)

In fact, Seattle’s appreciation was slower than the national average. Again, using offiical federal numbers, by 2006, total US housing prices had increased 293 percent since 1980, and 57 percent since 2001. Comparable figures since 1980 aren’t available for Seattle, but our appreciation was 54.5 percent from 2001 to 2006.

But what about over the longer term? After all, Eicher’s analysis is for a 17 year period.

Well, according to Standard & Poor’s Home Pricing Indices, Seattle has had modest long term housing price increases. According to the S&P ranking of the big city appreciation from 1990 to 2006, Seattle comes in 11th out of the 18 cities with comparable data. Where did housing prices rise faster? In order: Miami, Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, Las Vegas, Washington DC, Tampa, San Franciso, New York, and Portland. (Portland and Seattle appreciated at similarly modest rates over the period.) Minneapolis and Boston are right in there too.

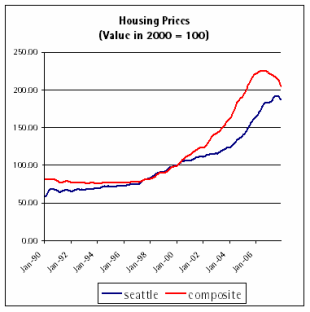

Take a look at the chart. It shows big city price changes since 1990. Washington’s Growth Management Act became operational in the mid-1990s. Notice anything?

Yeah, me too. It looks like after Seattle starting operating under growth management, our housing price increases actually started lagging the national increase. Correlation ain’t causality and all that, but the numbers make it kind of difficult to believe that the burden of growth management (or any other regulation for that matter) is out of whack in Seattle.

Okay look, I don’t want to spend too much time criticizing the principal research Theo Eicher. The reporting was so bad that it’s hard to know if his views were represented accurately. But the article raises more than a few red flags.

Maybe it is true that regulation is the cause of almost all of Seattle’s price increase. And maybe growth management is the prime culprit. Maybe without regulation Seattle’s median housing price would be around $250,000, roughly the price of a house in Provo, Utah.

Maybe.

On the other hand, the numbers suggest to me that Seattle might be under-regulated, compared to other US cities.

I’m going to start digging into the study now. And, yes, I’ll post again if I find anything interesting.

BC

Excellent research, and just as relevant to anti-sprawl policies down here in Portland too. So… are you, or is anyone else, preparing a response to be published in the Times? Please keep us posted.

David Hiller

Eric:Among the millions of questions I asked myself about this drivel was, how does this reporter completely miss skyrocketing commodity prices (lumber, steel, concrete) and steep but relatively slower growth in labor prices in buying this schlock? How does her editor or fact-checker miss it?At 3% annual growth, building materials for new construction would have nearly doubled in the time period in question. The most unethical reporting I’ve seen come out of the Times in some time – and another embarrasment for UoW to be affiliated with the “study’s” author.

Eric de Place

EXCELLENT points, David. Construction costs have increased far beyond reported standard inflation. Believe it or not, there’s probably going to be a fourth installment here—I just love ranting—that will be more specific to the study, and not the article. I’ll try to weave some of the inflation stuff in if I can.

danlewis4545

Eric:Nice overview and analysis. I agree with a lot of it. One correction, and one comment.1. In part 3 you reference government data showing that, “By 2006, the Seattle metro area ranked in exactly 57th nationally for annual housing price appreciation (over the period from 2001 to 2006). That’s right, 57th. Tacoma, sitting in compartively growth management-lax Pierce County, ranked 49th.”This ranking was not based on the period from 2001 to 2006… it was based only on one-year appreciation.The link you posted was http://www.ofheo.gov/media/pdf/1q06hpi.pdf, and the ranking on page 29.This doesn’t make a huge difference, but its important since you mentioned the timing of Seattle’s appreciation.2. I live in San Francisco, which also has experienced high appreciation. This is partly due to the protection of lands around San Francisco, but few to no people suggest that we develop the Marin Headlands. Even people who can’t afford a house.What does make prices higher is price-control regulation. Ironic, isn’t it? Because rent’s are price controlled, a huge portion of the population pays way under market (e.g., $700 / month for a $4000 / month apartment). This means that the owners need to make up the difference by charging more to those who are starting new leases.Also, because property taxes are locked for homes (unless sold), people have less of an incentive to ever sell, which lowers supply for new buyers, and raises prices. While house values have appreciated 5-10x over the past decade, the taxes on the properties didn’t go up. This hurts the local economy for everyone, while the home-owner makes out like a bandit on both ends.Please don’t allow price controls and property tax controls to start in Seattle.

Michael P Stein

I commend you for recognizing that you certainly do need to look at the actual study rather than the newspaper summary (caricature?) of it. My guess is that Eicher really was including zoning in his list of regulations that increase cost, since he attributed $100K of price increase elsewhere to regulation. It’s important to note that simply comparing price increases in Seattle vs. the Sunbelt is not adequate evidence that Eicher is wrong. If the Sunbelt had higher population growth then one would need to seek alternative explanations for at least some of Seattle’s price rise. Regulatory suppression of supply is only one of a number of factors that could be at work. E.g., terrain features can mean that within the same number of square miles, city A has less land that is cost-effective to develop than city B even if they are otherwise identical in demographics and regulatory burden.There are a lot of ways in which Eicher could have gone wrong; the first thing I would look at is how he handles the fact that the size of the average house has grown over the years. Because most people’s demand curve for housing seems to be based on the monthly mortgage payment rather than the nominal cash price, low rates and easy mortgage terms have turned renters into buyers and owners of smaller homes into buyers of bigger homes.

Eric de Place

danlewis4545,Thanks for the correction. I’m fixing the post now.

Dan

My guess is that Eicher really was including zoning in his list of regulations that increase cost, since he attributed $100K of price increase elsewhere to regulationTable 4c gets at this. Only some of this is zoning (but it doesn’t differentiate between zoning that is demanded by the community and zoning imposed by state growth regulation – Eicher doesn’t reference the standard statewide growth management literature so we must look askance at his variables). The majority of the rest are things like impact fees – fees imposed on the…erm…impacts of growth (often enacted in the absence of raising taxes to pay for growth).Eicher also doesn’t use any amenity or hedonic factors in the explanatory variables for price increases. This alone makes the paper suspect. Not sure what he was trying to say, but a glance at his CV shows he’s a macro guy so he’s missing the sublety of why prices rise.

Finish

Thank you. That’s all, just thank you.

Arie v.

There are some great arguments here, not the least is which I don’t think anyone wants Seattle to become Houston…However if you read the comments in the Times to the article the comments in the Times to the article there is a lot of pain and anecdotal support for regulations that are inefficient or unreasonable. Building my own home I can tally thousands of dollars spent wisely on regulation (small examples being silt fence, drainage and topsoil retention rules) and as much that I would classify as bureaucratic waste such as the many month long waits for permits, critical areas designations, etc. My point is that it is dangerous to defend regulation without also acknowledging there are areas where we can and must do better, especially where housing affordability is impacted.

Arie v.

Cut and paste error above. Here is the right link to the comments to the Times article.

keen

Maybe it’s just the way I’m reading Eicher’s paper after reading the times article.(See http://depts.washington.edu/teclass/landuse/Seattle.pdf)But it seems to me that in the beginning of the text he wants us to believe that ‘parks and green spaces’ cause a big part of this $200k price increase.But, later in the text he just credits ‘overregulation’. Looking at table 2 it looks like there are a lot (as in 82) local policies that come together to make the price increase.He then cites 16 policies that make seattle different (and I presume are the key drivers of the $200k? what exactly about these makes the price go up?)–for a description of these see the wharton indexstate legislature involvement in regulationstate courts involvement in regulationApproval Delaypermit lag for rezoning, >50 sf units, mths-midpointpermit lag for subdivision appr (norezoning), >50 sf units, mths-midpointreview time for single family units (months)permit lag for rezoning, mf project, mths-midpointpermit lag for subdivision appr (norezoning), mf project, mths-midpointreview time for multi family units (months)Local Political Pressurecommunity pressure involvement in regulationdesign review board approval required (norezoning)environ review board approval required (norezoning)

Dan

in the beginning of the text he wants us to believe that ‘parks and green spaces’ cause a big part of this $200k price increase. They do.From a macro perspective, they lessen the supply of land. From a microecon perspective, they provide desired amenities that people seek out and pay for (proximate principle, and this shows up in assessor records).Eicher is a macro guy, so he’s not going to mention things like good job growth, amenities such as natural beauty, literacy rate, proximity to UW-Microsoft-Amazon as reasons for people with money to move to Seattle and bid up rents. Absolutely regulation drives up prices. Some of it is designed to (and Eicher shows this in table 4c, impact fees). Some regulation has a consequence of driving up prices. What the anti-regulation folks don’t mention is what will happen if regulation goes away (it won’t because of the protection, bit they wish really hard it would) – chaos. Then there will be no certainty in investment.

Rob Harrison AIA

Not to be contrary here, but setting aside the increases due to procedural road-blocks, is it possible that at least some of the increases in the cost of housing indicate that regulation is working? That is, because of regulation our houses are more desirable and thus more valuable? There are at least some benefits: People who already own homes have enjoyed unprecedented growth of equity, which does make it possible for them to renovate and stay where they are.

dave

Isn’t it strange we are concerned growth management policies might increase house values, yet the entire nation is currently lamenting the current decline in house values? Which is it we want? Do we want house values to climb or do we want to keep them low? Is it rationale to want it both ways?The fact is that all the costs of urban growth are paid by us – either in the price of the house or in all the externalized costs paid indirectly by the residents of the city. So even if growth management policies raise the price of a new house, they are reducing the externalized costs that someone struggling to buy a house would have to pay over the long haul. Most growth management policies better connect the costs of growth with the behavior. Widespread, indiscriminate new-house subsidies via externalization of costs is a very inefficient way to address housing affordability for those at or below poverty level. They can’t afford even a cheap new house anyway. And all those renters can’t afford the externalized costs of the subsidies.Dave GardnerProducer/DirectorHooked on Growth: Our Misguided Quest for Prosperityhttp://www.growthbusters.com